Feb 27 to Mar 5

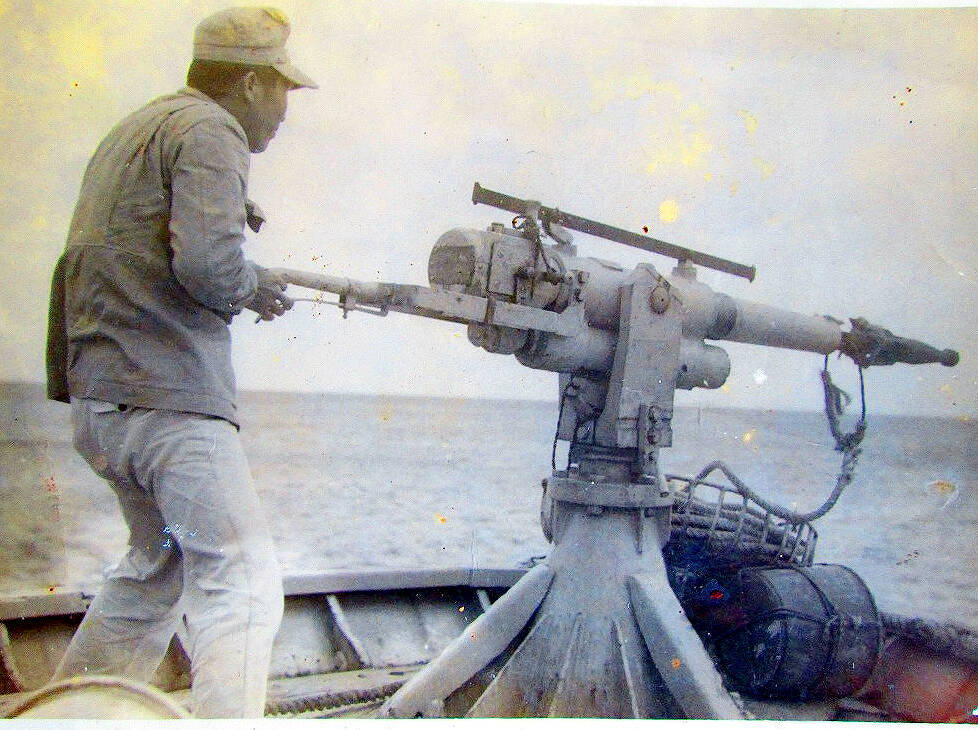

Tsai Wen-chin (蔡文進) waited and waited for the right moment to fire the harpoon cannon. He tells Yang Chen-yuan (楊政源) in the 2013 book, Sea Blue Blood (海藍色的血液) that the distance between the ship and the whale was twice as far as what he had practiced.

With the Japanese chief harpoonist urging him on and the entire crew getting restless, Tsai fired his first shot. It was a success. On that trip in the mid-1950s, Tsai hit the marks on both shots he fired, while the chief harpoonist got eight out of 10.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

“That’s 80 percent vs 100 percent,” he said proudly nearly 60 years later, after whaling had long been banned.

In July 1981, Tsai’s 25-year career came to an end when, facing international pressure, the government outlawed the practice and revoked all whaling licenses. Launched by the Japanese in 1913 and restarted in 1955, it was a lucrative industry in the Hengchun Peninsula (恆春) — the torii gate in front of the Eluanbi Shinto Shrine was even made of whale ribs.

For the past 15 years, local researchers led by Nien Chi-cheng (念吉成) have been interviewing the aging whalers and collecting historic material to piece together this often-forgotten past. On Monday, the Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) reported that Nien will soon be holding an exhibition with never-seen material in Hengchun.

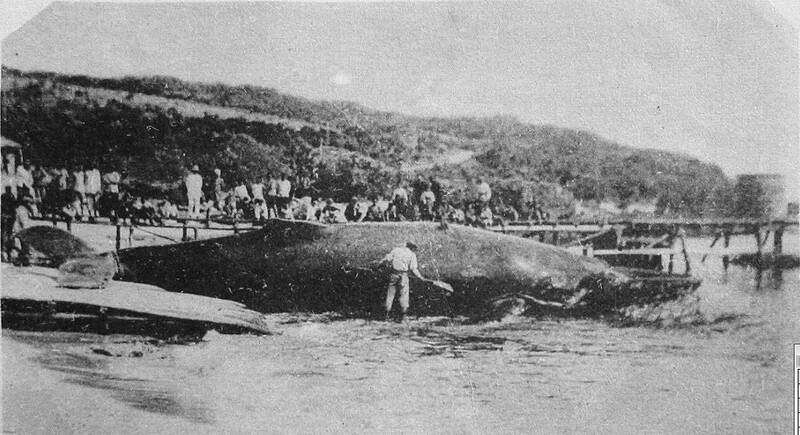

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repositories

“The Hengchun peninsula was once a thriving habitat for whales, but today there are only occasional surprise sightings,” Nien says. “This exhibition is also to reflect on human greed, and to preserve this past of Hengchun.”

