Oct. 3 to Oct. 9

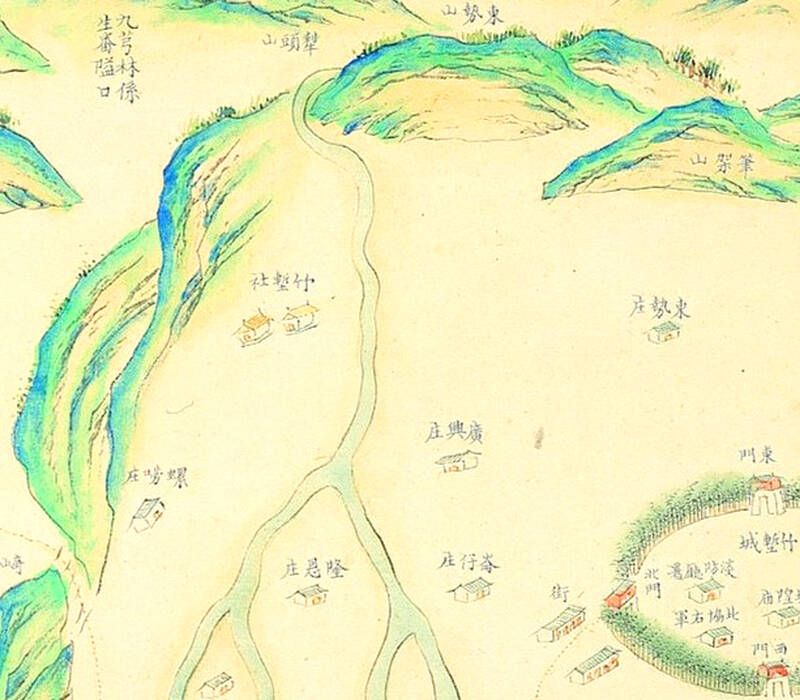

Wang Shih-chieh (王世傑) could not forget the fertile plains he saw on his trip north. He first passed by in 1682 while delivering food supplies to Kingdom of Tungning troops, who were suppressing indigenous unrest in northern Taiwan.

More than a decade later, the Kinmen native returned with over 180 settlers from his home village, establishing a prosperous settlement that became today’s Hsinchu City. The place they first set up camp is at Lane 36 Dongqian Street (東前街), which is designated Hsinchu’s first street and the birthplace of the city. The sign says they arrived in either 1691, 1701, 1711 or 1718.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wang constructed the Longen Canal (隆恩圳), one of three ancient waterways in town, and several temples that still stand today. Many sources state that he died on Oct. 5, 1721 during a trip home, but some maintain that he was beheaded by an indigenous robber on the same date while inspecting the canal. In any event, his relatives were said to have made a head from gold, attached it to the body and sent it back home to rest in the ancestral grave.

Obviously there were indigenous people living in this area already, but the sign doesn’t mention them at all. A Hsinchu Bureau of Cultural Affairs document notes that Wang traded with them and established boundaries between the two groups, and farmed initially on abandoned indigenous land.

Who were these original inhabitants, what happened to them and how exactly did Wang die? Taiwan in Time investigates.

Photo: Hung Mei-hsiu, Taipei Times

STRONGMAN

An 1995 article in Hsinchu Journal of History (竹塹文獻) by Wang’s ninth-generation descendent Wang Chia-tsan (王家燦) confirms that Wang was born in 1624 in Jincheng (金城) in today’s Kinmen. The warlord and Ming loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, or Koxinga) was based in Kinmen before dislodging the Dutch from Taiwan, and Wang joined his army at some point. He was in charge of protecting the grain supplies for Cheng’s Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning.

Wang was rewarded with cultivation rights after successfully delivering food supplies to the troops in 1682, and he chose the piece of fertile land he saw on the way. He returned to Kinmen and began recruiting settlers, but the Qing Dynasty’s annexation of Taiwan in 1683 delayed his plans. They arrived sometime between 1691 and 1718, and set up basic huts along “Hsinchu’s first street.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This account notes that relations with indigenous Taokas were peaceful, noting that the areas indigenous inhabitants usually cultivated land for a few years before abandoning it and moving on, and these were the lands that Wang’s people initially farmed on.

In the same publication, Chang Te-nan (張德南) discusses the settlement process in more detail. Even though Taiwan was under Qing rule, the closest government post was in Tamsui, and they had little jurisdiction over the hunting grounds for the Taokas in Hsinchu. As a result, Han settlers fended for themselves, with Wang acting as a strongman who maintained order and protected the settlement.

These strongmen either applied for cultivation rights from the government or purchased land directly from the indigenous and rented it to the settlers. The operation required considerable funds and strong leadership skills, and Wang’s empire continued to expand under his descendants.

Photo: Hung Mei-hsiu, Taipei Times

HOW DID WANG DIE?

