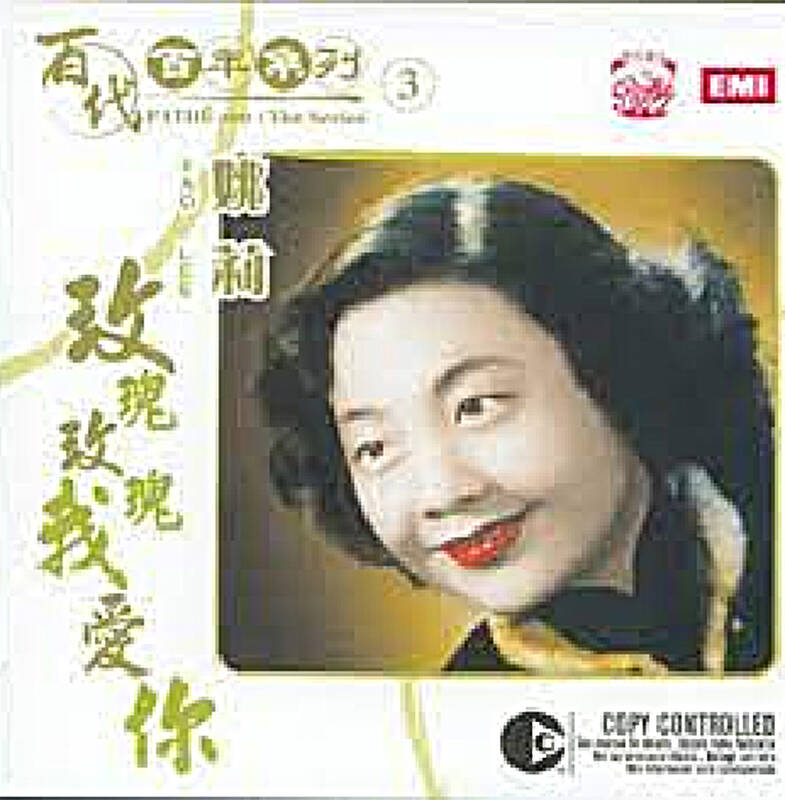

It can be surprising how many of the songs we use to form our identities were originally borrowed from other cultural traditions. My Way might be the ultimate emblem of bootstrapping American individualism, but the tune, popularized by Frank Sinatra in 1969, was actually borrowed from a French ballad from two years earlier, Comme d’habitude, a song by Jacques Revaux about falling out of love. And closer to Taiwan, Teresa Teng’s Tian Mi Mi (甜蜜蜜) may have been elevated by Teng’s angelic voice to the firmament of iconic Mandarin love songs, but the melody actually came from a traditional Indonesian folk song.

These and other songs that cross borders will be the subject of a talk by local music historian Eric Scheihagen on April 14 at the Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation in Taipei: “Rose, Rose, I Love You & Others—on Transnational Asian Popular Songs.” Attendance is free with advance registration, and unusually for Schiehagen, the talk will be in English –– more often than not, his lectures are in Mandarin under his Chinese name Xu Rui-kai (徐睿楷).

OBSESSIVE MUSIC COLLECTOR

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

Scheihagen, a legal translator who has the slightly unkempt appearance of one who keeps to the back of the office, is an obsessive music collector who is slowly becoming recognized as one of Taiwan’s leading music historians. Since the early 2000s, the 53-year-old has co-hosted Chinese-language shows on three Taiwanese radio stations, along the way receiving two Golden Bell nominations. He has also written liner notes for local record companies Wind Music, Big Trees Music and Taiwan Colors Music, curated and contributed to exhibitions on Taiwan music history, and frequently guest lectures at universities around the island.

“He’s a living encyclopedia of music,” says Trees Music founder and academic Chung Shefong (鍾適芳). “Eric’s contribution as a researcher and collector of Taiwanese popular music could well merit its own chapter in this history.”

