Sept. 26 to Oct. 2

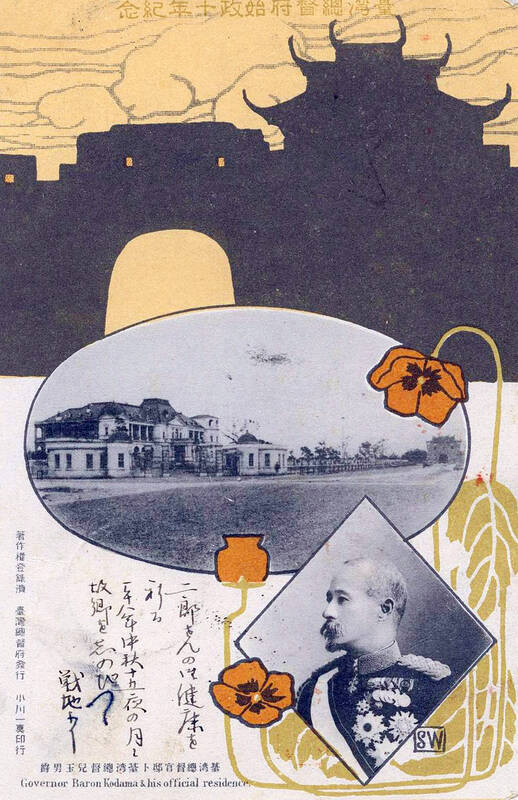

Members of the Japanese Diet were appalled at the ever-increasing costs to build Governor-General Gentaro Kodama’s residence in Taipei. Not only did the colonial government keep adding items to the grand complex, they also tapped into funds allocated for the Taiwan Shinto Shrine. That was blasphemy!

“I can’t imagine how much they would have spent to build what kind of palace if Shimpei Goto had his way,” civil engineer Hampei Nagao recalls in Story of the Governor-General’s Office (總督府物語), a book by Huang Chun-ming (黃俊銘).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Goto, the civil administrator of Taiwan, was summoned to Japan to explain. He asserted that the residence represented the emperor’s authority in the nation’s southward expansion, and of course it had to be as stately and beautiful as possible. How else would the Taiwanese, most of whom had never been to Japan, fully understand the power and prosperity of the motherland?

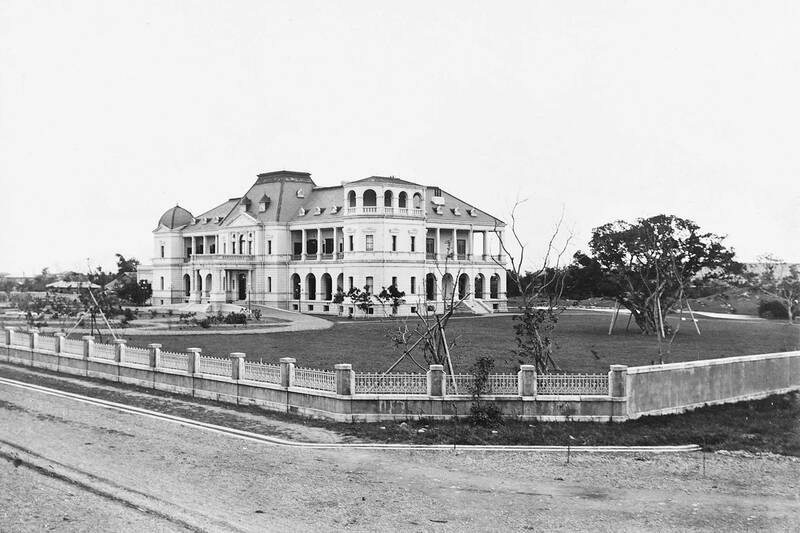

The Renaissance-style mansion surrounded by a Japanese garden and wide boulevards was completed on Sept. 26, 1901. The governor-general not only lived in this complex, he also received guests, hosted banquets and hosted all sorts of celebrations and public events. It also served as his office until 1920, when the structure that houses today’s Presidential Office was completed.

The residence was built in conjunction with the Taiwan Shinto Shrine as the two main symbols of colonial might. All visiting royals stayed in the residence, and a wide, tree-lined road was built between the two sites, leading to the demolition of Taipei’s Qing Dynasty-era city walls.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

To further accommodate the royals, the building was expanded and given a makeover in 1911, and this version still stands today as the Taipei Guest House on Ketagalan Blvd and Zhongshan South Road.

PREVIOUS RESIDENCES

The Japanese took Taipei with little resistance on June 14, 1895. The Governor General’s Office was temporarily set up in the Qing Dynasty’s Provincial Administration Hall, located next to today’s Zhongshan Hall.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

The first governor-general, Sukenori Kabayama, also moved into the complex. The Japanese were not used to this traditional Chinese structure and tried to remake it to suit their habits; but ultimately, a Chinese building could never represent Japanese authority.

Kabayama only lived here for two months before he moved into the Western Learning Hall (西學堂), which was established in 1887 by Qing provincial governor Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳) to train officials to handle the increasing presence of Westerners in Taiwan. The school shut down in 1891 due to budget issues.

