It’s not everyday that neurologists and neurosurgeons are invited to provide input on how to shoot people in the head.

Just a week earlier, on Dec. 15, 1990, Taiwan’s first death row inmate to voluntarily donate his organs to medicine was executed. But due to difficulty controlling blood loss, the heart and liver were rendered unusable. Before this, prisoners were shot through the heart.

National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH) chief surgeon Lee Chih-hsueh (李治學), who had been trying to get people to donate organs to no avail, devised the inmate program and wanted expert advice on how to fire the bullet to minimize organ damage.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lee had made history in 1968 as a member of the team to perform Asia’s first successful kidney transplant. But due to the public’s reluctance to become donors stemming from the traditional belief in keeping one’s body whole after death, fewer than 1,000 transplants were completed by 1990.

“This reluctance is gravely affecting the advancement of medicine,” Lee told the United Daily News (聯合報) in 1983.

Despite protests from international human rights groups and Western diplomats, using death row inmate organs became a standard practice until it ceased under public pressure in 2011. The use of organs from executed prisoners was banned in 2015.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Medical Alliance for Labor Justice

Frustrated by the lack of change in public’s willingness to donate organs, Lee continued to seek other ways to procure organs, including transplanting animal parts into humans. He unexpectedly died from aortic dissection on Feb. 13, 1995, and his obituary remembers him as the “Swift Blade of NTU” (台大快刀手).

TRANSPLANT PIONEERS

Lee Chih-hsueh first came to prominence in 1968 at the age of 31, when he was named one of the 19 physicians who would be attempting Asia’s first live kidney transplant under attending surgeon Lee Chun-jen (李俊仁).

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Lee Chun-jen had been preparing for the moment for three years, first heading to the US to study at an organ transplant research center, and then experimenting on hundreds of dogs with his team. They kept a 24-hour watch over the animals, checking their heartbeats, blood pressure, white blood cell count and administering anti-rejection drugs. The entire effort cost about NT$140,000 (nearly NT$1 million today).

The recipient was Wu Chen-hsiang (吳振祥), who suffered from uremia, and the donor was his father. After the surgery, they closely monitored Wu until they deemed the procedure a success.

“Nobody supported NTUH’s endeavor a few years ago, and now that they succeeded, everyone is rushing to congratulate them,” a United Daily News article states. The hospital called for more donors, as they couldn’t take kidneys from live people each time, and also announced their plans to attempt a heart transplant next.

There had only been about 20 heart transplant attempts in the world up to that point, with a low survival rate, but the NTUH team still wanted to proceed. It took until 1987 for them to succeed.

PUSHING THE ISSUE

Fast forward to 1993. Taiwan remained at the region’s forefront of the field, with Chen Chao-lung (陳肇隆) completing Asia’s first kidney transplant in 1984. The government also passed the Human Organ Transplant Act in 1987 to legally allow the use of organs from brain-dead patients. But Lee Chun-jen lamented in an organ procurement journal that despite their early success, the number of subsequent cases had been extremely low due to a lack of donors.

“Between 3,500 and 4,000 people die from car accidents each year, which should amount to ample organ sources, but it’s really hard to promote the concept to the public,” he said.

In May 1983, the Minsheng Daily (民生報) reported that an old man named Wu Kuo-chao (吳國超) decided to donate his body to NTUH in honor of Lee Chih-hsueh, who performed gall bladder stone surgery on him four years earlier.

“Wu hoped that his decision would inspire others and overturn societal superstitions. He also urged the 1,500 residents at his senior home to do the same,” the report stated. Lee publicly thanked Wu for the support.

The effort received a boost in late 1990, according to a 1991 Taiwan Panorama (台灣光華) article, when the family of a brain dead police officer who was shot by a criminal agreed to donate all his organs. Three more death row prisoners volunteered their organs in January 1991, benefitting more than 40 patients.

Lee Chih-hsueh told Taiwan Panorama that obtaining kidneys should be the least problematic since humans only need one to live. But the nation only saw about 80 transplants in 1990, with more than 600 patients on the waiting list each year. He later took his expertise overseas, performing Vietnam’s first kidney transplant in 1992 and completing eight more that year.

DEBATE OVER EXECUTIONS

Despite international pressure, Lee insisted that there was nothing unethical with taking the organs of someone who was condemned anyway.

Leaving the ethical issue of the death penalty aside, concerns included the possibility of judges colluding with doctors to harvest organs, and problems with determining one’s death. Legally, doctors can only declare a person brain dead after six hours of observation. Executed prisoners, however, are transported to the hospital for organ removal 20 minutes after being shot. There were also concerns that recipients might find out that the transplanted organs came from serious criminals.

In April 15, 1991, an executed prisoner who was declared brain dead was transported to the hospital for organ removal, but he was later found to still have a heartbeat. However, the practice and debate both continued. A 2001 Taipei Times article shows that five out of 12 liver transplants performed in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (長庚醫院) the previous year used organs from executed prisoners.

Despite the nation having ceased the practice in 2011, it technically remained legal until 2020 with the amending of the Regulations for the Execution of the Death Penalty (執行死刑規則).

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

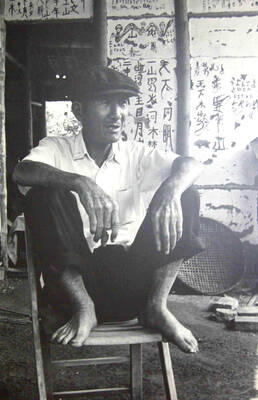

Feb. 20 to Feb. 26 Just a few years removed from the peak of his fame, Hung Tung (洪通) lived alone in a dilapidated house in rural Tainan in the 1980s, working on his art and subsisting mostly on sweet soymilk. His family had moved to Tainan City, but he refused to join them. Neighbors were mostly us

Feb 27 to Mar 5Tsai Wen-chin (蔡文進) waited and waited for the right moment to fire the harpoon cannon. He tells Yang Chen-yuan (楊政源) in the 2013 book, Sea Blue Blood (海藍色的血液) that the distance between the ship and the whale was twice as far as what he had practiced. With the Japanese chief harpoonist

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the