“I’ve never regarded Eric as a foreigner,” she adds, saying that when hearing him talk about Taiwanese music history, “it’s very difficult to feel that he is discussing a ‘foreign’ culture, as he’s more thoroughly immersed in it than any of ‘us.’”

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

When I ask the size of his collection, he just gives me an exasperated look.

“It’s really hard to estimate,” he shrugs.

In Scheihagen’s too-small apartment in New Taipei City’s Tamsui District (淡水), cabinets and shelves are overstuffed, table tops are piled high and if he invites you to sit on his sofa, he will probably have to move a stack of records or books to make space for you to sit down.

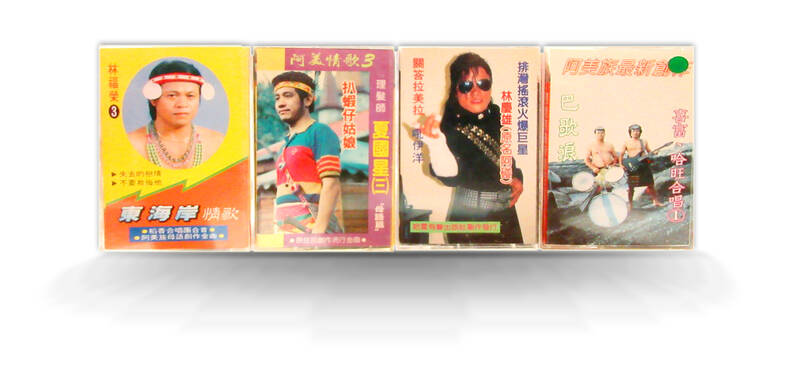

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

“For vinyl, I have at least a thousand records, but how many over a thousand I really don’t know. For CDs, probably at least three or four thousand, and then there are the cassettes and eight tracks, which are….?” he says.

So far, he has digitized at least 5,000 albums, but doesn’t know what percentage of his collection that accounts for, he says.

The most unique areas of Scheihagen’s collection reflect his personal obsessions and idiosyncrasies: the emergence of rock ‘n’ roll in Taiwan, banned songs of the Martial Law era and an unparalleled collection of early Aboriginal pop music from the indigenous communities of southeastern Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

