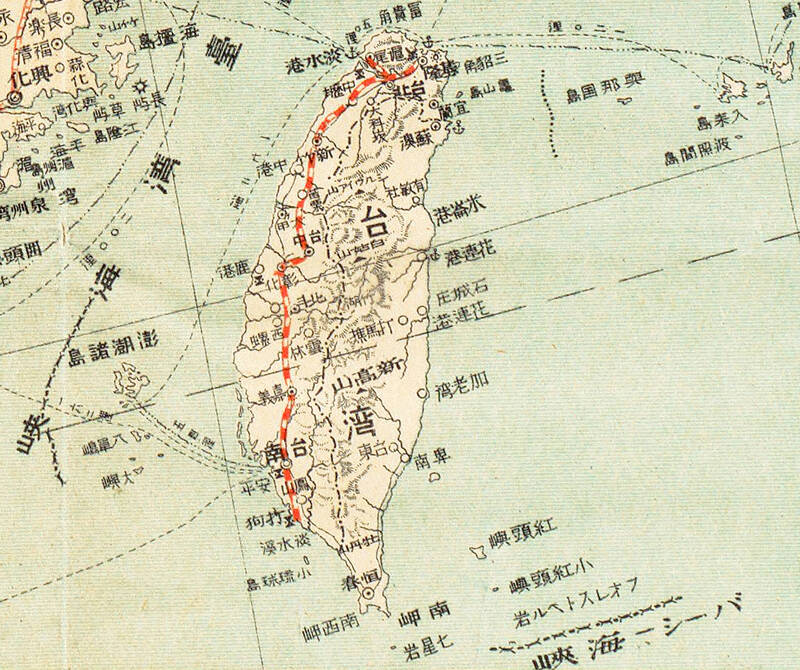

After Taiwan became a Japanese colony in 1895 the government of Japan, always interested in proposals to increase its economic independence, began exploring the possibility of growing tropical drug plants on Taiwan.

The leader in such experiments was Hoshi pharmaceuticals, founded in the second decade of the 20th century. In the 1920s and 1930s, Hoshi was a leader in cinchona cultivation in Taiwan, and of cocaine, then used as an anesthetic.

TAIWAN’S COCAINE PRODUCTION

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Hoshi’s cocaine production grew quite large, and after better anesthetics were invented in the 1920s, Japan’s problem became disposing of all its production. Taiwan’s production was particularly useful. The coca leaf produced in Chiayi had twice the alkaloids of the Peruvian varieties (South America’s modern dominance of the cocaine trade is largely a historical accident of German chemistry, the US victory in World War II and Japanese destruction of Dutch coca plantations in Java during its brief occupation there) and it was far cheaper to ship it to Asian destinations than Peru.

How humans stimulate themselves is a product of politics and culture. In Taiwan, alcohol and betel nut, so destructive, are completely legal, while marijuana remains forbidden. Imagine today going down to Chiayi in some alternate universe to tour the endless plantations of high-quality coca or marijuana rather than betel nut trees and tea.

