In summertime, Taiwan’s cities become so hot that the amount of electricity used by air-conditioning units threatens the stability of the power grid. Because of the heat, residents with cardiovascular or respiratory diseases are at greater risk of dying. Rates of depression and suicide creep upward, and even healthy citizens dread going outdoors.

Such extreme temperatures are caused by the urban heat island effect, which results in city centers becoming significantly warmer than suburban and rural areas.

The phenomenon is well understood. It was first written about more than 200 years, and the term “urban heat island” (UHI) has been around for almost a century.

Photo: Steven Crook

THE UHI EFFECT

The difference in temperature is often so obvious there’s no need to look at a thermometer.

Taiwanese who commute from rural townships by motorcycle can notice that, as soon as they leave the built-up zone on the ride home, it gets a bit cooler. This is especially true after sunset, because sun-baked concrete and asphalt surfaces take hours to cool down.

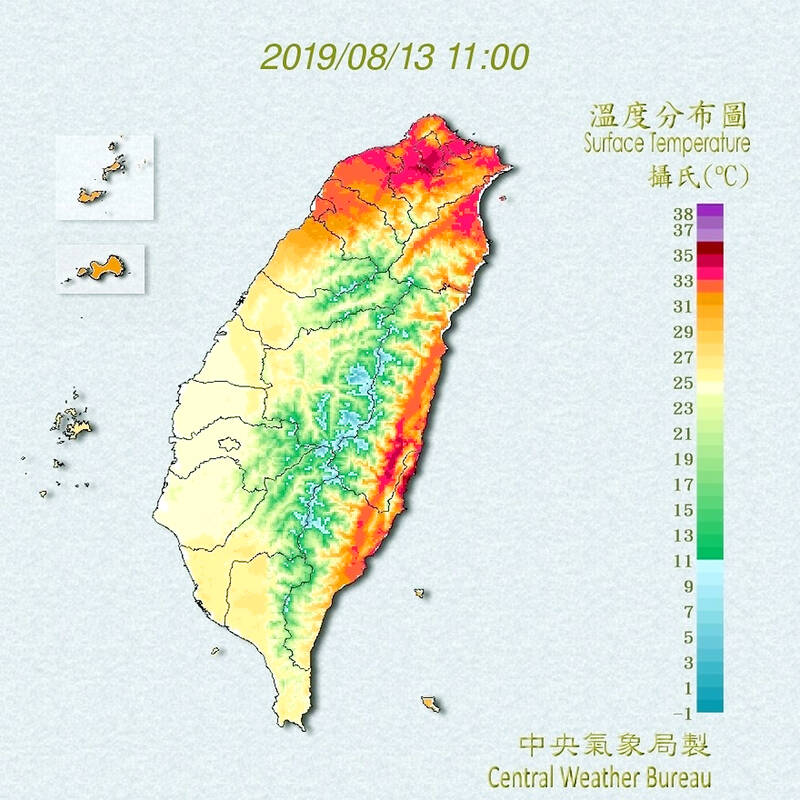

Photo courtesy of the Central Weather Bureau

Central Weather Bureau (CWB) statistics show that, in Taipei, the annual average number of high-temperature nights (when the mercury lingers above 25 degrees Celsius) was 81 between 1991 to 2000, 97.5 from 2001 to 2010, and 109.9 in the 2011-2018 period.

A study based on data from the summer of 2012, when Taipei suffered severe heat waves, concluded that, during the day, the city’s center was as much as 6.87 degrees Celsius hotter than its periphery. In Kaohsiung and Tainan, the UHI effect is typically around 3 degrees Celsius. In Taichung and Taoyuan, it’s less pronounced.

Not surprisingly, there’s a correlation between heat islands and power bills. According to Why is Summer in the City Getting Hotter and Hotter? (都市的夏天為什麼愈來愈熱?), a book published last year by academic Lin Tzu-ping (林子平), keeping a 41-ping (坪) / 135m2 house in central Taipei comfortably cool costs approximately NT$6,400 per year more than it does for an identical house in the districts of Muzha (木柵) or Guandu (關渡).

Photo: CNA

Policymakers — as well as scholars like Lin — are now paying more attention to UHIs, and not just because the consequences for human health have begun to sink in.

Sweltering cities make meeting carbon-emission goals even more difficult. As urban temperatures rise, greater electricity consumption is almost inevitable, even though new air-conditioners are more efficient than old units. Despite the government’s late-in-the-day push for renewables, Taiwan could well end up burning even more fossil fuel.

The UHI problem is exacerbated by high population density and building practices. Not much can be done about the number of people in Taiwan and the fact that most of them need to live in or near a major city. But, as an article in CommonWealth magazine in June last year puts it, “architectural design is an accomplice to rising temperatures.”

