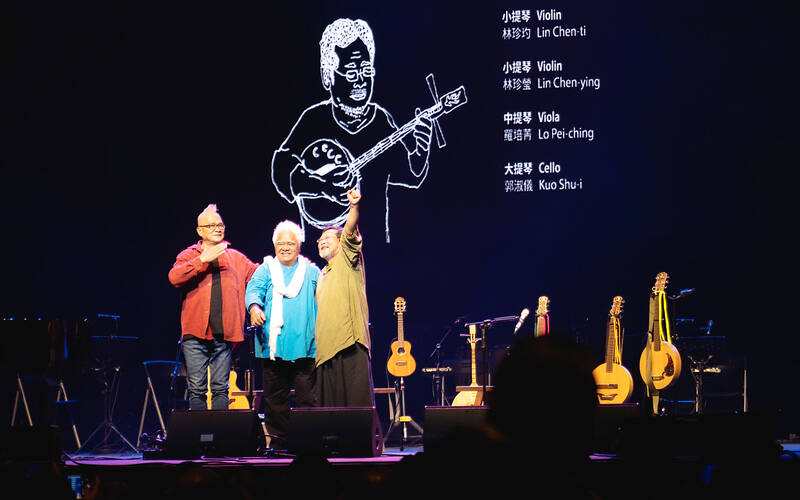

It was a legendary moment for Taiwan’s musical history as Chen Ming-chang (陳明章), Ara Kimbo and Chen Yung-tao (陳永淘) took the stage together, nearly three hours into last Friday’s “Three Greats of Taiwanese Folk Music” concert.

Now in their 60s and 70s, the “wandering bards” (吟遊詩人) not only made their first joint performance, they also co-composed a brand new song for the occasion, sung in their respective mother tongues of Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), Puyuma and Hakka.

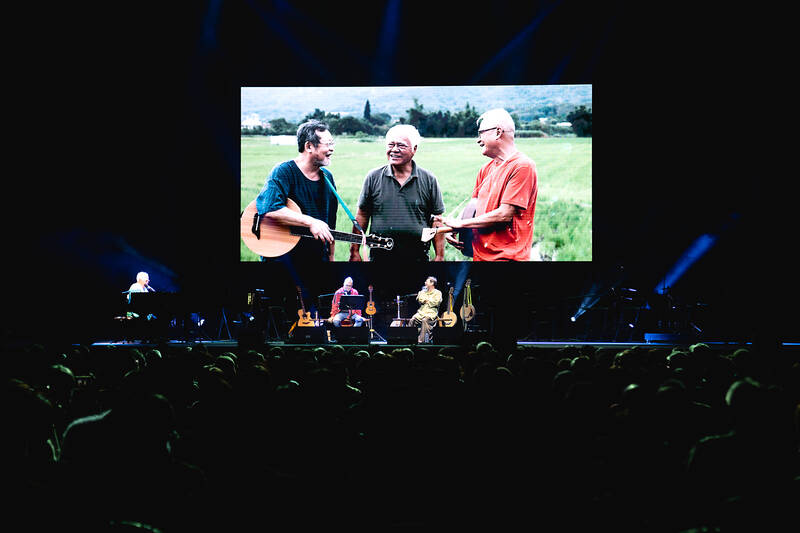

As a music, history and language enthusiast, this show hit all the right notes for me. The seasoned artists had each delivered an entertaining and emotionally powerful set interspersed with intimate footage of them discussing their life and work, but it was still hard to imagine what would come next.

Photo courtesy of Peng Ting-ling

Despite falling under the nativist folk genre and drawing passionately from the land and traditional culture, the three embody quite distinct musical styles and characters, and their banter is heartfelt yet hilarious.

Always smiling and downing kaoliang liquor throughout the show, Chen Ming-chang is free-spirited and unrestrained, singing energetically about drinking, love and the daily lives of ordinary folk. Ara Kimbo’s husky, resonant voice is intense and hits like a brick. It’s controlled yet wild at the same time, often breaking into traditional indigenous melodies. As a long-time activist, many of his songs touch upon the environment and the rights of his people. Sporting a graying mohawk, Chen Yung-tao’s timbre is cleaner but deep and far-reaching. He brings an innocence, playfulness and longing for a simpler past and nature into his songs. He’s also drawn to indigenous culture and plays a mouth harp on some songs.

Their first number was a new rendition of Thinking Back (思想起), a classic Hengchun (恆春) folk tune most famously recorded in the 1970s by Taiwan’s prototypical wandering bard Chen Ta (陳達), who died in 1981.

Photo courtesy of Peng Ting-ling

Chen Ming-chang opens the song strumming on his “ming” lute (明琴), a self-invented three-stringed version of the moon lute, while Ara Kimbo freely harmonizes in his iconic voice, while his fingers dance across the grand piano. Chen Yung-tao joins in later with his acoustic guitar, crooning in Hakka about his childhood in his hometown of Guansi (關西) in Hsinchu County.

“It’s different from what we rehearsed,” one of them quips afterward. “Every time we play it, it’s different,” another laughs. They make similar comments after the next song, Paktow (A Grain of Rice, 一粒米), written last August when the three met up for the first time at Chen Ming-chang’s home in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投).

Ara Kimbo wrote the first part about Chen Ming-chang, commenting on how the mountains in the north resemble the ones in his native Taitung County, and how Chen behaves even more indigenous than he is, especially after he drinks. They each present their impressions of Beitou, and their distinct voices and languages meld together. Not only is the resulting sound moving, I also think of how these languages were once suppressed by the government, and how we have the fortune today to hear them in unison on one of Taiwan’s biggest stages.

Chen Yung-tao’s A Tung’s Song (阿東的歌) follows, with the playful chorus consisting of basic kinship terms in the Paiwan language. He wrote it about a half-Chinese, half-Paiwan friend who only knew two words in the language, and later they studied it together when the Council of Indigenous People released its first teaching material.

The show closes with another Hengchun folk song where they discuss its possible indigenous origins, and Bulai Naniyam Kalalumayan, a Puyuma tune praying for the young men conscripted to fight in the 1958 Second Taiwan Strait Crisis to come home safely. Chen Ming-chang and Chen Yung-tao add in their pleas, as all ethnic groups in Taiwan were affected by this skirmish.

It was already a great show with just their individual performances, but I was really hoping that they would create something new, and not just sing each other’s songs as they were written. And they did not disappoint. Before heading off stage, Chen Yung-tao says, “Let’s do this again next year, shall we?”

I sure hope they do.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on