In June, a video of a teacher cursing in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) began circulating on various social media platforms.

“Don’t be surprised! There’s no hope for Taiwan,” the post accompanying the video reads. “This video shows an online Taiwanese class, and the content is low-class, vulgar and shameless. Only an incompetent government would devise such despicable teaching material.”

Enter the Taiwan Fact Check Center (TFCC, 台灣事實查核中心), which released a detailed report on why the post was inaccurate. First of all, the video was filmed at a university, meaning the government isn’t responsible for its content.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The professor was reading a passage from the short story After Noon (午後), and the emotional, profane monologue came from the kind-hearted protagonist after she decided to stand up against her tormentors. TFCC even spoke to a professor of literature, who said the outburst represented the character’s transformation, and makes sense from a literary standpoint.

However, comments to the fact center’s rebuttal were less than supportive: “The criticisms against the teaching material are true then,” one reads. “I can’t tell if the TFCC actually found out anything!”

Others denounced them for condoning the teaching of vulgar material in class, and some just flat out said that they will never believe anything the center says due to its “affiliations.”

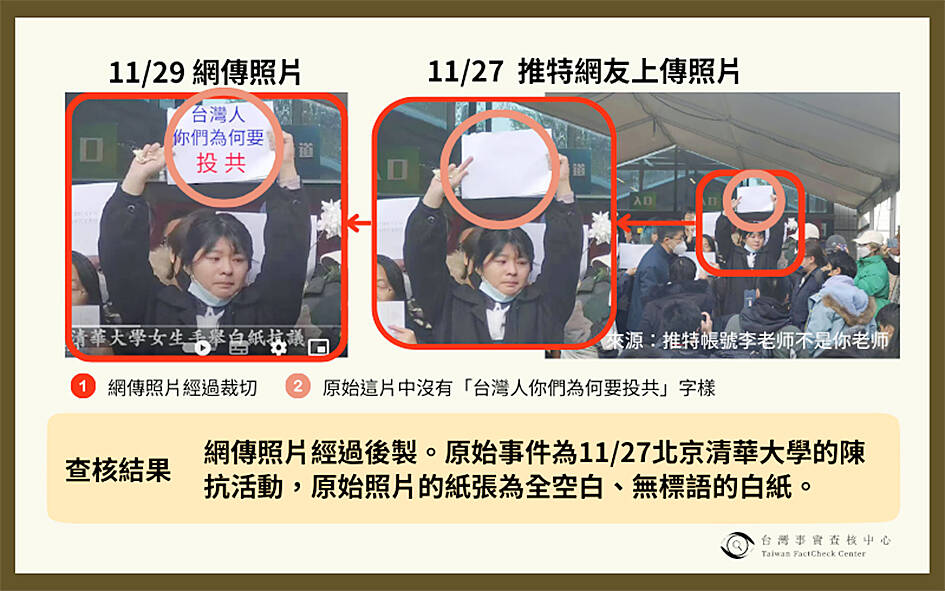

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Fact Check Center

Established in 2018, there’s still a lot of confusion about what they do and who they work for, TFCC deputy editor Claire Chen (陳偉婷) tells the Taipei Times.

“We do not deal with personal criticisms toward politics,” she says. “We can only examine the hard facts in the content. If they want to say that it’s a terrible thing for a professor to curse in class, there’s nothing we can do about that.”

With disinformation and fake news a serious problem worldwide, several fact checking and media literacy advocacy groups have appeared in Taiwan over the past five years. But their reach remains limited and often draws public anger.

Photo courtesy of MyGoPen

MISCONCEPTIONS

According to a TFCC survey conducted early this year, 60.6 percent of respondents express confidence in Taiwan’s fact checking groups, though 57.2 percent have never used one.

Charles Yeh (葉子揚), founder of MyGoPen (麥擱騙), thinks the latter figure should be higher, as many visitors to their booth at last month’s IT Month (資訊月) event had never heard of them or what they do. MyGoPen is one of the earlier fact checkers in Taiwan, launched in 2015 to help Yeh’s mother-in-law, who kept expressing untrue opinions about what food causes cancer and government policies that didn’t exist. She was also susceptible to online scams.

