Before she starts singing, Vivi Tan (陳映璇) asks the crowd of mostly children: “Do any of you understand Taigi?” Only a few raise their hands, but they sing along when she teaches them how to say “good morning” in the night’s first number, Gau tsa.

Taigi is the transliteration of Hoklo (better known as Taiwanese). The tune is an original by Tang Lek-hian (董力玄), cofounder of Taigi Road (牽囡仔e手行台語e路), a support and activity group for parents who are teaching the language to their children. Tan and her husband Iunn A-ian (楊晉淵), a professional musician, have been participating in the group for a few years.

Brought to Taiwan 400 years ago by Han settlers from Fujian Province, China, Taigi was once the most-spoken language in Taiwan, but its usage has been in decline since the 1930s, first due to the Japanese kominka policy in which Taiwanese had to learn Japanese. Then came decades of linguistic oppression under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), which successfully made Mandarin Chinese the dominant language in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Taigi Lok

From the 1950s to the 1990s, children were punished in school for speaking Taigi, which was branded along with other local tongues as uncultured and vulgar. Many who grew up during that time did not teach their children, who, like Tan and Iunn, are now having children of their own.

“My Taigi was quite poor,” Tan says.

Iunn, who regularly speaks it with his parents, still signed up for Taigi lessons upon finding out they were expecting.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Despite recent efforts to revive and promote the nation’s various “mother tongues,” Mandarin’s dominance continues to grow in the younger generation. According to government census data from 2020, 92.1 percent of six to 14-year-olds used Mandarin as their primary language, compared to 77.5 percent of 34-45-year-olds and 28 percent of those above 65. It has especially declined around the capital region, with only 15.4 percent of Taipei citizens primarily speaking Taigi, compared to 43.2 percent in Kaohsiung.

Although born to Taigi-speaking parents, Tan and Iunn solely communicated with each other in Mandarin until they decided to pass on Taigi to their children.

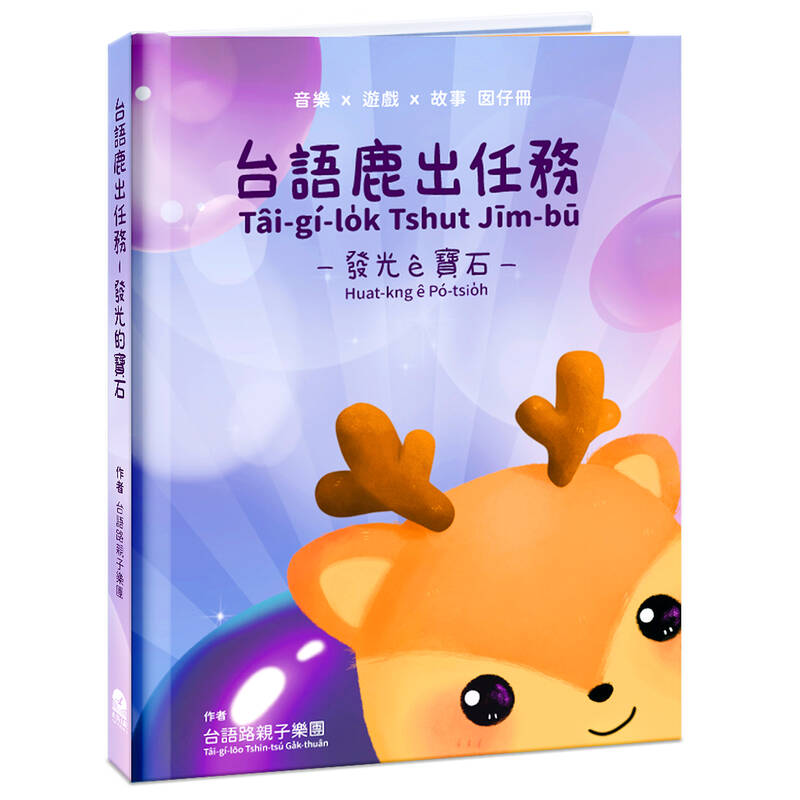

Taigi Road doesn’t just collaborate musically. Its members pool their resources to organize learning experiences such as field trips and create compelling teaching material. The professionally produced songs are the basis for the group’s sing-a-long activity book Tai-gi Lok (台語鹿出任務:發光的寶石), which just concluded its online fundraising campaign, where they nearly tripled their goal.

Photo courtesy of Taigi Lok

“Nowadays, you need to persevere if you want your child to be able to speak their mother tongue,” Tang says. “Parents need to support each other, and we also have to push the government to introduce changes.”

INSPIRED BY NEW LIFE

Like many families in her generation, Tang’s grandparents only spoke Taigi, so she spent her early childhood immersed in it. However, Mandarin became her main language soon after she started school, and she says her Taigi-language ability stayed at a child’s level.

Photo courtesy of Taigi Lok

But it was harder to get her and her husband’s parents — who are fluent in Taigi — to start speaking it with her three children. They were the generation who got punished in school for speaking local languages instead of Mandarin, and many are still afraid to use it.

“My mother-in-law received higher education and worked as a teacher,” she says. “It took her months to adjust to my request to start speaking Taigi. When she goes out on her own, she still uses Mandarin — she feels that people will judge her,” Tang says.

Tang didn’t understand the political and social causes behind language loss and the importance of linguistic preservation until she started educating her own children.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Tang also learned about the mental and developmental benefits of bilingualism. For example, it’s easier for children to learn other languages if they’re raised bilingually; regularly using two languages also keeps the mind of elderly people more active.

Iunn also realized the importance of passing on one’s mother language after he found out he was going to be a father.

“We are doing this because of the kids,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Taigi Lok

CREATING RESOURCES

Tang says she started Taigi Road to meet other parents who were trying to maintain Taigi-speaking households. They soon expanded in number and began organizing weekly trips and fun educational experiences for the children.

“We needed to create something that could capture the children’s imagination as much as Mandarin and English children’s songs do,” Tang says.

Tai-gi Lok offers activities for a wide range of ages and levels, and the songs are also suitable for families who speak Mandarin, Tang says.

“We also encourage parents to use the language at home,” Tang says. “It’s a waste if you don’t use something you’ve already learned.”

DOES IT WORK?

Tang’s children are still young, the oldest being 7, but once they spend more time in the education system, they’ll be exposed to mostly Mandarin — and English. They do have one period of Taigi class per week, but it’s not nearly enough, and is meant for those children whose family don’t speak it at home.

Some children have lost the ability to speak Taigi as they’ve grown older — one issue among many that are addressed in weekly seminars.

Ultimately, the key is using the language as much as possible, especially outside the home, she says.

“They’ll definitely meet fewer Taigi speakers as they get older, but we want to show our kids that other people do speak the language, including some of their friends,” Tang says.

For more information, visit: facebook.com/taigilok.

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

For the past century, Changhua has existed in Taichung’s shadow. These days, Changhua City has a population of 223,000, compared to well over two million for the urban core of Taichung. For most of the 1684-1895 period, when Taiwan belonged to the Qing Empire, the position was reversed. Changhua County covered much of what’s now Taichung and even part of modern-day Miaoli County. This prominence is why the county seat has one of Taiwan’s most impressive Confucius temples (founded in 1726) and appeals strongly to history enthusiasts. This article looks at a trio of shrines in Changhua City that few sightseers visit.