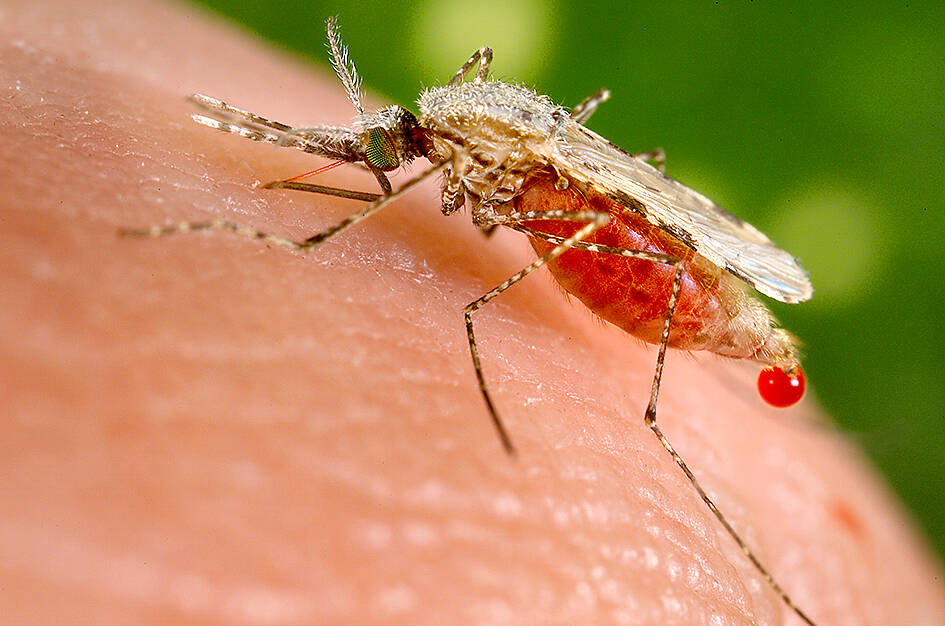

MALARIA

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Cinchona became another key tropical product explored by Hoshi. The tree’s bark had long been recognized in Europe as a medicine against malaria, a problem until modern pesticide campaigns and swamp drainage wiped it out in most developed countries.

Westerners often associate malaria with the modern tropics, but in the US especially before the 1880s it was deadly, accounting for roughly 4.5 percent of all child deaths, and a major drag on the economy, just as it is today in malarial regions. Even in the brutal Little Ice Age in the 17th century, malaria was common in London and the surrounding region. Shakespeare refers to it in eight of his plays.

With Japan colonizing Korea, Taiwan and Manchuria, with plans to expand further south, malaria treatments became an urgent security issue. Into the 20th century it was the number three killer in Taiwan, after cholera and plague, and as late as 1940 it sent 1.7 million people to local hospitals and clinics. It wreaked havoc on Japanese soldiers in Korea, and a milder strain plagued Chinese mine workers in Manchuria, reducing coal output.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

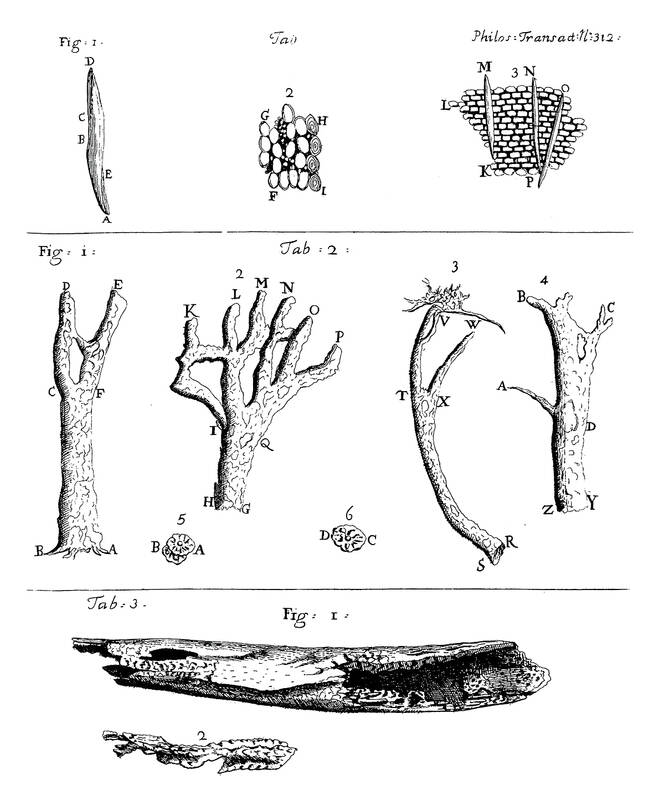

CINCHONA PRODUCTION

During Japan’s 1874 invasion of southern Taiwan, the army’s medical teams reported nearly 8,000 cases of infectious disease, roughly 4,500 of which were malaria. Cinchona had been introduced into Japan in 1876, but cultivation failed, and an attempt to grow it in Bonin Islands foundered. Given the empire’s problems with malaria, growing cinchona in Taiwan looked like a no-brainer.