INDIGENOUS MUSIC

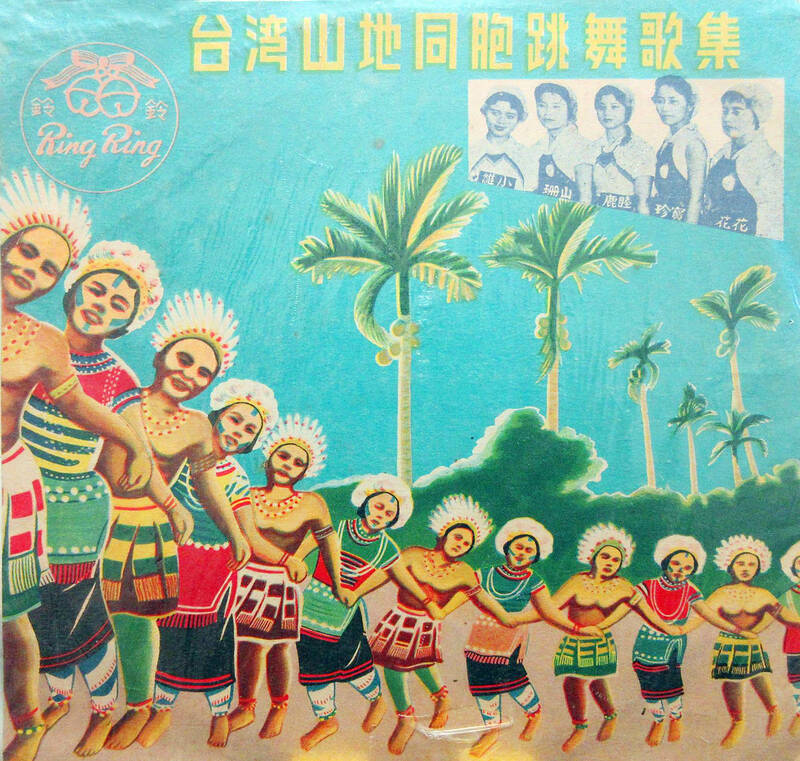

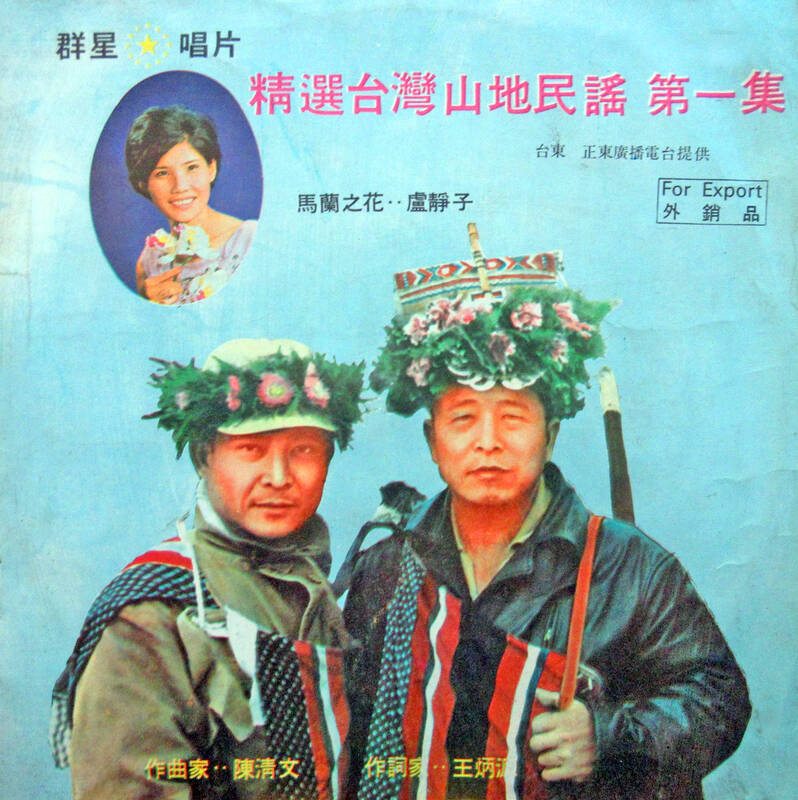

Though largely forgotten, a niche recording industry for the music of indigenous communities date back to the 1960s, which began with ethnographic or world music LPs, but by the 1980s, developed a new strain of “abo pop,” bawdy and comic songs sung in a mix of Mandarin and Austronesian languages. They were sold on cassette tapes almost exclusively within Taiwan’s indigenous-heavy regions of Pingtung, Taitung and Hualien counties, says Scheihagen.

He discovered this music around 1999 when he chanced into a small, specialty record shop in Taitung, Shan Wang Music (杉旺音樂城), which turned out be a treasure trove of the genre.

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

“The walls were lined with hundreds and hundreds of these cassette tapes, all Aboriginal music. Even then, a lot of it was actually from the early 1980s. I had never even heard of any of this stuff before,” he says.

Virtually all of the Abo-pop cassettes from the 1980s came from two record companies, Hsin Hsin Records and Tapes (欣欣唱片) in Tainan and Jen Sheng (振聲視聽) in Chaojhou Township (潮州), Pingtung County. Both were owned by Han Chinese and released other genres besides Abo pop.

The first record company with an indigenous founder to enter into this picture, Harlay Records (哈雷唱片), also based in Chaojhou, appeared in the early 1990s and “pretty much only released aboriginal music,” Scheihagen says.

