Jan. 16 to Jan. 22

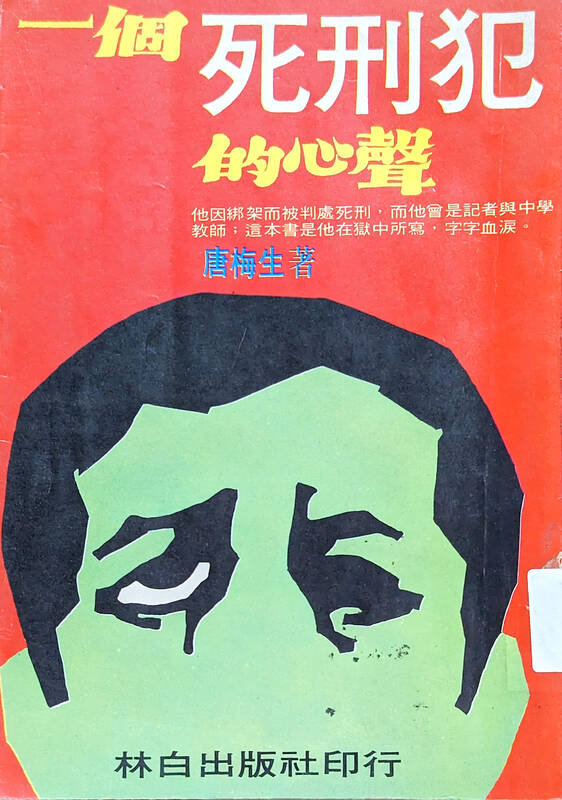

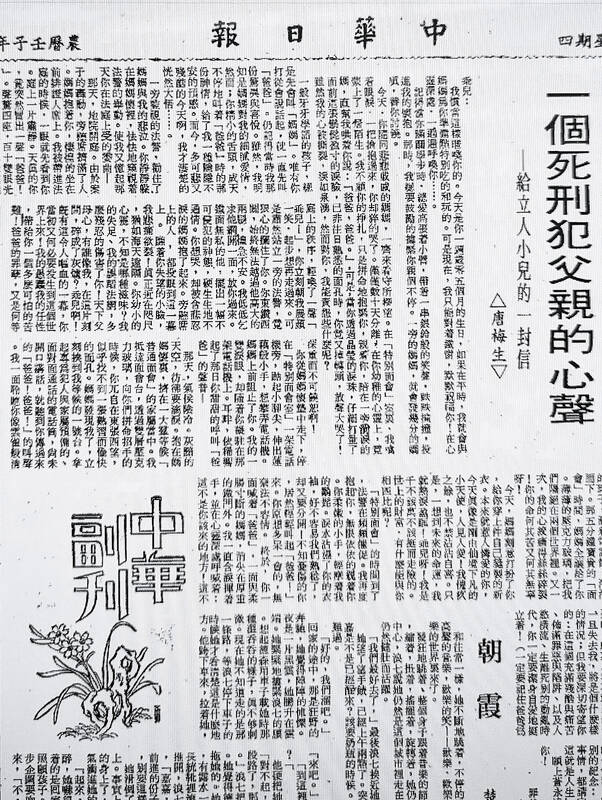

Titled “Confessions of a Father on Death Row,” (一個死刑犯父親的心聲), Tang Chen-huan’s (唐震寰) literary debut was one of sorrow and regret.

It ran in the literary supplement of the China Daily News (中華日報) on Jan. 18, 1972, and marked the beginning of Tang’s literary career, which included several awards and a movie adaptation. He was the nation’s first inmate to pay taxes on book royalties.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The well-liked former junior high school teacher was condemned for kidnapping the children of a businessman who had cheated him out of a large sum of money. Although he returned the kids unharmed, such crimes were punishable by death during the Martial Law era.

“I wrote for nearly 20 hours a day, because I didn’t know if I would be dragged out and executed when the morning came,” he writes in a Xiangguang Magazine (香光莊嚴) article in 1996. “As long as I could still breathe, I wanted to write down all the words I wanted to say … I hoped that those in precarious situations, or those who sought revenge, could see me as an example and refrain from doing something they would regret forever.”

Tang’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1975, and he was transferred to the Taichung Prison. By 1980, he had written 156 essays, short stories and novels, according to a Taiwan Panorama (台灣光華) article.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When the organizers of the 1979 National Army Literature and Arts Award learned that their bronze medal winner was an inmate, they traveled to the prison and held for him a formal ceremony, a move that garnered much public attention. He won the award four more times.

Tang was paroled in May 1985 after serving 12 years and eight months. At the press conference, he again told the public not to do what he did, and performed the hit song Last Night’s Stars (昨夜星辰) before walking out the gates a free man.

WRONG STEP

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Born in Hunan Province, China, Tang joined the Republic of China Air Force at a young age, and was about 17 years old when he arrived in Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1945. He began teaching junior high physics and chemistry in 1956, and ran a lab equipment shop with his wife.

“I was beloved by my students and trusted by my colleagues, and I enjoyed a very happy marriage. I also earned good money,” he writes. “But before I noticed, I had become arrogant. I got carried away, and my self discipline started to wane.”

Tang somehow decided that the kidnapping was the most clever way to handle his predicament, as he did not think direct confrontation or violence would work. He recalls in the 1996 article that if he had actually beaten up the businessman, he would have been charged with assault, which did not carry a death sentence.

“Looking back, It was my destiny for this to happen,” he writes. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be able to share my story with my readers.”

But Tang was furious. He recalls screaming at the judge, “I’m the victim here, you’re putting me on trial while those who swindled me remain at large. Does the law only protect bad people?”

While appealing his death sentence, Tang wanted to do something to calm his mind. The prison wouldn’t allow science experiments, so he picked up a pen and began writing. His first piece described the remorse he felt toward his one-year-old son, and the torment he felt during every visit. He was left in tears when his son called out to him in the courtroom, or innocently played with his handcuffs.

“In this cruel and painful world full of sin and pitfalls, unbridled indulgence and separation between loved ones, you must respect yourself and stand tall. You must remember the lesson of your father being punished for his greed.”

PUBLIC ENCOURAGEMENT

Tang’s moving letter to his son received an outpouring of sympathy from readers, many of whom wondered what landed him in prison. After publishing a letter to his wife, he decided to reveal in the next essay what exactly happened.

Tang didn’t initially know who cheated him, but six months later he found out who was behind the plot. He began scheming ways to exact revenge. On Oct. 26, 1971, he had a female accomplice pretended to be an elementary school teacher, and the ruse enabled them to kidnap the children.

When Tang reached the negotiation spot, he noticed that it was swarming with scary-looking men. Realizing that the thief was probably a gangster, he gave up and released the children. The next day, he was arrested.

While in jail, he picked up a book by then-premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), who wrote: “There are only two people in the world who can enjoy true happiness: those who forever do good and never commit any crimes, and those who have sinned but are able to repent and reform themselves.”

LATER WRITINGS

Tang’s works soon went from autobiographical to creative fiction, most of them containing strong moral messages. His first award-winning story, Bridge (橋), depicted how two rival villages on opposite sides of a river that were able to forgive generations of hatred. His 1985 book, I Kidnapped My Student (我綁架了我的學生), was made into a movie.

There’s not much information about what happened to Tang after his parole. He seemed to have undergone some sort of spiritual awakening in the 1990s, writing a series of self-help books , while avoiding religious scams.

His final book, cataloged by the National Central Library, was published in 1997, by which time he would have been about 70. There’s a section on how to live to 200 years old.

In the introduction, he writes: “If you’re troubled by love, suffering from family conflict, upset due to poor interpersonal relations, desperate due to financial struggles and you’re about to fall apart, before you seek to end your life, call this number. I will turn your life around for free, and open for you a new outlook.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Climate change, political headwinds and diverging market dynamics around the world have pushed coffee prices to fresh records, jacking up the cost of your everyday brew or a barista’s signature macchiato. While the current hot streak may calm down in the coming months, experts and industry insiders expect volatility will remain the watchword, giving little visibility for producers — two-thirds of whom farm parcels of less than one hectare. METEORIC RISE The price of arabica beans listed in New York surged by 90 percent last year, smashing on Dec. 10 a record dating from 1977 — US$3.48 per pound. Robusta prices have

The resignation of Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) co-founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) as party chair on Jan. 1 has led to an interesting battle between two leading party figures, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) and Tsai Pi-ru (蔡壁如). For years the party has been a one-man show, but with Ko being held incommunicado while on trial for corruption, the new chair’s leadership could be make or break for the young party. Not only are the two very different in style, their backgrounds are very different. Tsai is a co-founder of the TPP and has been with Ko from the very beginning. Huang has

A dozen excited 10-year-olds are bouncing in their chairs. The small classroom’s walls are lined with racks of wetsuits and water equipment, and decorated with posters of turtles. But the students’ eyes are trained on their teacher, Tseng Ching-ming, describing the currents and sea conditions at nearby Banana Bay, where they’ll soon be going. “Today you have one mission: to take off your equipment and float in the water,” he says. Some of the kids grin, nervously. They don’t know it, but the students from Kenting-Eluan elementary school on Taiwan’s southernmost point, are rare among their peers and predecessors. Despite most of

A few years ago, getting a visa to visit China was a “ball ache,” says Kate Murray. The Australian was going for a four-day trade show, but the visa required a formal invitation from the organizers and what felt like “a thousand forms.” “They wanted so many details about your life and personal life,” she tells the Guardian. “The paperwork was bonkers.” But were she to go back again now, Murray could just jump on the plane. Australians are among citizens of almost 40 countries for which China now waives visas for business, tourism or family visits for up to four weeks. It’s