IN 2002 Thomas Hertog received an e-mail summoning him to the office of his mentor Stephen Hawking. The young researcher rushed to Hawking’s room at Cambridge. “His eyes were radiant with excitement,” Hertog recalls.

Typing on the computer-controlled voice system that allowed the cosmologist to communicate, Hawking announced: “I have changed my mind. My book, A Brief History of Time, is written from the wrong perspective.”

Thus one of the biggest-selling scientific books in publishing history, with worldwide sales credited at more than 10 million, was consigned to the waste bin by its own author. Hawking and Hertog then began working on a new way to encapsulate their latest thinking about the universe.

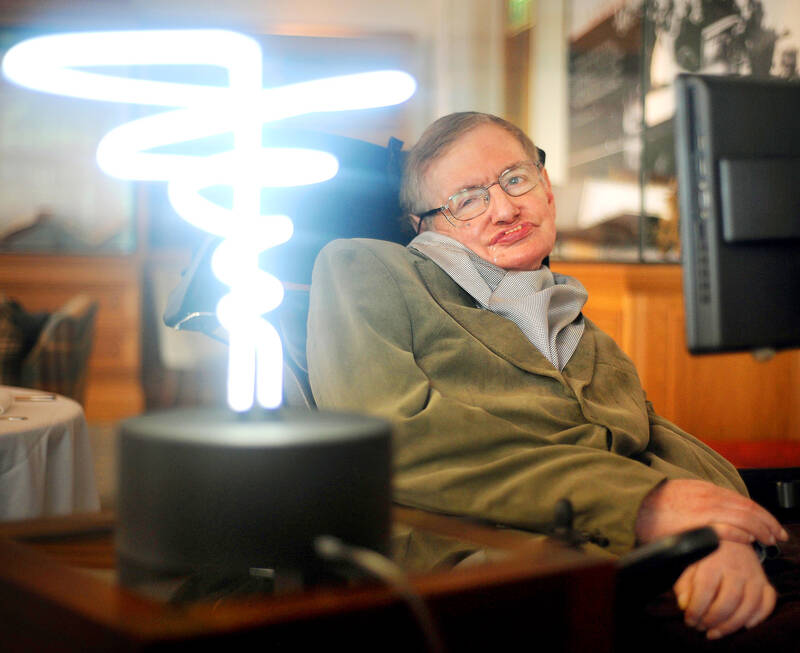

Photo: AP

Next month, five years after Hawking’s death, that book — On the Origin of Time: Stephen Hawking’s final theory — will be published in the UK. Hertog will outline its origins and themes at a Cambridge festival lecture on March 31.

“The problem for Hawking was his struggle to understand how the universe could have created conditions so perfectly hospitable to life,” says Hertog, a cosmologist currently based at KU Leuven University in Belgium.

Examples of these life-supporting conditions include the delicate balance that exists between particle forces that allow chemistry and complex molecules to exist. In addition, the fact there are only three dimensions of space permits stable solar systems to evolve and provide homes for living creatures. Without these properties, the universe would probably not have produced life as we know it, it is argued by some cosmologists.

Photo: EPA-EFE

Hertog and Hawking were set on hammering out explanations for this state of stellar uncertainty after the latter had decided his previous attempts were inadequate.

“Stephen told me he now thought he had been wrong and so he and I worked, shoulder to shoulder, for the next 20 years to develop a new theory of the cosmos, one that could better account for the emergence of life,” Hertog said.

It was a remarkable collaboration but not an easy one. When he was 21, Hawking had been diagnosed with an early onset slow-progressing form of motor neurone disease that gradually paralyzed him.

By the time he began working with Hertog, he had been appointed Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge University, one of the world’s most prestigious academic posts (Isaac Newton was a previous holder), and had produced a series of remarkable theories about general relativity, black holes and the origin of the universe as well as his bestseller A Brief History of Time. However, his condition had deteriorated. He was in a wheelchair and could only communicate using a small computer from which he selected words delivered by a speech synthesizer.

“Halfway through our collaboration, he lost the remaining strength in his hand to press the clicker which he used to converse,” says Hertog. So Hawking switched to a sensor mounted on his glasses that could be activated by twitching a cheek muscle, but eventually even that become too difficult.

He slowed from a few words per minute to several minutes per word, Hertog said. In the end, communication stopped.

“I used to position myself in front of him and fire questions and would look into his eyes to see if he was agreeing or disagreeing. By the end, I could detect several levels of no and several levels of yes with a few in between.”

It was out of these “conversations” that Hawking’s final theory was born and, in conjunction with Hertog’s own analysis, they form the basis of On the Origin of Time, a book that takes its title from Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

“In the end, we both came to think of physics in a way much more like how we think of biology. We have put physics and biology on the same footing.”

According to Hertog, On the Origin of Time deals with questions about our place in the universe and what makes our universe fit for life. These questions were always in the background in their scientific publications.

“What I have done for this book is to make these questions central and tell our story from that perspective. Stephen and I discovered how physics itself can disappear back into the big bang. Not the laws as such but their capacity to change has the final word in our theory. This sheds a new light on what cosmology is ultimately about.”

According to Hertog, the new perspective that he has achieved with Hawking reverses the hierarchy between laws and reality in physics and is “profoundly Darwinian” in spirit.

“It leads to a new philosophy of physics that rejects the idea that the universe is a machine governed by unconditional laws with a prior existence, and replaces it with a view of the universe as a kind of self-organizing entity in which all sorts of emergent patterns appear, the most general of which we call the laws of physics.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she