Photo courtesy of Eric Scheihagen

As Scheihagen immersed himself in this music, he found “there was absolutely no information on this,” he says. So he personally tracked down labels and pestered record shops to photocopy their catalogs. But even to this date, the trend is little known and receives almost no academic attention.

His research eventually uncovered a few of Abo-pop’s breakout hits, like the song Poor, Poor Man (可憐落魄人). Originally recorded in Taitung by Puyuma singer Tseng Hsiao-yu (鄭曉玉), a 1981 version released in Taipei by another Puyuma singer Chen Ming-jen (陳明仁) went on to sell half a million copies.

“And this was at a time when Teresa Teng was only selling 100,000 to 200,000 with each album,” he said.

Originally from Texas, Scheihagen came to Taiwan just out of college in 1992 to get a taste of Asia and teach English.

“In those days you heard current Mandarin pop songs everywhere. They were playing them in shops, night markets, all over the place,” he said.

He was already music obsessed, but a taste previously trained on American classic rock — “Beatles, Queen, Led Zeppelin, Genesis and bands like that” — retargeted itself towards Taiwanese pop. To process all this new music, he started making his own mix tapes, choosing personal favorites and popular songs, while his Taiwanese girlfriend (who later became his wife) introduced him to “the singer-songwriter type ballads that I wouldn’t necessarily get into on my own.”

SCARCE RESOURCES

Those were his first steps down the rabbit hole. But in trying to understand the history, he quickly ran into a wall.

“What I discovered is there was no comprehensive encyclopedia showing all the historical details. Nothing like Allmusic.com or one of those sites,” where he could find release dates or artist and label bios.

The only resource then available was The Best 100 Albums in Taiwanese Popular Music (台灣流行音樂100最佳專輯), a book first published in 1993 and later updated to The Best 200 Albums in 2008. Thousands of recordings however remained almost completely undocumented. Even now in the age of Wikipedia, info on many pre-1980 recordings is a complete black hole.

“For certain records I was curious about, the only way to find out for sure, was to actually find the original recordings or maybe look for references in newspapers,” says Scheihagen. “Most records didn’t even have liner notes, and of the records that did, sometimes they weren’t reliable.”

By the late 1990s, Scheihagen was on his way to becoming a serious collector. At that time, compact discs had all but rendered vinyl obsolete and radio DJs were liquidating their personal collections, which ended up in Taipei’s used record stores.

“It was a lot of stuff that you could never find today, or if you could, definitely not at that price. The records were all flat priced at NT$100 or NT$200,” he says.

Now, with the resurgence of vinyl, “there are a lot more collectors, and the prices are getting really ridiculous.”

Some records that Scheihagen once bought for peanuts, like 1980s releases by Hong Kong rock band Beyond or Taiwanese pioneer Lo Ta-yu (羅大佑) now routinely sell online for around NT$30,000 or more.

LECTURE

Over time, Scheihagen’s collection and DIY research became known among Taiwan’s music heritage crowd, and these friends introduced him to the Lung Yingtai Cultural Foundation, resulting in the upcoming talk.

As to the topic of transnational songs, he says, “I wanted to focus on songs that didn’t just cross boundaries –– for example, a lot of Japanese songs were rewritten with Mandarin lyrics in Taiwan in the 1960s, but they didn’t necessarily go anywhere else –– but songs that went in multiple direction with many versions in different countries and languages.”

These will include stories like that of the 1940 Shanghai-produced Mandarin hit Rose, Rose I Love You, which broke out from the Chinese world when it first aired on the BBC in 1951. Among British listeners, it became an instant hit and was re-recorded in multiple English versions, one of which rose to the third spot on America’s Billboard pop chart later the same year.

Other songs to be discussed originated from Okinawa, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.

How long will the talk last?

“I have this problem,” says Eric. “Even with this current talk, at the start they said 45 minutes. I’m like 45 minutes! Even two hours is too short.”

He will do his best to squeeze it into 60 minutes, with a 15-minute Q&A.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,