Early on in this book the author describes Taiwan as a “heterotopia.” A topia is a place, so a utopia is a perfect one and a distopia is a less-than-ideal one. A heterotopia is somewhere that’s different from what you know — different food, different popular music, maybe even a different language.

Michel Foucault, who invented the term, gave prisons and brothels as examples of heterotopias, but Taiwan is certainly not like either of these. But to tourists arriving from China it is both different and familiar, with its 101 Building, high-speed railways and highly educated population. Even the script used is different from what is used in China, though the spoken language is immediately recognizable.

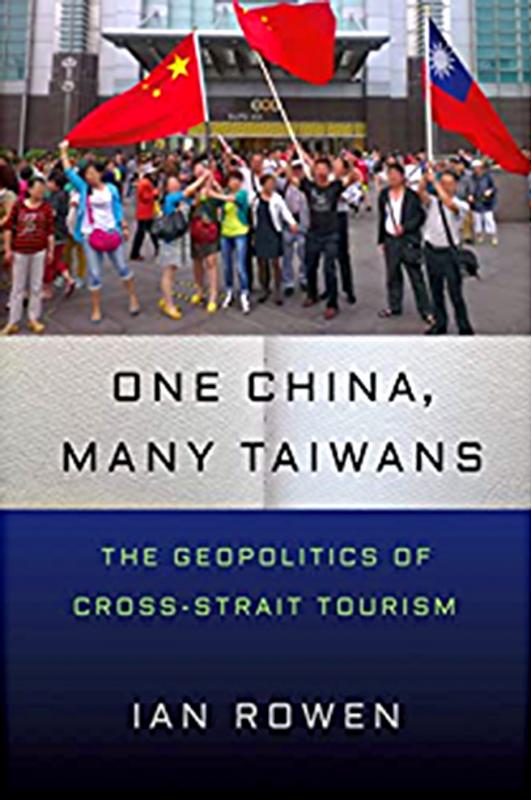

Cross-strait tourism started under the presidency of Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). Ma, apart from his stance as by-and-large pro-China, hoped that the tourists would return home with a positive view of, say, Taiwanese democracy. This book examines the actual results in detail. According to academic Ian Rowen, tourism deepened the differences.

Beginning in 2008, the authorities in Beijing predictably hoped its cross-strait tourists would see Taiwan as part of China in almost every way. The Taiwanese expected the opposite.

Taiwan had, of course, experienced a large-scale influx of Chinese fully intending this time to stay. The late 1940s was when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) pioneered a large movement of KMT supporters to Taiwan fleeing the advancing Communists.

One China, Many Taiwans comes from Cornell University Press. It also has a reputation for being strong on Asian studies. The campus is at Ithaka, named after the home Homer’s Ulysses found it so hard to reach.

The book covers many different aspects — tour groups versus individual travellers, and so on. I’d been under the impression the Chinese authorities didn’t allow the latter but I was clearly mistaken as Rowen interviews many of them.

The fact is that both sides believed they were motivated by the same impulse whereas in fact their intentions were almost opposite. But these opposites interlocked in such a way that both sides believed their view to be paramount.

A typical 8-day tour is described — Shilin Night Market, the 101 Building, the National Palace Museum, Sun Moon Lake and Kaohsiung. Reactions were usually of the kind of “small and fresh, with still some remnants of the Japanese era.” Taiwanese pop music was typically viewed as “petit bourgeois.”

“Taiwan was colonized by Japan? Really? Are you sure? Why didn’t I know about that?” said one visitor. Another thought Taiwan was “almost like I imagined Hawaii to be.”

Others saw Taiwan as exemplifying the warmth and friendliness of a China of old, while retaining its similarity to Japan. Japan is highly regarded in China these days, we are told.

Many tourists were keen to give their views, without it being clear whether they were members of a tour group or not.

As for Taiwan’s democracy, some saw it as “a sham” while others praised the elections without seeing them as contradicting the island’s “essential Chineseness.”

Many individual tourists came to witness Taiwan’s pop music scene, Kenting’s Spring Scream and so on. Others hoped to visit relatives who had moved to Taiwan earlier.

There’s plenty more. There is the fatal coach crash of July 18, 2016, with its drunk driver and locked bus doors.

The 2020 crisis in Hong Kong over the National Security Law was followed by the biggest DPP electoral victory of all time. COVID-19 quickly complicated the situation, with Taiwan’s response world-leading. Even so, global tourism had almost totally shut down.

This excellent book shows some of the complexities of Chinese tourism to Taiwan. The title, incidentally, echoes the old political shuttlecock, One China, Two Systems.

The author’s conclusion is that “beyond Taiwan and China, in other regions ... [with] rising tides and changes in climates,” tourism’s impact will effect a change in the global balance overall.

It is an old axiom that everyone wants to travel but nobody wants to be labeled as a tourist. This hasn’t prevented millions on every continent at least behaving like tourists. Nevertheless, Taiwan and China are undoubtedly special cases. To begin with, they are simultaneously no different and very different indeed. Language unites them, but writing divides them. Their governments’ claims, too, set them apart, yet their histories overlap, both in the distant past and more recently.

Yet few from the UK would think that the fact it once ruled northern France is a reason for treating it as a special travel destination today.

Furthermore, China and Taiwan are at odds in so many ways, yet are very close neighbors, with a language in common and many Taiwanese businessmen relocating to, say, Shanghai on a semi-permanent basis.

The book contains an interesting anecdote concerning Taiwanese citizens’ problems when traveling internationally. The author narrates it as follows.

“‘Taiwan is not a country. Please present an identity document from a country recognized by the UN.’ So said an officer at the entrance to the Geneva headquarters of the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights to a Taiwanese student in 2017. Before arriving in Switzerland the student’s professor had successfully [applied] for herself and her team of students to enter the office’s public gallery. However, each of the team had been treated differently when they presented their passports to the various staff at the office’s registration counter. The professor’s passport was rejected, but she was allowed to enter after presenting her international driver’s license.”

Another student was initially allowed to enter after presenting his international driver’s card, but he was later ejected after another “very rude” staffer (in the words of the professor) had rejected the same card from another student.

This was especially shocking coming from an official of an organization specifically dedicated to the promotion of human rights.

This book, published earlier this year, obviously didn’t incorporate the current escalation in war-games in the Taiwan Strait. Things can only improve, one feels, but nevertheless they may not.

Rowen’s writing is characterized by clarity and a total lack of the ideological jargon that spoils so many books in the humanities these days.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern