March 6 to March 12

A large, grisly painting of emaciated passengers suffering on the Thanh Phong vessel hung for years in the exhibition hall of the Vietnamese refugee camp in Penghu. One of the figures appears to be hacking away at the head of a dead body.

All visitors to this camp, many of them soldiers and students, were brought to this display to learn about the evils of communism and how the Vietnamese suffered greatly after the fall of Saigon in 1975.

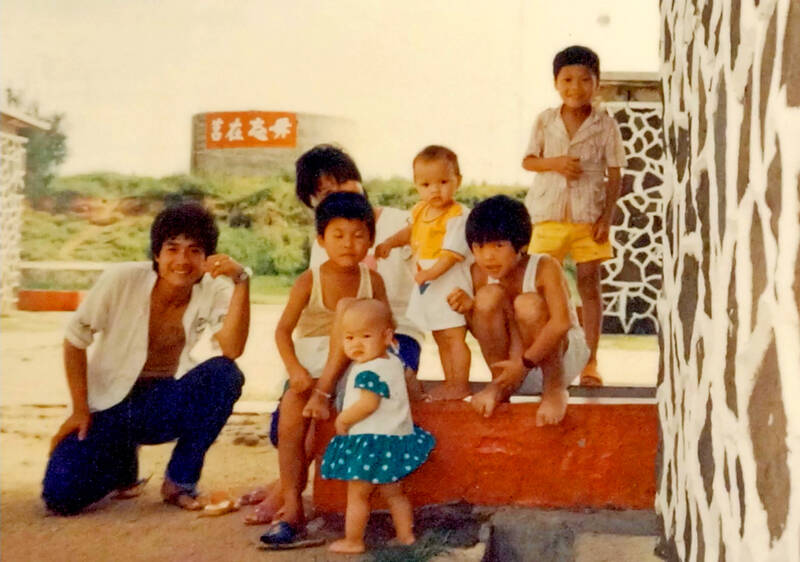

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

“We want our readers to fully realize that if they don’t fight for their freedom, they’ll end up drifting at sea like the Vietnamese refugees,” states the introduction of the 1980 book, True Record of the Penghu Vietnamese Refugee Camp (澎湖越南難民營實錄). “These people would rather risk perishing in the ocean than become sacrificial animals to the communists!”

More than 2,100 refugees passed through Penghu between 1977 and 1988, but it was the tragic events of the Thanh Phong — where only 34 of 146 passengers survived 66 brutal days at sea in 1978 — that captured national attention and became widely used to fuel anti-communist sentiment.

The harrowing ordeal was embellished into a television series and a movie, but it’s only a small part of the Public Television Service (公視) documentary, A Camp Unknown (彼岸他方), which aired last Thursday. The film, which covers the entire history of post-World War II Vietnamese migration to Taiwan, can be watched on the station’s Web site, but doesn’t have English subtitles.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

Executive producer Liu Chi-hsiung (劉吉雄) began researching and documenting the larger camp in Baisha Township (白沙) on the eve of its dismantling in 2003. Today, no trace of it is left, and many Penghu locals don’t even know that it existed. People stayed until they were resettled in the US, Canada or Europe, some waiting for years.

DESTINATION NOT TAIWAN

“Every country is known for exporting certain raw materials or products. But for communist countries, their top export is refugees,” states True Record of the Penghu Vietnamese Refugee Camp.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

That might be sensationalist writing, but millions of residents fled Vietnam before and after 1975, with countless dying at sea from piracy, storms and accidents. Shortly before the fall of Saigon, Taiwan had already accepted about 4,000 ethnic Chinese refugees, who were temporarily settled in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan was no longer part of the UN and was not a prime destination for ethnic Vietnamese refugees, who headed for other Asian countries as far as Japan. For example, compared to the 2,100 who arrived in Penghu, more than 200,000 reached the shores of Malaysia and Hong Kong. The Thanh Phong was trying to reach Malaysia, but later changed course to the Philippines after the tides changed.

According to the documentary, the effort in Taiwan was started by the Catholic Caritas Internationalis and carried out by the semi-official Free China Relief Association (中國大陸災胞救濟總會).

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

“We told the government that it was a good chance for the Republic of China (ROC) to prove through humanitarian assistance that it’s not a cold hearted country,” Lee Ling-ling (李玲玲) from Caritas says in the film.

The government later directed Taiwanese ships to rescue any refugees they found drifting in the ocean.

REDISCOVERY

The first refugees to Penghu arrived in June 1977 and were housed in a military facility in Siyu Island (西嶼). The Baisha camp was completed in December 1978.

The Baisha camp provided occupational training and employment opportunities along with basic food and shelter, and interviewees in the film say that they were treated quite well in comparison to the refugees they met who arrived on the shores of other Asian countries.

One man said that on the plane to the US, he was embarrassed that he was wearing a suit while his compatriots who stayed in camps in the Philippines were wearing ragged clothing.

Liu writes in a Router: A Journal of Cultural Studies (文化研究) article that he first heard of the existence of the camps while working at a military publication in Penghu as part of his mandatory military service. He asked a few locals, but soon forgot about it after not being able to find much information. The next time it came up was in 2003, when he was told that the Baisha camp was to be demolished within three months .

He rushed to the site, and the only remaining evidence was a plastic plaque with the date of the camp’s establishment and a message reminding people to learn from Vietnam’s fate. This began his two-decade long foray to uncover the remaining details.

RETURNING TO PENGHU

A total of 106 babies were born in both camps, and the documentary features a few who returned recently to find their roots.

Ms. Le was one of the youngest survivors from the Thanh Phong, and the face of a cover story in a military report about the incident. She generally had fond memories of the camp, noting that she no longer had to worry about survival and was treated well by the staff, who allowed her to roam free in the area. But it also reminded her of the tragic fate of her mother, sister and two brothers, who were among the 30 people who died on the rescue boat to Taiwan.

According to accounts in the 1980 book, the boat had gone through its food supplies after being stranded on a coral reef, and had also exhausted the shellfish they could find in the area. People started collapsing, and eventually the dying told the living to consume their corpses.

They refused at first, but as the situation worsened, they reluctantly did so after obtaining approval from the relatives of the deceased. They could barely walk or eat by the time they arrived in Penghu.

According to the documentary, what wasn’t mentioned in official accounts was that the captain of the rescue boat drove slowly on purpose and extorted money and valuables from the refugees in exchange for food and supplies. The captain was reportedly arrested and punished, but there seems to be no record of it.

Ms. Le spent three years in the camp before being resettled along with her brother in Belgium.

By the time of the camp’s closure in 1988, most of the 192 people remaining were North Vietnamese refugees who weren’t considered political cases and had trouble getting accepted to the US. So the Taiwanese government allowed them to stay.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she