This is the type of movie that makes people hate journalists. Not only does Chang Hsiao-chuan (張孝全) effortlessly play the stereotypical dogged, slimy reporter who discards any ethical boundaries to get a story, he habitually manipulates facts to boost online views for his floundering news program.

But the grim truth for the industry, as shown in an exaggerated manner in The Post-Truth World (罪後真相) is that clicks rule the news these days, and viewers should not entirely trust the information being presented. Neither should the journalists themselves.

This biting critique of Taiwan’s increasingly sensationalist media landscape is smartly packaged as a glossy murder-mystery thriller, boosted with celebrity cameos. It’s slick and entertaining enough, but it’s the understated complexity of the main characters that makes the film thought-provoking.

Photos courtesy of Vie Vision Pictures

Despite his flaws and questionable behavior, Chang’s character, Brother Li-min, somehow still manages to come off as a sympathetic hero. He seems to want to do the right thing, especially at the behest of his late wife, who was an award-winning investigative journalist, but also faces immense pressure from his boss (who at the same time makes righteous comments about delivering fair and balanced news) to get views.

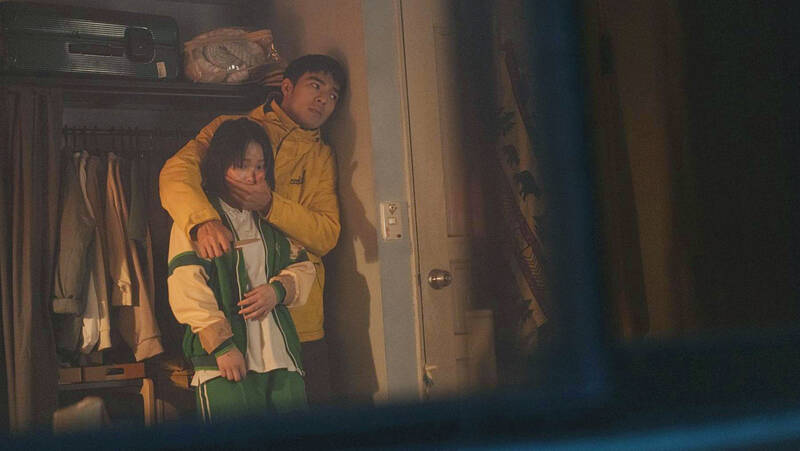

Li-min’s precocious teenage daughter Chen-chen, played with nuance by last year’s Golden Horse best newcomer Caitlin Fang (方郁婷), basically takes care of him and is often put in danger due to his recklessness. Her innocent support of her father’s endeavors drives the point of the movie home: she knows that Li-min twists the truth in his videos, but having grown up in the age of social media, perhaps that is the norm. As long as her father’s clips go viral, she’s happy, and Li-min doesn’t seem bothered by this fact.

In his desperate bid to save his program, Li-min inadvertently becomes involved with Chang Cheng-yi (Edward Chen, 陳昊森), a once-promising high school baseball player who spent seven years in prison for murdering his girlfriend. The media paints him as a cold-blooded monster, with YouTubers and other social media creators adding to the fire, leading to his condemnation despite insisting that he is innocent. Chen flaunts his acting chops, deftly portraying the formerly naive, bright-eyed young man now driven by hatred and haunted by his past.

Photo courtesy of Vie Vision Pictures

Li-min believes that Cheng-yi did not commit the murder, and he also believes that overturning the conviction will get him the one million subscribers he needs to avoid cancellation. It’s important to show viewers that the two motives are not mutually exclusive, and not everything about the industry is so black and white.

Li-min soon discovers that the case is more closely tied to people around him than he had imagined, adding to the urgency of his quest and giving it new meaning. What ensues is a pretty standard trope where he goes rogue and helps Cheng-yi, who has escaped from prison and inexplicably manages to elude the police, though he maintains a high profile.

Saying any more would spoil the rest of the film, which is thought provoking with just the right amount of suspense, twists and very few plot holes. It’s not just the media that cannot be trusted, and even what appears to be the “truth” of the case is repeatedly overturned until the very end.

Photo courtesy of Vie Vision Pictures

What happens when Li-min eventually solves the mystery, only to realize that revealing it may do more harm than good? For a movie of this genre, the questions posed are surprisingly complex.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

Artifacts found at archeological sites in France and Spain along the Bay of Biscay shoreline show that humans have been crafting tools from whale bones since more than 20,000 years ago, illustrating anew the resourcefulness of prehistoric people. The tools, primarily hunting implements such as projectile points, were fashioned from the bones of at least five species of large whales, the researchers said. Bones from sperm whales were the most abundant, followed by fin whales, gray whales, right or bowhead whales — two species indistinguishable with the analytical method used in the study — and blue whales. With seafaring capabilities by humans