Unlike many of his relatives, Wu Sheng (吳晟) turned down several chances to emigrate to the US. The acclaimed poet and environmentalist, who turns 78 today, still lives in his hometown in rural Changhua County, where he farms, plants trees and writes about his love for the land.

His 1978 poem, American Citizen (美國籍), chides his elder brother, who left their “backward hometown” a decade earlier: “You’re ashamed of us / Like this small plot of land / This stupid plot of land / Which provides you no sense of pride or glory / Because we are unwilling to study / Those proud ABCs / We’re only willing to work, struggle and sweat in silence in our homeland.”

“I feel like I’m a regionalist, I just want to give my all to helping this land,” he tells the Taipei Times. “Some have criticized me for being narrow-minded, but I’m not saying that people shouldn’t go overseas. I just think that it’s very hollow for those who live here to keep looking outwards instead of caring for this place.”

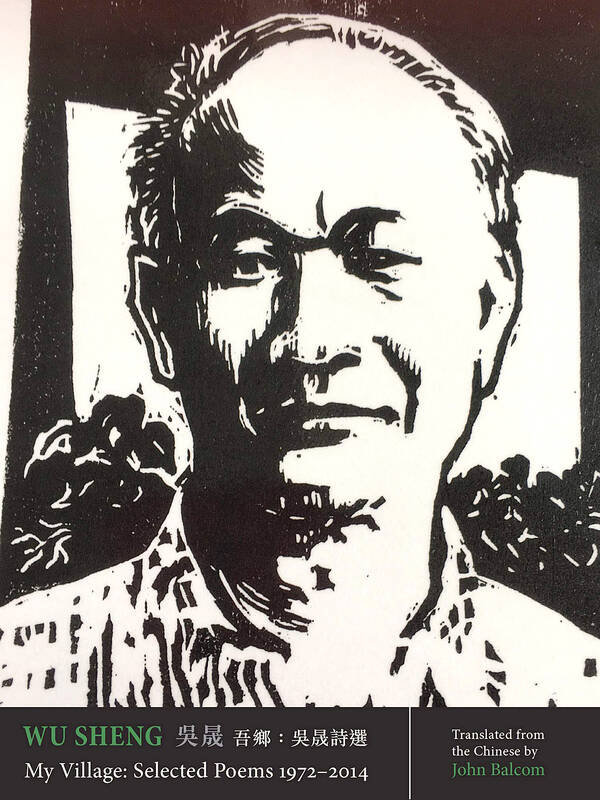

Photo courtesy of Fisfisa Media

Wu’s no-frills, heartfelt writing has become much more accessible to English readers in recent years with the 2020 release of My Village: Selected Poems 1972-2014 (吾鄉: 吳晟詩選), translated by John Balcom, and documentary He Is Still Young (他還年輕), which opened in theaters last Friday.

His deep devotion to the environment, expressed with urgency through his poetry and other endeavors, carries the 140-minute film, which is surprisingly watchable despite its length and lack of a plot. Viewers get an up-close look at Wu’s life in Changhua and the efforts he’s made to save and record Taiwan’s remaining beauty, particularly through the “Notes on Jhuoshuei River” (筆記濁水溪) series that he began two decades ago.

“Taiwan was a ‘treasure island’ that would still be a paradise if we had cherished it,” Wu says. “I lived through a time when our environment was still pristine. A lot of people today don’t feel it because they’ve only seen Taiwan as it is today. When I was young, the rivers were still full of fish and shrimp. Today, many rivers are dead. How can I not grieve?”

KEEPING IT REAL

I meet Wu at a cafe in Taipei’s Zhongshan Hall for what’s meant to be a 30 to 45 minute interview. I’m admittedly not much of a poetry connoisseur, but as Balcom writes in the book’s introduction, Wu’s work is “far different from the dense, nearly incomprehensible aesthetic objects produced by Taiwan’s fashionable modernist writers. Wu’s poems were neither abstract nor difficult: no dazzling imagery, no urbanity, no affected existential angst.”

At first glance, they even seem overly simplistic. But the vivid, personal tone and emotional weight packs a punch that quickly drew me in.

Photo courtesy of Fisfisa Media

We didn’t talk much about abstract topics anyway. As he expresses in I Won’t Discuss It With You” (我不和你談論): I won’t discuss life with you / I won’t discuss profound and mysterious thoughts with you / Let’s leave the study / Let me take you for a walk in the broad fields / To touch the cool, clear river water / And see how it silently irrigates the paddy fields.

His warm and sincere demeanor matches the style of his poems, and we end up casually chatting for well over an hour about his life and the topics he cares about.

“I write about the reality of our society, not the secrets in my heart. That’s why I write in a more narrative tone.”

Photo courtesy of Fisfisa Media

Wu says that he backs up his words with action. He was quite the political and environmental activist during the 80s and 90s, opposing various environmental projects. In 2010, he was a leading figure in the resistance that successfully halted the Kuokuang petrochemical complex planned on the wetlands at the mouth of his beloved Jhuoshui River (濁水溪), which was already damaged by other projects.

As he writes in My Mind FIlled With Worries (我心憂懷): Held hostage by a torrent called development that continues to spread far and wide / Pillaging the mountain forests, plundering the rivers / Pillaging the fields, plundering the coast / One piece of land after another, mortgaged off / Occupied, degraded, and later / Totally ruined, never to be restored.

RURAL ISSUES

Photo courtesy of Fisfisa Media

Although Wu extols rural life — “Looking after the island’s granary is the greatest honor,” he writes in the 2014 piece Come Back Together (一起回來呀) — he understands that contemporary life has made it impossible for most people to live that way.

Wu and his wife were both teachers, returning home after work to help his mother farm. He says he’s fortunate, as his siblings were willing to give or sell him their shares of the family property. Many family lands, which were already small due to the government’s land reform policies in the 1950s, became fractured through inheritance issues, eventually abandoned or sold off.

He dedicates much time to Pure Garden (純園), a two-hectare forest named after his late mother that he planted with mostly native species. The venture is for environmental and public recreational purposes, but people often ask him when the trees can be sold.

“I tell them, maybe in 100 years,” he quips.

The conversation eventually returns to Wu’s decision to not remain in the US after finishing the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1980s, and he and his wife were approved for the immigration process amid the 1995-1996 Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.

“Taiwan is all we have now,” he says.

Wu says brain drain from rural flight will only cause the countryside to further deteriorate.

“Why is local corruption so bad in the countryside? It’s because the intellectuals all left,” he says. “Every locale needs a few people with ability and ideals to fight for the place’s betterment. I don’t want to brag, but I don’t want to be too humble either. If we didn’t stand out back then, the Kuokuang plant would surely be completed.”

In You Too Have Left (你也走了), he writes: “You quietly left / The bitter land that bore you, raised you, taught you / The land that desperately needs the you who has grown up / To fight for her.”

Wu proposes that Taiwan Sugar Corp designate the tens of thousands acres of land it owns as a “food security reserve,” and recruit young potential farmers to practice and test their new ideas. After their abilities mature, they can rent other land to expand.

“Food security is homeland security, and it’s very important,” he says. “We also need to raise the social status of farmers. The image of the new farmer will be intellectuals with rural ideals.”

And, despite his old age, he vows to continue to promote these ideals.

“I feel like I still have some good ideas to offer, and that’s why I want to maintain a young mindset,” he says. “I need to write them down in my poetry, and then take action, as I always have done.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,