The discovery of dozens of beakers and bowls in a mummification workshop has helped reveal how ancient Egyptians embalmed their dead, with some “surprising” ingredients imported from as far as Southeast Asia, a study said Wednesday.

The exceptional collection of pottery, dating from around 664-525BC, was found at the bottom of a 13-meter well at the Saqqara Necropolis south of Cairo in 2016.

Inside the vessels, researchers detected tree resin from Asia, cedar oil from Lebanon and bitumen from the Dead Sea, showing that global trade helped embalmers source the very best ingredients from across the world.

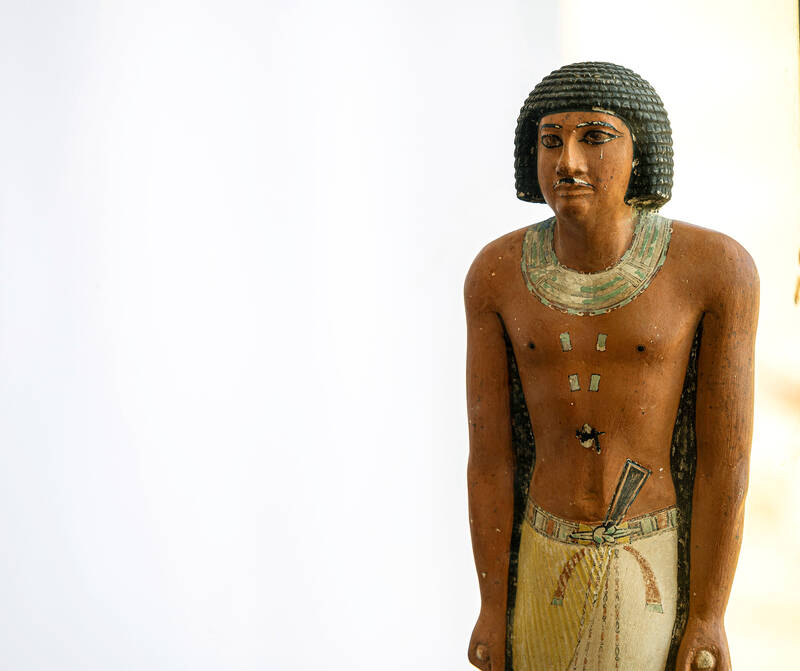

Photo: AFP

Ancient Egyptians developed a remarkably advanced process to embalm corpses, believing that if bodies were kept intact they would reach the afterlife.

The process took up to 70 days. It involved desiccating the body with natron salt, and evisceration — removing the lungs, stomach, intestines and liver. The brain also came out.

Then the embalmers, accompanied by priests, washed the body and used a variety of substances to prevent it from decomposing.

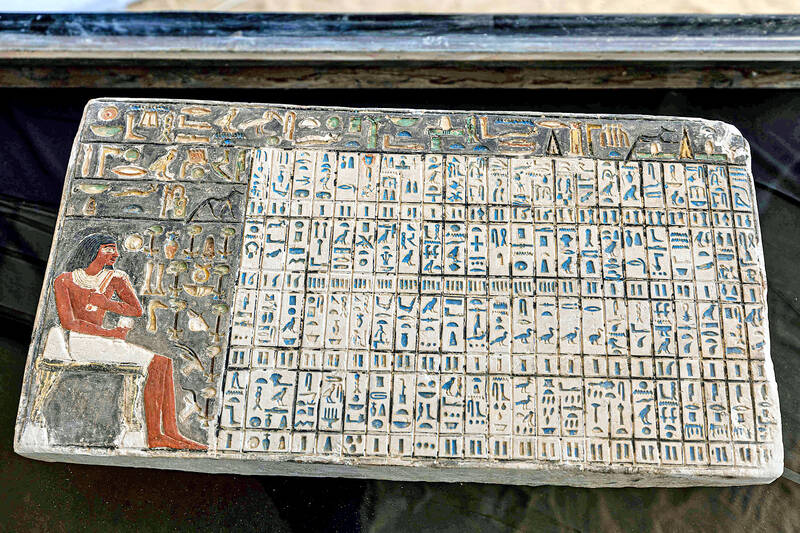

Photo: AFP

But exactly how this was done has largely remained lost to time.

Now a team of researchers from Germany’s Tuebingen and Munich universities in collaboration with the National Research Center in Cairo has found some answers by analyzing the residue in 31 ceramic vessels found at the Saqqara mummification workshop.

By comparing the residue to containers found in adjacent tombs, they were able to identify which chemicals were used.

‘TO MAKE THIS ODOR PLEASANT’

The substances had “antifungal, anti-bacterial properties” which helped “preserve human tissues and reduce unpleasant smells,” the study’s lead author, Maxime Rageot, told a press conference.

Helpfully, the vessels have labels on them. “To wash,” reads the label of one bowl, while another says: “to make his odor pleasant.”

The head received the most care with three different concoctions — one of which was labeled “to put on his head.”

“We have known the names of many of these embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered,” Egyptologist Susanne Beck said in a statement from Tuebingen University.

“But until now, we could only guess at what substances were behind each name.”

The labels also helped Egyptologists clear up some confusion about the names of some of the substances.

The scant details we have about the mummification process mostly comes from ancient papyrus, with Greek authors such as Herodotus often filling in gaps.

By identifying the residue in their new bowls, the researchers found that the word antiu, which has long been translated as myrrh or frankincense, can actually be a mixture of numerous different ingredients. In Saqqara, the bowl labeled antiu was a blend of cedar oil, juniper or cypress oil and animal fats.

EMBALMING DROVE ‘GLOBALIZATION’

The discovery showed the ancient Egyptians had built up “enormous knowledge accumulated through centuries of embalming,” said Philipp Stockhammer of Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology.

For example, they knew that if the body was taken out of the natron salt, then it was in danger of being immediately “colonized by microbes that would eat up the skin,” he said.

Stockhammer said “one of the most surprising findings” was the presence of resins, such as dammar and elemi, which likely came from tropical forests in Southeast Asia, as well as signs of Pistacia, juniper, cypress and olive trees from the Mediterranean.

The diversity of substances “shows us that the industry of embalming” drove momentum for “globalization,” Stockhammer said.

It also shows that “Egyptian embalmers were very interested to experiment and get access to other resins and tars with interesting properties,” he added.

The embalmers are believed to have taken advantage of a trade route that came to Egypt through present-day Indonesia, India, the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea from around 2000 BC.

The Saqqara excavation was led by Ramadan Hussein, a Tuebingen University archaeologist, who died last year before the research was published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the