Lin, a professor in the Department of Architecture and head of the Building and Climate Research Laboratory (BCLab) at National Cheng Kung University, oversees ongoing research on Taiwan’s UHIs.

In recent years, the BCLab has connected around 250 microclimate measuring stations in the six special municipalities to form a real-time temperature-measuring network.

Lin and his team have concluded that, in Taipei, Wanhua (萬華) and Datong (大同) are the districts most susceptible to UHI impact. In his book, Lin explains that these places — along with Banqiao (板橋), Sanchong (三重) and Yonghe (永和) districts in New Taipei City — all lie at the lowest part of the Taipei Basin, and thus lack the natural cooling that slightly higher settlements enjoy.

What’s more, in old neighborhoods such as Wanhua, the density of buildings is exceptionally high, so there’s less air circulation. This means not only a lack of refreshing breezes for people out on the streets (and homebodies who open their windows), but also that sun-warmed asphalt and concrete take longer to cool down.

BCLab’s measurement work makes it possible to identify precise UHI blackspots, and to advise local governments on planning decisions that could open up heat-mitigating “pathways for wind.”

In a 2020 paper published in Sustainability, scholars at the Department of Landscape Architecture, National Chiayi University, noted that UHIs are heavily influenced by urban geometry (how buildings are shaped and grouped) and the type of land cover (how much of a given area is buildings, roads, farmland, woodland or water).

Because changing the urban geometry of a mature neighborhood is difficult and costly, they focused on land-cover strategies that can mitigate the UHI effect: Planting trees along streets; “greening” rooftops; and replacing concrete and asphalt surfaces with permeable, water-retaining paving.

STRATEGIES TO REDUCE HEAT

The researchers didn’t actually plant trees or dig up sidewalks. Instead, they used software that can predict microclimatic conditions by simulating the interaction of surfaces, plants and air, to create what-if scenarios for parts of central Kaohsiung. The baseline meteorological environment was calculated by referring to summer days between 2014 and 2019 when the CWB’s weather station in Kaohsiung’s Sinsing District (新興) recorded temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius.

Five strategies were tested and compared to the baseline. The first imagined the adoption of permeable pavement. The second increased the green coverage ratio of the street to 60 percent. The third combined the first and second interventions. The fourth increased green coverage in parks to 80 percent, on top of the first and second interventions. The fifth included everything done in the fourth, plus 100-percent green coverage on the roofs of public buildings.

Not surprisingly, the fifth approach had the greatest effect. According to the simulations, those measures could cool an area by an average of 2 degrees Celsius.

Cooling isn’t the only reason why the authorities should plant more trees in built-up areas. As discussed in a previous column (“The importance of throwing shade,” April 7, 2021), there’s evidence that increased urban tree cover improves residents’ mental health.

A 15-month-long field test in Taiwan’s capital, described in a 2019 paper in the journal Water, suggests that changing the materials we use to build roads and sidewalks could help blunt rising temperatures.

For the experiment, which was funded by Taipei City Government, one stretch of porous asphalt (PA) bicycle lane, and another of permeable interlocking concrete brick (PICB) pedestrian walkway, were monitored for surface temperatures at 10-minute intervals during storm events and after long dry periods.

Both absorbed significantly less heat than conventional surfaces. In heavy rain, PICB was up to 6.6 degrees Celsius cooler than ordinary concrete. During dry spells, PA was as much as 14.4 degrees Celsius cooler than standard asphalt.

There’s a catch, of course: Laying porous pavement is 10 to 15 percent more expensive than traditional pavement, the paper notes.

Some researchers have stressed the importance of enhancing buildings’ albedo (the percentage of total solar radiation they reflect rather than absorb). This can be done by applying special paints to flat rooftops. These are widely used in Australia, but few homeowners in Taiwan even know that such products exist.

At street level, selecting trees with greater leaf-area density, in order to block more sunshine, could help.

Vehicles generate a lot of heat, so any measure that keeps cars and motorcycles out of urban centers would be a step in the right direction.

Distributed district cooling (DDC) systems, which work by pumping chilled water through pipes, already exist in Paris, Tokyo, Chicago and other cities.

An April 18 report in The Strait Times explains the thinking behind a seven-building retrofitting project in Singapore: “District cooling is more energy-efficient as the system reaps the benefits of economies of scale by sharing chiller capacity… Such technology is being implemented worldwide…to reduce carbon footprint.”

Moreover, because they cool and store water before it’s needed, DDC systems lessen the risk of the grid being overwhelmed during the hottest part of the day.

The campuses of some local tech companies use DDC networks, but so far this technology hasn’t been incorporated into any public infrastructure projects.

Perhaps the authorities are waiting until Taiwan’s cities get even hotter.

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she