Photo: AP

“At first I just wanted to solve this problem from within my family because it was having a negative impact on our lives,” he says.

Today it’s his full time job. Last month, MyGoPen’s Line chatbot received over 41,000 inquiries, higher than usual due to last month’s nine-in-one elections, but not as much as during the level 3 COVID-19 restrictions last year, Yeh says.

MyGoPen and TFCC are the only two institutions in Taiwan certified by the US-based Poynter Institute’s International Fact Checking Network (IFCN), which requires them to follow strict guidelines such as not accepting government money and not participating in official events.

However, they’ve been attacked by all sides of the political spectrum.

“There’s still a long road to go as far as educating the public about who we are,” Chen says.

The reality is fact checking reports simply are not as appealing to the public as fake news posts. But the groups are trouble-shooting new methods to raise their profile. MyGoPen has just started to make videos in Taiwanese, for example, to target older audiences.

“Our reports are very matter of fact. We don’t write anything sensational, so people are just not as keen to forward them,” MyGoPen project manager Robin Lee (李信誠) says. “A piece of fake news may spread from one to 10 people, while our reports get sent to perhaps just two or three.”

DEBUNKING WORK

Hung Chen-ling (洪貞玲), head of National Taiwan University’s Graduate Institute of Journalism, said in a June TFCC podcast that disinformation no longer primarily targets older folk, but also young people and even social media-savvy children, tailoring the content to each demographic.

Disinformation is often tied to current events or items that affect their daily life, such as food safety and new regulations, Chen says, unless there’s something major going on such as an election or pandemic. Some of the “eating such and such will cause cancer” posts have been circulating around for years, sometimes with just the date changed. But they are still effective.

“[A person’s] point of view is easily affected by [their] political views,” Chen says. “Your preconceptions and ideologies determine whether you believe this information. So we see a lot of old news circulating that we’ve debunked already.”

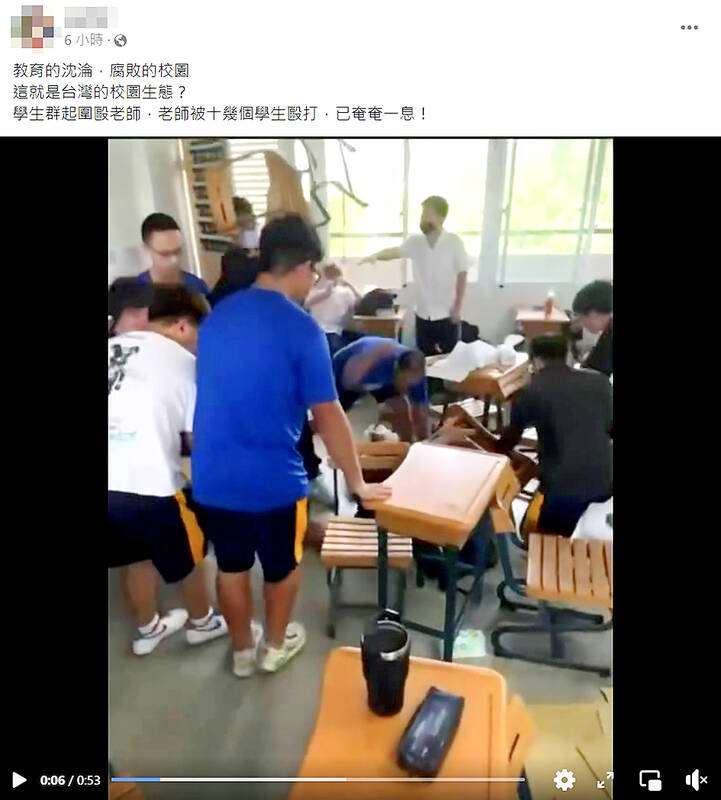

Yeh agrees that most of their queries directly relate to daily life. A lot of the fake information comes from China, where creators may splice together Taiwanese news items, add some riveting commentary and put it on TikTok. Another common query is videos of bullying, torture and other eye-catching behavior that viewers disseminate because they want to track down the culprit.

Interestingly, there are fewer inquiries directly about politics. Yeh says that people generally don’t appreciate it when people in group chats keep posting political content, and also because politics is a sensitive topic, people are reluctant to point out that they’re wrong.

For subjective disinformation posts, both groups have special sections on their Web sites to guide people in how to discern them. For example, TCFF has a section on how to decode political memes, while MyGoPen has a section on how to avoid scams.

COLLABORATION

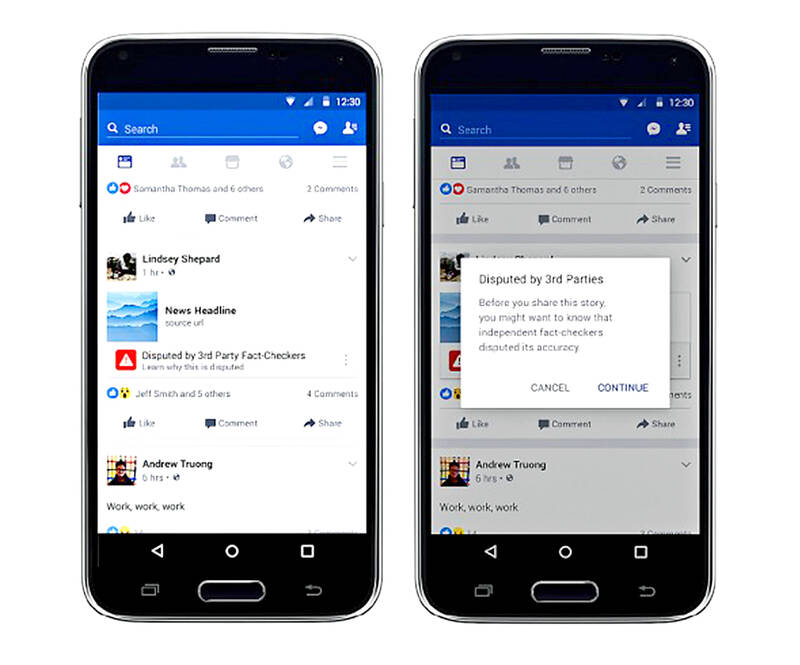

TFCC and MyGoPen assists social media platforms such as Facebook in vetting fake information. If found to be false, it will be marked and its reach will decrease. Whether the account gets banned or the post deleted is not up to them, but Chen says they get angry e-mails from users demanding that they restore their accounts or messages.

According to Meta’s (the parent company of Facebook) Web site, it’s universal practice for Facebook to collaborate with ICFN-certified local groups.

Both organizations are mostly reactionary, having just enough resources to vet information submitted by users through chatbots. Chen says that while they can mostly determine the source of misinformation, they aren’t able to thoroughly investigate its ultimate origins and who’s benefiting from it financially or politically.

Although Chen thinks there needs to be some sort of government regulation (the proposed digital intermediary service act was suspended in September), she doesn’t think people who spread misinformation should be fined.

“It may not be malicious,” Chen says. “Forwarding messages fulfills a social need. Perhaps the information answered some questions this person has had for a long time, and they want to let others know about this discovery right away. Maybe this person just lacks media literacy, so why would you punish them?”

EDUCATING, CONVINCING

Yeh believes that encouraging media literacy is still the only way to get people into the habit of fact checking before they share.

“You don’t have to believe us, but at least look at a few more sources,” Chen says.

While the nation’s 2019 education curriculum guidelines include media literacy, teachers decide how it is taught. Some teachers use TFCC material, Chen says, and many have visited them to discuss how they can incorporate media literacy into their courses. But that depends on how motivated the teacher is.

At home, Chen says gentle persuasion with loved ones who are susceptible to believing and spreading fake news is more effective than aggressively questioning why they believe it.

MyGoPen has a mantra for trying to convince someone: be tactful when pointing out someone is wrong, exaggerate your praise if someone did the right thing and be very patient when communicating.