Like many structures of its time, the East-West hybrid complex consisted of three one-story brick structures with European arched verandas that formed a courtyard, but with Taiwanese-style red tile roofs. However, in December 1896, the third governor-general Maresuke Nogi built a Japanese-style house with tatamis next to the complex and lived there instead. The complex was later designated a historic site called the Nogi Hall, but it was demolished after World War II.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In August 1900, with the help of British engineer W. K. Burton (who designed Japan’s first skyscrapers), the government finalized an extensive urban planning project for Taipei, which included the governor-general’s residence and the Taipei Shinto Shrine. Civil engineer Yoshitaro Togawa says in Huang’s book that they were instructed to make them as stately as possible, and they were even ordered to begin construction and complete them around the same time.

MULTIFUNCTIONAL COMPLEX

Gentaro Kodama, the fourth governor-general, placed much importance on these two projects, and often rode his horse between the two sites to inspect construction progress. The shrine was dedicated to Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa, who died while fighting the local resistance in the south in 1895. It needed to be completed before the sixth anniversary of his death on Oct. 27, 1901.

The residence was finished on Sept. 26, 1901, and the prince’s widow became the first royal to stay there when she arrived the following month to inaugurate the shrine.

“If the governor-general’s residence was the highest ruling authority in Taiwan, then the Taiwan Shinto Shrine symbolized the ruler of the motherland, the emperor,” Huang writes. “The urban planning around these two structures also demonstrated the close relationship between politics and religion.”

Designed by Togo Fukuda, the brick and stone Renaissance-style structure was surrounded on all sides with verandas. Unlike typical Japanese mansions, only the east wing of the second floor was completely private to the governor-general and his family.

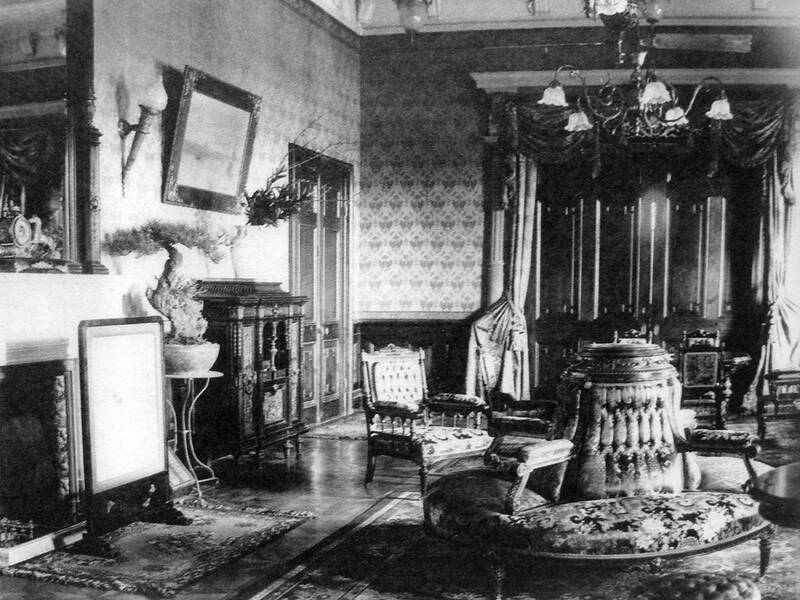

The first floor contained the reception lobby, administrative offices, meeting rooms, a spacious banquet hall and a game room featuring billiards and other high-society entertainment.

During those days, if an important visitor brought a female companion, the governor-general and his wife would greet them first, then they would separate by gender into different rooms to socialize. This “female meeting room” was located on the second floor of the west wing, where the guest rooms, a small dining hall and servant quarters were also located. In the center of the second floor was a room displaying rare collectibles.

The trees in the garden were transplanted from Beitou District, and Kodama had two giant banyan trees moved here from today’s Guting area. To save money, they enlisted prisoners to help move the trees, and when power lines got in the way, Kodama asked the Department of Communications to temporarily sever them.

ROYAL ENJOYMENT

At first, the residence was not designed to accommodate royals, who usually traveled with dozens of people to serve their needs. By 1911, the wooden framing was also damaged by termites, so the government launched an expansion and renovation project.

The building took on more splendorous Baroque features, as designers added new columns, a Mansard roof, chandeliers and replaced the curtains, carpets and furniture. New lighting and heating systems were installed, as well as a tennis court.

Government affairs shifted to the governor-general’s office after 1920, and the residence was used mainly for cultural and social events. In October 1916, for example, 46 Shinto, Buddhist, Taoist and Christian leaders attended a religious discussion with the governor-general, and in October 1921, intellectuals and social elites enjoyed a poetry gathering where they wrote calligraphy and composed pieces on the spot.

Subsequent governor-generals held meet-and-greets in the garden, and Eizo Ishizuka’s reception in 1929 reportedly attracted more than 600 officials and civilians. Celebrations observing events such as the enthronement of the Showa Emperor, or the 30th anniversary of Japanese rule, were also held here.

The royals were the only guests allowed to stay at the residence. Crown Prince Hirohito fully enjoyed the facilities during his stay in 1923. After meeting with important locals on his first day, he played tennis, dined with Japanese officials in the banquet room, played billiards and then watched the welcoming lantern parade with 25,000 participants from the third-floor balcony. After Hirohito toured the colony and returned to Taipei, officials put on a massive Western-style banquet, with fireworks closing out the night.

After World War II, the provincial governor stayed in the residence until it was converted into the Taipei Guest House in 1950. The 1952 Treaty of Taipei, a peace agreement between Taiwan and Japan, was signed at the residence, and it continues to host similar functions as it did during the Japanese years.

Today, the residence opens once or twice per month to the public. Visit: subsite.mofa.gov.tw/entgh.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual