Even among the diverse gathering at the Liberty Square arch, Glib Ivanov stands out. At 192cm, the 24-year-old Odesa native towers above the crowd, accentuated by his floppy mop of hair.

It’s an appropriately blustery February afternoon when I first meet Ivanov — a doctoral researcher working on floating offshore wind turbines — at an event to mark the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Just like his appearance, his opinions mark him out.

“I think everyone should tell the truth: Many Russian-speaking Ukrainians, including some of my family, initially hoped the invasion would just replace Zelensky, who was not then popular,” he says. “But once we realized the Russians were just here to kill people, it changed.”

Photo: James Baron

Ivanov is here to show solidarity with his compatriots. He is also keen to emphasize the opportunities for cooperation between Taiwan and Ukraine through his work National Taiwan University (NTU).

Detecting my accent, Ivanov praises the UK’s achievements in renewables.

“The government invested more than 30 million pounds in floating wind,” he says, referring to the Kincardine floating wind turbine farm off the coast of Aberdeen in Scotland. “The technology is from an American company — Principle Power — but they couldn’t get funding because no one cares about green energy in the US!”

Photo courtesy of Glib Ivanov

Instead, he says, the company looked abroad. In addition to the UK, there is also a farm in Portugal, where a subsidiary of the company operates. Other European countries have also expressed interest.

Citing limited space for onshore turbines and concerns over their proximity to residential areas, Ivanov says floating wind turbine technology is ideal for Taiwan. Protests such as those seen in 2013 against the construction of a wind farm at Yuanli (苑裡) in Miaoli County by German company InfraVest GmbH are legitimate, Ivanov believes. “No one really knows how far the turbines could fly if a typhoon breaks them, so it really might not be that safe.”

LONG-TERM PLANS

Photo: James Baron

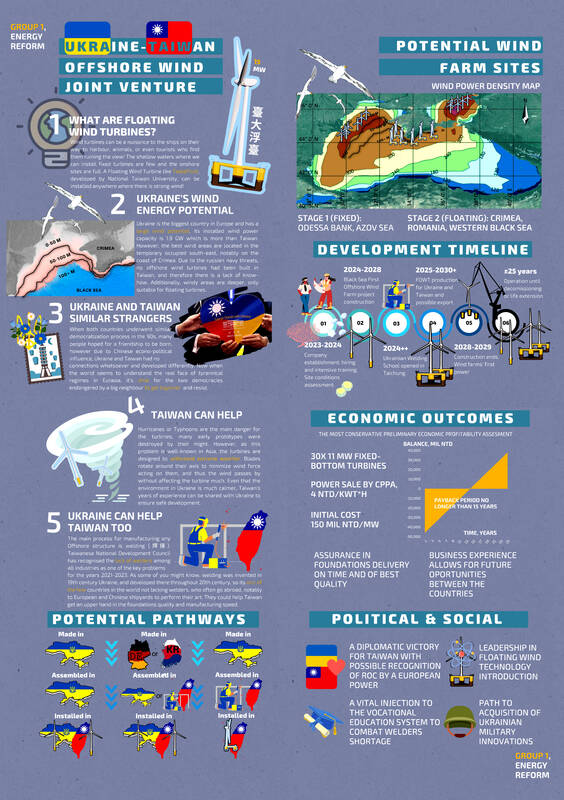

While regular offshore projects are ongoing, Ivanov says the construction of “Eiffel Tower”-sized foundations required for fixed turbines in deeper waters is prohibitively expensive, making floating offshore wind turbines a possible alternative. While the immediate goal is to bring benefit to Taiwan, Ivanov sees this as a “side project” to broader, long-term cooperation between Ukraine and Taiwan.

“Together, they could outperform the UK,” he says.

A few weeks later, I visit Ivanov at the Department of Engineering Science and Ocean Engineering at the eastern end of the NTU campus. While not quite the “rat-infested building” Ivanov had jokingly described, it’s not glamorous.