“Go about it as if you were teaching a child,” Lee says. “Also, start from disinformation that is less politically sensitive, and then slowly build up the channel of communication from there.”

Top 10 fake news from Dec. 5 to Dec. 11

1. Newly elected Chiayi city councilor puts on sexy car wash to thank voters

Debunked — the video was from an event in Thailand

2. Chiayi city councilor thanks voters by publicly baring her breasts

Debunked — the photo is from the Pride Parade in Kaohsiung

3. Lunar New Year traffic checks and clampdowns start today

Debunked — they start on Jan. 1

4. Increased fines for turning right on red lights and drunk driving start on Dec. 20

Debunked — this news has been in circulation since 2019 and there have been no recent changes to fines

5. The Government will soon start fining scooter drivers who cross the white line at crosswalks

Debunked — old news

6. China will start checking and cleaning Line accounts from 3am to 7am, so don’t send any photos or links to groups during that time

Debunked — Line is blocked in China, and people must first join LINE groups to see the messages

7. New XBB COVID variant has few symptoms yet is five times as potent ad Delta with higher mortality rates

Debunked — XBB features standard symptoms such as coughing and fever, and there is no evidence that the mortality rate is higher

8. The temperature will dip below 10 degrees Celsius from Dec. 5 to Dec. 9

Debunked — this was from last year’s weather forecast

9. Wearing hats can prevent strokes in cold weather

Partially true— there is no evidence linking heat dissipating from one’s head to strokes, but keeping warm in general does help high-risk people

10. Eating the pickled ginger in bento boxes or sushi will cause kidney failure due to unscrupulous factories adding calcium chloride to it

Debunked — this is based on a single incident in 2014, and although people with kidney issues should not eat too much pickled ginger, it’s unlikely to lead to kidney failure

Nine Taiwanese nervously stand on an observation platform at Tokyo’s Haneda International Airport. It’s 9:20am on March 27, 1968, and they are awaiting the arrival of Liu Wen-ching (柳文卿), who is about to be deported back to Taiwan where he faces possible execution for his independence activities. As he is removed from a minibus, a tenth activist, Dai Tian-chao (戴天昭), jumps out of his hiding place and attacks the immigration officials — the nine other activists in tow — while urging Liu to make a run for it. But he’s pinned to the ground. Amid the commotion, Liu tries to

The slashing of the government’s proposed budget by the two China-aligned parties in the legislature, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), has apparently resulted in blowback from the US. On the recent junket to US President Donald Trump’s inauguration, KMT legislators reported that they were confronted by US officials and congressmen angered at the cuts to the defense budget. The United Daily News (UDN), the longtime KMT party paper, now KMT-aligned media, responded to US anger by blaming the foreign media. Its regular column, the Cold Eye Collection (冷眼集), attacked the international media last month in

A pig’s head sits atop a shelf, tufts of blonde hair sprouting from its taut scalp. Opposite, its chalky, wrinkled heart glows red in a bubbling vat of liquid, locks of thick dark hair and teeth scattered below. A giant screen shows the pig draped in a hospital gown. Is it dead? A surgeon inserts human teeth implants, then hair implants — beautifying the horrifyingly human-like animal. Chang Chen-shen (張辰申) calls Incarnation Project: Deviation Lovers “a satirical self-criticism, a critique on the fact that throughout our lives we’ve been instilled with ideas and things that don’t belong to us.” Chang

Feb. 10 to Feb. 16 More than three decades after penning the iconic High Green Mountains (高山青), a frail Teng Yu-ping (鄧禹平) finally visited the verdant peaks and blue streams of Alishan described in the lyrics. Often mistaken as an indigenous folk song, it was actually created in 1949 by Chinese filmmakers while shooting a scene for the movie Happenings in Alishan (阿里山風雲) in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投), recounts director Chang Ying (張英) in the 1999 book, Chang Ying’s Contributions to Taiwanese Cinema and Theater (打鑼三響包得行: 張英對台灣影劇的貢獻). The team was meant to return to China after filming, but