Nicolas Loufrani, CEO of the Smiley Company, has sharp features, and a sharper grin. I find him in his London office wearing grey pin-striped dungarees, beaming energetically, clutching a poster that says: “Take the time to smile.”

Around him, the room fizzes with iterations of the icon — you know the one. Fluorescent lights in the shape of that unmistakably simple, upbeat expression. Clothing, homeware, bottles of prosecco… all stamped with it. A basketball net boasts a smiling backboard to hurl a ball at. A bowl of fruit? Also happy. I spot a small framed print of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, her face replaced with a yellow smirk. Nothing is off limits. The Smiley Company puts smileys on things. Last year it sold US$486 million worth of products.

Loufrani, 50, greets me with fast-talk and a French accent, steering me between desks to a small meeting room. We brush past employees in smiley-smattered harem pants, bearing MacBooks slapped with smiley stickers. They smile politely. We smile back. Across the open-plan room a fashionable young workforce busies itself at computers. Every season Loufrani and his team come up with hundreds of new concepts for smiley-based products and promotions and pitch them to brands. The Smiley Company owns the rights to the image in over 100 countries.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yes, the smiley — at least, this particular version of it — is a trademarked image. Want to use it? You gotta pay.

SMILEY ‘MOVEMENT’

Today, the Smiley Company is ranked one of the world’s top 100 licensing businesses, with 458 licensees in 158 countries. It boasts thousands of products across 14 categories, from health and beauty to homeware. This year it celebrates its 50th anniversary, which means — you guessed it — smiles all round; 65 new partnerships and collaborations with everyone from Reebok to Karl Lagerfeld. If you’ve noticed more smileys on the high street lately, now you know why.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“We do a lot, but we also don’t do that much,” Loufrani tells me. “We’re very, very protective of our brand. We try to be creative. We try to avoid having products with just a big yellow face.”

To Loufrani, who has, in recent years, expanded the company to create a good news platform to promote charities and social enterprises, the smiley is so much more than that. It’s not simply a logo, it’s a “movement.” It stands for “defiant optimism, positive thinking, empathy, doing good.”

As the world simmers in these distinctly un-smiley times — an era marred by pandemic, the war in Ukraine and a looming global recession — Loufrani believes the Smiley Company has a lot to offer us. Smiles may be down — according to the Smiley Company’s very own smile index survey — but, thanks to a declaration by the Smiley Company, this year is set to be the “year of smiles.” They’re coming for you, whether you like it or not.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Smileys have drifted across the pop-cultural ether since the 1950s. A yellow and black one first showed its face in 1961, when it was printed on a promotional sweatshirt by the New York radio station WMCA to promote the news-talk show Good Guys. Thousands were given away.

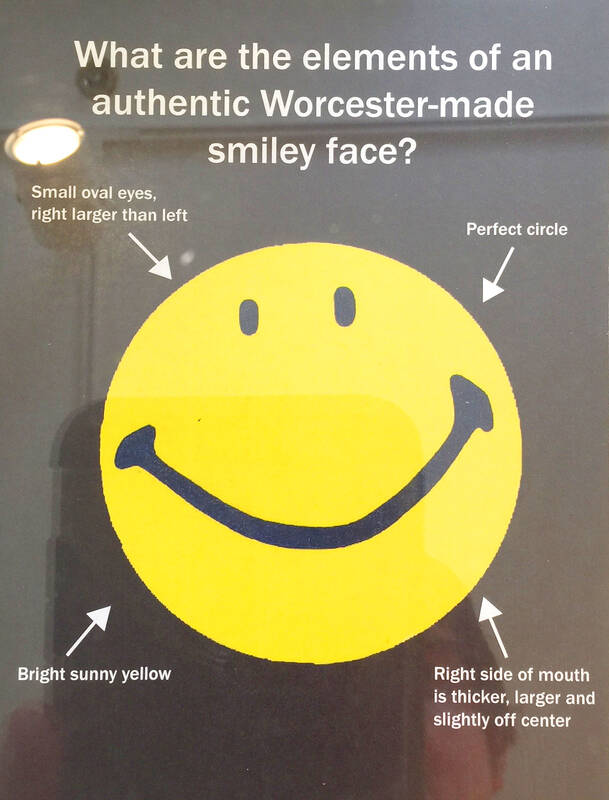

But many people credit Harvey Ball, an ad-man from Worcester, Massachusetts, for designing the smiley in its most iconic form. In 1963 Ball was hired by the State Mutual Life Assurance Company to create a smiley face icon to boost company morale. He penned his design in 10 minutes. Two dots and a flick, though not without artistic distinction — Bill Wallace, executive director of the Worcester Historical Museum, has compared the imperfect slant of its mouth to the smile of the Mona Lisa.

Ball was paid US$45. The company produced pins with a smiley face on it, and sold millions over the course of the decade, though Ball did not trademark the design. Later, in 1971, Bernard and Murray Spain, two brothers who ran a couple of Hallmark card shops in Philadelphia, spotted Ball’s design, and copyrighted a version that combined the image with the slogan: “Have a Happy Day.” In the first year alone they sold more than 50 million buttons.

The Smiley Company itself harks back to 1972, when Loufrani’s father, Franklin, became the first person to register the smiley as a trademark — taking ownership of it as a commercial logo — which he did in France. His background spanned journalism, advertising and licensing. If you wanted to market a Batman product in France during the 1960s, Franklin was your guy. Babar the Elephant merch? Speak to Franklin. Licensing — when intellectual property rights are granted to third parties for a fee or royalties — was a relatively novel concept back then and Franklin hit the jackpot the following decade.

Fed up with downbeat reporting and miserable headlines — Nixon, Vietnam, atomic war — Franklin pitched a new column to the newspaper France-Soir called Prenez le Temps de Sourire or “Take the Time to Smile,” along with a simple hand-drawn yellow smiley face to signpost good-news stories. Through his company, then called Knowledge Management International, he licensed the smiley out to other newspapers, then to other companies and products. He made a deal with Mars, which stamped smileys on Bonitos chocolate pieces, then Levi’s, which whacked it on jeans. It turned out you could put a smiley on almost anything and sell it: business boomed.

It can be difficult to imagine how such a simple icon could even be owned, but whether through genius or luck, Franklin had struck gold. The Smiley Company has fielded criticism for staking a claim to something so pervasive, but there don’t seem to be too hard feelings on Ball’s part. He died in 2001, but was “not a money-driven guy,” according to his son, Charles Ball, who told the Worcester Telegram & Gazette: “He used to say: ‘Hey, I can only eat one steak at a time, drive one car at a time.’”

To Loufrani it matters not who was first mover in the genesis of the smiley; the trademarking itself was tantamount to a creative act. “He invented it in the sense that he invented the business model of making smiley a brand,” he says. “Apple, Adidas, Puma, Fred Perry… a lot of trademarks are very simple designs. It’s not about who came up with the design, it’s about who decided to build a business out of it, to make it popular and to create values around it.”

FEELGOOD LOGO

Yet just as the use of the smiley in art, fashion and design has ebbed and flowed with social and aesthetic trends, the Smiley Company’s cycles of success have always depended on forces that exist outside it. Franklin rode these wave after wave. He was unfazed by the shifting semiotics of a once-corporate feelgood logo into something often quite subversive. It was shrewd of him not to grapple for total control over its meaning. If anything, as the smiley was woven into the tapestry of 20th-century pop culture, it boosted sales.

At first the smiley was designed to deliver a simple feelgood hit. It soon became entwined with anti-war and anti-establishment sentiments — one photograph from the 1970s shows peace protesters assembled in smiley formation. Another depicts an American soldier in Vietnam with a smiley sticker slapped on his helmet. In 1986, the artist Dave Gibbons depicted the smiley at its darkest, when he designed the artwork for Alan Moore’s comic book, Watchmen. The cover depicts the smiley with a single drop of blood trickling across its blank, yellow face.

When it came to the business of selling smileys, however, it was the birth of acid house that sent sales stratospheric. The smiley first permeated the club scene after the designer Barnzley Armitage made a run of smiley T-shirts. The DJ Danny Rampling bought one and started wearing it in Ibiza. When Rampling launched his club night, Shoom, in London, in 1987, a flyer design featured smileys raining down it like ecstasy pills. Soon the smiley was reborn as a symbol of utopianism for a new generation of ravers.

In 1989, when the UK was in the midst of the second summer of love, Franklin’s business hit peak smiley. Loufrani was a teenager at the time. He’d hear about the deals his father was making. “The numbers were quite shocking,” he tells me. “I was seeing smiley products everywhere. He made one deal with a company to produce something like 40 million badges.”

This explosion of smiley culture was short-lived. By the time Loufrani took over, in 1996, the business was, as he puts it: “burnt out… crap… meaningless. Smiley was dead.”

Rave culture had been tarnished by negative press and scaremongering about drug use. The licensing deals disappeared as quickly as they came.

“The prejudice became the excuse,” says Loufrani, “but the truth is the smiley was oversaturated. It just wasn’t something people wanted any more.”

Loufrani was determined to rebuild the family business. His approach was different to his father’s. Think “global lifestyle brand” as opposed to purveyor of flea market tat. He began trademarking the smiley around the world (a notable exception being the US, where the Smiley Company settled out of court following a 10-year legal battle with Walmart, which uses the logo in its promotions).

Loufrani also developed digital iterations of the smiley that could be licensed out, such as graphic emoticons. He tinkered with the design, and tried out new versions with a 3D effect. Franklin wasn’t convinced.

“He was shouting at me, saying, ‘Why are you changing my smiley?’ says Loufrani. “I always say: imagine you were the son of Hugh Hefner and he asked you to relaunch Playboy, and you drew Bugs Bunny. It was like that.”

The moment Loufrani really knew the Smiley Company was back on top, he tells me, was when the image featured in the opening ceremony for London’s 2012 Olympic Games. To the tune of Blue Monday, by New Order, hundreds of dancers assembled into a giant smiley, while giant inflatable smiley orbs rolled around the arena.

“Suddenly at the highest level, from the British government who were organizing the Games, the smiley was accepted as part of your heyday as a nation. It was embraced.”

So what does the smiley mean today? For Fraser Muggeridge, a graphic designer who has used the smiley in his work with artist Jeremy Deller (independently of the Smiley Company), it remains a “universal symbol” for fun.

“No one goes, ‘Oh, I don’t like the smiley face.’” he says. “It doesn’t have any negative connotations. I think it’s up there with religious iconography.”

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had