As scholars have noted, Hoshi saw the western monopoly on cinchona as a threat to Japan. Japanese thinkers also proposed cultivation of cinchona as a way to solve what the Japanese saw as “the aborigine problem” — the problem of imposing Japanese imperial power on aborigines defending their lands.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Japanese scientists argued that Taiwan’s indigenous population needed to be moved away from slash and burn techniques, and that cultivating cinchona would create a more “sustainable” way of life. Of course, they also argued that since the indigenous population had no concept of land ownership, they didn’t own the mountain lands.

According to scholars Heather Rogers and Kelly Chan (“Mapping Ecological Imperialism: A Digital Environmental Humanities Approach to Japan’s Colonization of Taiwan,” Material Culture Review, Fall, 2022), Japanese thinkers saw this as a humanitarian and cooperative approach under which indigenous communities would be integrated into the colonial economy through cinchona cultivation on plantations and receive food and low-level agricultural educations.

“This dynamic thus placed agriculture at the center of the structure of colonial relations,” Rogers and Chan observe. In the form of indentured servitude for indigenous communities, I might add.

Successful cultivation of cinchona began in 1922. Hoshi established plantations in Taitung and in Kaohsiung, with other companies and private individuals creating them elsewhere in Taiwan. All located on what had been indigenous lands, they ran on indigenous labor. By 1934 Hoshi had produced quinine from the bark, thus creating an integrated supply entirely within the confines of the empire.

In 1937 Japan invaded China, and demand for quinine became urgent. The government directed Japanese in Taiwan to plant 8,000 acres of cinchona, for a production goal of 2,400 tons of bark (one-fourth the production of Dutch Java). Though there are few surviving records, scholar Ku Ya-wen (顧雅文) has produced some tentative maps of their locations, all largely at altitudes of over 1,000 meters. Ku observes that wartime demand meant that Taiwan, once more or less self-sufficient in quinine, developed shortages.

One of the features of science-based medicines is that they are quickly uptaken into traditional and alternative systems and extolled for their assumed amazing properties. In Japan cinchona bark became a treatment for all sorts of ailments, from “hysteria” to impotence (impotence is apparently the most traditional of ailments), and enjoyed a kind of vogue in the 1930s.

WORLD WAR II AND BEYOND

After Germany ignited the second world war in Europe it became almost impossible for Japan to get hold of anti-malarials like quinine, atabrine and plasmoquinine from Germany. The occupation of Java with its immense plantations of cinchona, responsible for roughly 90 percent of world bark production, eased the situation briefly, but shipments to Japan fell off as the war progressed.

Quinine remained the most important anti-malarial until other drugs took its place in the 1940s, and colonial production of cinchona was less important. In his book How to Hide an Empire, Daniel Immerwhar observes that the development of new technologies such as plastics and artificial rubber made colonies obsolete. No longer did they produce unique raw materials.

Taiwan’s next colonizing power, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), as George Kerr observed in Formosa Betrayed, seized the Japanese stocks of raw opium and coca leaves.

“The narcotics industry as a State concern had been always a source of great friction between Formosans and the Japanese administration,” he wrote.

According to Ker, in the mid-1930s the Japanese, even under figures doctored to avoid attracting attention, admitted to holding over 4,000 tons of coca leaves and 125 metric tons of cocaine.

A decade later Chen Yi (陳儀), whom Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) had appointed to run Taiwan, said that the government had recovered only 9,700 pounds of opium and “a small amount” of cocaine. Chen Yi also stated that production of cocaine and coca would cease, and that he was taking over the coca plantations.

According to Kerr, the US government reported in 1949 that it had received no information from the KMT government on the production or inventories of such narcotics in Taiwan.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has