Both articles maintain that Wang died from natural causes during a visit home. So do at least three other historic sources, including one copy of the Wang family genealogy book. Chang revisits the issue of Wang’s death in a 2018 article.

The source of Wang being murdered comes from 13th generation descendant Wang Shih-kun (王世焜), who manages his ancestor’s old residence in Kinmen. He notes that Wang’s grave has been called the “golden head ancestral tomb” by the family for generations.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The story matches one written by Lan Ting-yuan (藍鼎元), a Qing military officer who came to Taiwan to suppress a peasant rebellion led by Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴) in 1721, the same year Wang died. While passing through Hsinchu, Lan noticed that the streets were especially empty. He learned it was because someone had been beheaded by an indigenous robber and residents were afraid to leave their homes.

Chang thinks this story apocryphal; indigenous attacks were not uncommon in those days, and there had been no record of this story in Kinmen until the government began researching Wang’s tomb and residence in 2005. Furthermore, Chang argues that traditional bone-pickers (撿骨師) called the remains “golden bones” (金骨) out of reverence, and such reburials were often called “golden auspicious burials” (黃金吉葬).

FALL OF THE TAOKAS

The Taokas were the dominant group in the area, and their territory, commonly referred to as Jhuchien (竹塹社, Tek-kham in Hoklo), was called Pocael by the Dutch. Jhuchien was also one of the names of the area’s walled city until it was officially renamed Hsinchu in the 1870s.

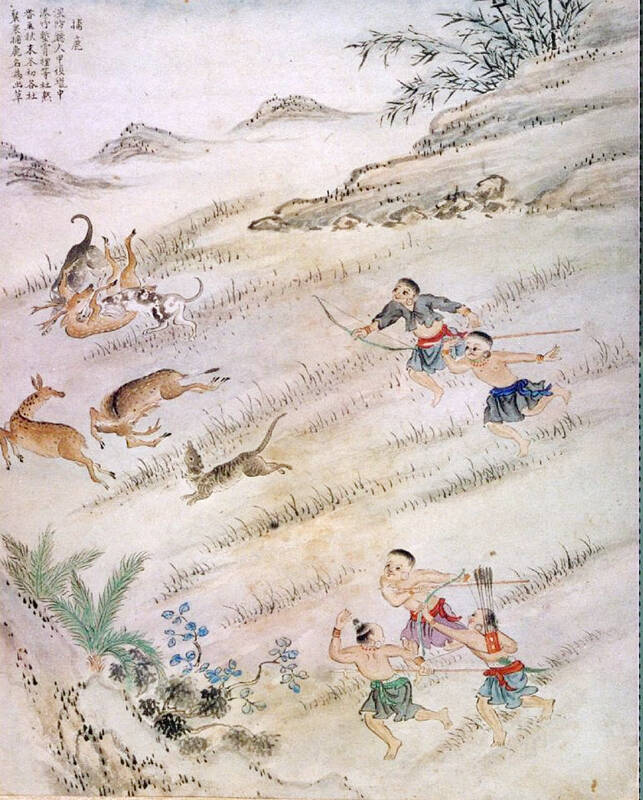

According to local accounts, the Taokas got along with the early settlers and often farmed side by side. But farming was not their expertise as they were previously hunters and fishers, and they quickly declined in power.

After accepting Qing rule around 1700, the Taokas were subjected to heavy taxes, which they paid by selling deer skins. This led to overhunting, and in 1715, Qing official Ruan Tsai-wen (阮蔡文) wrote a poem about the dwindling deer supply and how more than half of the Taokas traditional hunting grounds were now occupied by Han farmers. He described how the Taokas struggled to match Han productivity, and some were so poor they couldn’t even start a family.

Many opted to rent or sell their land to the settlers instead, but after the tenants grew prosperous enough, they often seized the land as their own. Some Taokas were able to get by and acculturate to this new life, and continued to live in small settlements while maintaining their language and customs.

In 1724, the Qing emperor allowed people to settle in the Hsinchu area en masse, later permitting them to bring their wives and children. By the mid-1700s, Han settlers had completely overrun the area.

After finally reducing their taxes in 1737, the Qing established in 1750 a Taokas-only reserve for them to hunt and farm. They also gave them special land renting rights. However, they accelerated their cultural loss by ordering them to adopt Qing hairstyles and dress and giving them one of seven Chinese surnames to use.

The Qing boundaries could not stop Han encroachment, however, and many opted to leave the area. Intermarriage was common, and an 1888 census shows that the 158 remaining Taokas in Jhuchien were “indistinguishable” from the Han.

The Taokas mostly registered as Han during the Japanese census, but continued to use the Taokas language during ancestor worship ceremonies until 1966, when the last person who knew the words died. Today, a Taokas cultural revival movement is based in Miaoli County’s Singang Village (新港).

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of