Sept. 5 to Sept. 11

Liu Hsi-yang (劉喜陽) was fired from his job at Niitaka Bank for starring in the first feature film set in Taiwan, Eye of the Buddha. It was considered inappropriate back then for him to moonlight as an entertainer, which was considered a lower class profession.

However, Liu caught the movie bug. A year after the film premiered in April 1924, he co-formed the Taiwan Film Research Association (臺灣映畫研究會) to further his interests and actualize his script titled Whose Fault Is It? (誰之過).

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

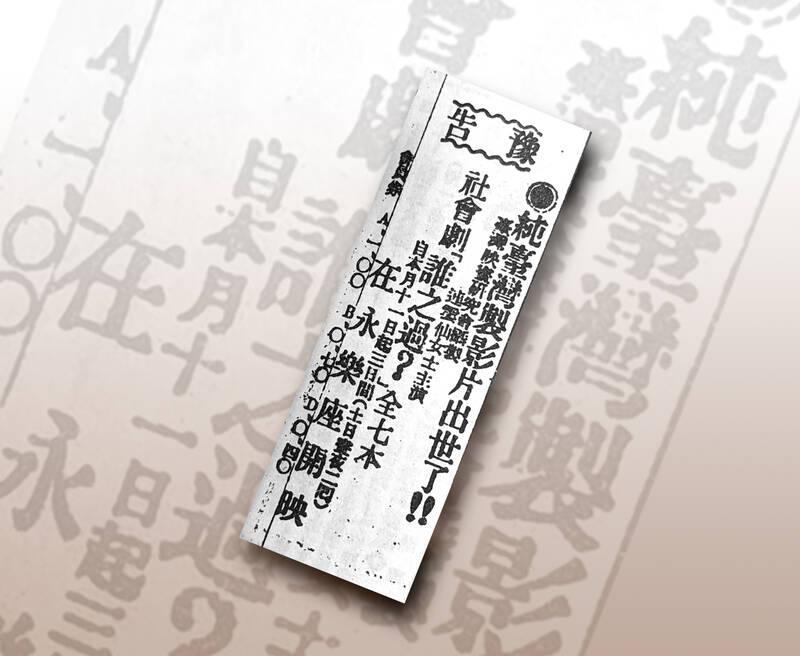

Liu’s dream came true on Sept. 11, 1925, when the association ran a tiny ad in the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) announcing, “The first purely Taiwanese-produced movie has been born!!”

Whose Fault Is It? ran for three days at the spacious Eirakuza (永樂座) theater in Taipei’s Dadaocheng area.

Shot in Beitou, Yuanshan and the New Park (today’s 228 Memorial Park), it told the story of spoiled, good-for-nothing playboy Lee Shih-chih (李勢至), who tries all sorts of underhanded tactics to marry Lin Pei-lan (林珮蘭), a modern lady who champions women’s issues. But Pei-lan is in love with coal mining technician Liu Ke-shan (劉克善), who later saves the day when Lee’s schemes go awry.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

It was a box office flop, and the association disbanded shortly afterward. The only trace of the movie’s existence is the ad and a short article introducing the film. Fortunately for historians, the article provides a complete synopsis of the plot that contains major spoilers, including the ending.

Local enthusiasts continued to try their hand at filmmaking over the years, but according to late historian Chuang Yung-ming (莊永明), the first commercially succesful venture wouldn’t come until 1938 with Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風), which also premiered at Eirakuza.

FIRST FEATURES

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

Chuang writes that the colonial government began developing a local film industry around 1921 to promote Japanese values and culture.

Prior to this, the Japanese had produced several documentaries on Taiwan to showcase the colony to the motherland and foreigners, most notably a 1907 series that covered the entire island.

Eye of the Buddha was the first attempt at a feature film, which commenced shooting in 1922. Directed by Kaneyuki Tanaka, the story was set in Dadaocheng, and although the main actors were Japanese, it featured a significant Taiwanese supporting cast.

Again, the movie synopsis in the local paper revealed the entire plot, which would be a huge no-no nowadays. The article on Eye of the Buddha was so detailed that it was split into two parts and run on consecutive days. In short, rich and powerful official tries to force a beautiful young woman into marriage, genius sculptor comes to her rescue and the official eventually repents in front of a huge Buddha statue and commits suicide. It’s not hard to see where Liu drew his inspiration for Whose Fault Is It?

The next Taiwan-set film, The Heavens are Cruel (老天無情), premiered in the four-story, 1500-seat Eirakuza theater, which opened its doors in February 1924 on today’s Dihua Street to great fanfare. The best-known of its co-owners was the tea tycoon Chen Tian-lai (陳天來).

Taiwanese intellectuals living under Japanese rule often looked towards China as the motherland, and the theater invited a Peking Opera troupe from Shanghai to perform on its opening day.

The space mostly showcased traditional Taiwanese and Chinese performances and plays, only screening the occasional movie. It also had a Western-style house band.

Eirakuza was also a popular spot for Taiwanese political activists to make speeches and hold rallies, and democracy pioneer Chiang Wei-shui’s (蔣渭水) funeral was held here.

Hitting the big screen in September 1924, The Heavens are Cruel was financed by the Taiwan Daily News. It was a mostly Japanese production featuring just one Taiwanese actor, but one of the producers was Lee Shu (李書), who would serve as cinematographer for Whose Fault Is it?

BOX OFFICE FLOP

The Taiwan Film Research Association boasted about 30 founding members, including a few Japanese and two women, and tea magnate Lee Chun-sheng’s (李春生) grandson Lee Yan-shu (李延旭) was elected chairman on the first meeting. Ironically, Lee Yan-shu’s elder brother Lee Yan-shi (李延禧) was the director of the Niitaka Bank that had fired Liu for acting.

The group met regularly at Lee Yan-shu’s office, focusing on bringing to life Liu’s script for Whose Fault Is It? They studied films imported from China, and Lee Shu even traveled to Shanghai to hone his film-developing skills. Liu and several members took the directors’ seat.

“The men and women of the Taiwan Film Research Association have been enthusiastically researching [the art of filmmaking] … and our actors’ expressions have become quite natural,” the Taiwan Daily News article states. “We are pleased with the results of our on-site shooting, and the film’s lighting is bright.”

It particularly mentions lead actress Lien Yun-hsien (連雲仙): “She’s nimble and graceful, and has a rich range of facial expressions. Her every movement is convincingly real, and her skills are comparable to actresses in China. In fact, she may be even better.”

It’s not clear what happened to Liu after the disappointing reception of Whose Fault Is it?, and there would only be three more Taiwanese-produced films for the rest of the Japanese era, according to a National Taiwan Library document. This was also Lien’s only film credit.

Eirakuza continued to run as a multi-purpose performance space after World War II, particularly for Peking Opera.

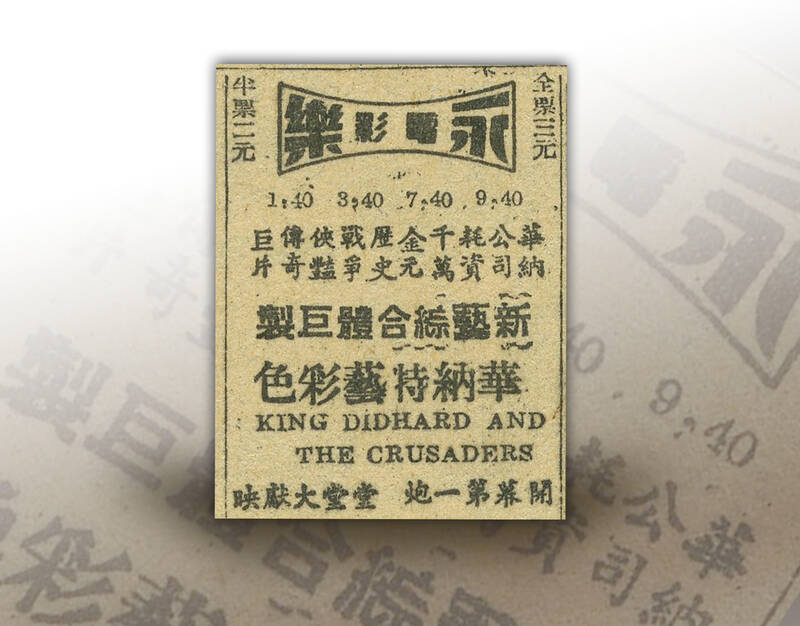

In 1954, it started regularly screening movies, first showing the Hollywood blockbuster King Richard and the Crusaders, which was also a critical disappointment.

However, the old theater could no longer keep up with the state-of-the-art movie houses that sprung up in Taipei over the years, and it shuttered its doors in May 1960.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that