Waiting at the main entrance, Ivanov is again snappily dressed, this time in a more formal blue blazer. “High-tech, smart performance fabric,” he says. “Expensive, but a necessity for business trips in this climate — keeps the cool in and wrinkles out. I’ve yet to put it to the test, though.”

BLEND OF CULTURES

Upon entering, we’re greeted by a model of his floating turbine design. He points out the various components and functions, before guiding me past workshops and a study room with a sign reading “The Chamber” in Gothic lettering. Upstairs, in the comfortably furnished Energy Research Center, Ivanov serves tea.

Ivanov outlines his team’s plans for a joint industry project managed by the government-owned Ship and Ocean Industries R&D Center (SOIC), with support from NTU, National Taiwan Ocean University and CSBC Corporation, owner of the world’s largest dry dock in Kaohsiung. The aim is to secure US$25 million in investment from companies who will then have the “preferential right” to develop floating wind turbine farms.

“But how is this is connected with Ukraine?” he asks rhetorically. “Well, before the war, there were twice as many wind turbines in Ukraine as Taiwan. The wind sector was pretty developed.”

Unfortunately, says Ivanov, a third of these were in Crimea and suspended operations after the 2014 occupation of the region. With Russia under sanctions and unwilling to pay for upkeep, hundreds of turbines fell into disrepair.

Fears of Russian naval aggression had made the floating turbines unappealing, but things changed with the sinking of the Moskva, the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s flagship in April 2022. This was the vessel that had demanded the surrender of Ukrainian border guards on Snake Island on the first day of the war, only to be met with the infamous riposte “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.”

Ivanov chuckles gleefully as he utters the invective. “So now, the fear is gone,” he says. “And the Ukrainian government has committed to renewable energy after the war.”

EXPLORING THE PATHWAYS

Ivanov hopes to pair Taiwanese engineering and floating wind turbine know-how with Ukrainian fabrication skills. He unfurls a poster to illustrate possible pathways to this. Highlighting a dearth of qualified welders in Taiwan, Ivanov believes Ukrainian expertise, which China has historically tapped, can be leveraged here. Among the proposals is the establishment of a Ukrainian-led welding school in Taichung to train local talent.

On the other side of this joint venture, would be investment in floating wind turbines in the Black Sea, using the expertise gained on projects in Taiwan. With support for Taiwan burgeoning in Central and Eastern Europe, the incentives might extend beyond economic rewards. While Ivanov’s hopes for recognition of Taiwan by Kyiv might be fanciful, professional, academic and civil society exchanges could benefit. He uses his own case as an example.

“As a PhD student, I’m exempt from conscription,” he says. “But because Ukraine doesn’t recognize Taiwanese documents, I’m considered to be evading. If we had projects generating huge earnings, it would give a punch to the government to do something.”

Having recently taken up a role at SOIC working on assessment and promotion of joint industry projects, Ivanov hopes to play a part in delivering this wake-up call. And, whatever form cooperation takes, he is not looking for charity. “As a Ukrainian, I don’t want it to be just rich Taiwan helping poor Ukraine. After the war, it should be a partnership of equals,” he says.

A jumbo operation is moving 20 elephants across the breadth of India to the mammoth private zoo set up by the son of Asia’s richest man, adjoining a sprawling oil refinery. The elephants have been “freed from the exploitative logging industry,” according to the Vantara Animal Rescue Centre, run by Anant Ambani, son of the billionaire head of Reliance Industries Mukesh Ambani, a close ally of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The sheer scale of the self-declared “world’s biggest wild animal rescue center” has raised eyebrows — including more than 50 bears, 160 tigers, 200 lions, 250 leopards and 900 crocodiles, according to

They were four years old, 15 or only seven months when they were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald and Ravensbruck. Some were born there. Somehow they survived, began their lives again and had children, grandchildren and even great grandchildren themselves. Now in the evening of their lives, some 40 survivors of the Nazi camps tell their story as the world marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most notorious of the death camps. In 15 countries, from Israel to Poland, Russia to Argentina, Canada to South Africa, they spoke of victory over absolute evil. Some spoke publicly for the first