A NEW INDUSTRY

Qing-era documents regarding whales in Taiwan indicate that residents would use their meat and blubber whenever they washed ashore, whether dead or alive. Commercial whale hunting did not begin until 1913, when a Japanese company set up operations in today’s Nanwan (南灣) in Kenting National Park.

Photo: Tsai Tsung-hsien, Taipei Times

Using smaller boats and lacking processing equipment, and this venture fizzled out after two years. According to a 1994 Fisheries Extension article by Hu Hsing-hua (胡興華), in 1920 the governor-general’s office commisioned a Japanese whaling company to restart operations in Nanwan.

They managed to kill 34 whales that year, proving that the industry was feasible, and the government then imported two whaling ships fitted with harpoon cannons from Norway and hired Norwegian experts to operate them. The processed meat and oil were sent back to Japan. They were rarely consumed by locals.

To prevent overhunting, the government only allowed two ships to operate at a time between December and March on the waters between Hengchun and Taitung. The three main species hunted were humpback whales, sperm whales and fin whales. The most bountiful year was 1929, with 62 animals hauled ashore.

Operations were suspended in 1943 due to World War II. In 1953, Hsiang Teh Fishery Company (祥德漁業) began discussions with a Japanese counterpart to revive Taiwan’s whaling industry, and after four years of discussion, they began operations in Banana Bay (香蕉灣) further to the southeast. The Japanese provided the ships and personnel, while the Taiwanese built the processing facilities and port. They split the profits 60-40.

The first voyage lasted over a month, returning home with four humpback whales. Tsai was one of the company’s first Taiwanese crewmembers, joining as a harpooning assistant. As before, almost all of the bounty was exported overseas.

“The meat is not suitable for Taiwanese tastes,” Tsai replies when Yang asks if Hengchun residents consumed whale meat. He was given a few cans by the company to try — “It really tastes terrible!”

UNSATISFACTORY YIELDS

Due to unsatisfactory yields, the Japanese company pulled out in 1960. Hsiang Teh then joined forces with the Provincial Fisheries Agency, who retrofitted the patrol boat “Huyu No. 1” (護漁一號) as the first Taiwanese-made whaling vessel.

This partnership ended three years later again due to lack of productivity, and Hsiang Teh then purchased a Japanese ship to do it on their own. They soon gave up.

Huang attributes the failure to lack of technical experts as well as unstable supply. Under the agreement, five Taiwanese staff were allowed on the ship, but they were only able to provide three due to a shortage of trained whalers. And unlike Japan, where its whaling ships could move around the country according to migration patterns, Taiwan’s ships and processing facilities often sat idle for much of the year.

The allure remained, however, and in 1976, Ming Tai Aquatic Products (銘泰水產) obtained the 600-ton Sea Bird (海雁號) and set out in April with a crew of 26. During eight journeys in two years, it caught about 290 whales, and their success spurred other companies to vie for a piece of the pie.

While Taiwan was not part of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), the government still limited the licenses it issued and drafted laws to regulate the industry according to international standards. Only three more licenses were handed out by 1979.

END OF THE LINE

In 1978, the IWC began tightening restrictions on whaling, and also applied pressure on Taiwan. William A. Brown, director of the newly established American Institute in Taiwan’s Taipei office, wrote to the government a year later, noting that the US was concerned about Taiwan’s expansion of its whaling industry at a time when others were contracting theirs. He sternly warned that noncompliance could lead to the US boycotting Taiwanese aquatic products.

The government responded that they would not encourage further development, but maintained that their limited activity would not affect the whale population much. The Americans continued to pressure Taiwan over the year, accusing them of “smuggling” whale meat into Japan as products of South Korea and even trying to block the nation’s exports to Japan through the IWC.

What’s ironic is that due to Taiwan’s international status, it could not join the IWC, and was not allowed to attend the organization’s 1980 conference in London, even as an observer. But later that year, the government released a detailed report of its whaling activity and decided to completely ban the industry.

In 1990, the Earth Trust organization recorded a video of a bloody dolphin hunting drive in Penghu and screened it in the US, leading to massive international outcry. Taiwan had just enacted its Wildlife Conservation Act (野生動物保育法) a year earlier, and this event led to all whales and dolphins being placed on the protected list.

With whaling banned, Hu suggested the rise of a new industry — whale watching.

In July 1997, the Haijing (海鯨號) vessel embarked on the nation’s first whale tourism voyage from Hualien. The ship survived a fire last year and is still in operation.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of