Aug 15 to Aug 21

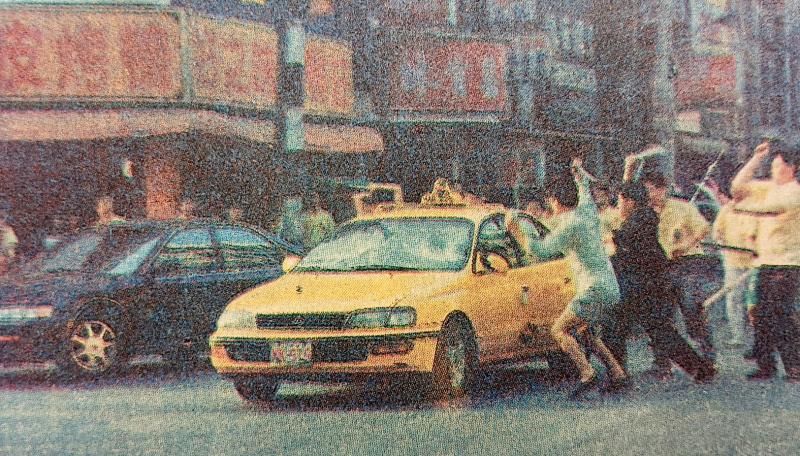

Within hours, a minor traffic dispute between two taxi drivers had escalated into a full-out street brawl involving hundreds of combatants.

Armed with metal bats, car locks and even tear gas, the midnight battle on Aug. 17, 1995 between Chuan Ming (全民) and Beiqu (北區) taxi drivers associations lasted for over four hours at the roundabout on Tingzhou Road (汀州路) in Taipei. Scattered clashes also broke out in other areas of the capital, as well as in what is today’s New Taipei City.

Photo: Chuang Yu-kuan, Taipei Times

The crowd dispersed around 4:30am, but peace lasted only a few hours. Around 7am, about 50 Beiqu cars, each carrying five armed men, stormed Chuan Ming’s headquarters in Sanchong District (三重). They smashed up more than 20 vehicles and blew up one of the shipping container offices with petrol bombs.

Then-Taipei County Commissioner Yu Ching (尤清) managed to broker a truce that evening, but just minutes later, the discovery of five Beiqu drivers who were seriously injured by samurai swords rekindled the violence.

The fighting went on until Yu finally convinced the two sides to apologize to the public on Aug 19. It was a huge blow for the already poor image of the nation’s taxis, especially since the government had just approved a fare hike and requested them to improve their service. The police were panned for their inability to contain the situation, leading to calls for reform. And it was surely not a good look for Taiwan, as the world was watching it due to the unfolding Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.

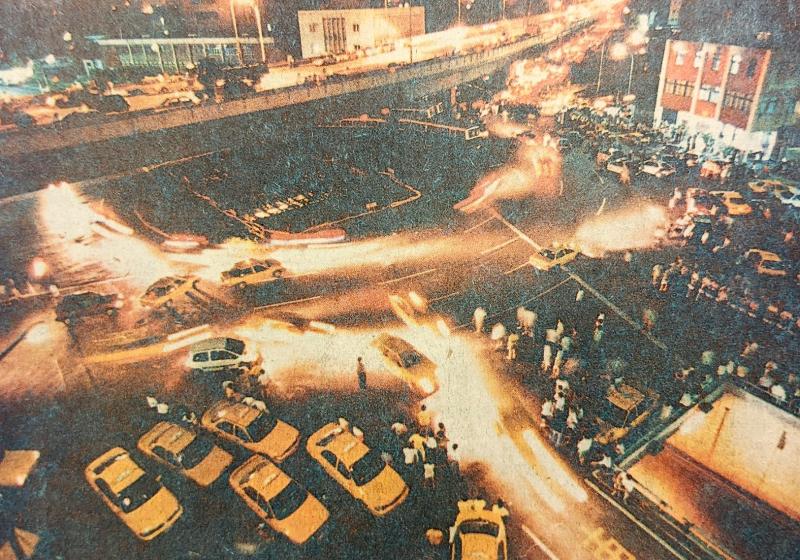

Photo: Hsu Hsiu-min, Taipei Times

DRIVERS UNITE

Shen Chia-hsin (沈嘉信) writes in the 1997 study, “The development of social activist groups: Chuan Ming Taxi Association’s violent behavior and image as an example” (社會運動團體的發展:以全民計程車司機聯誼會暴力行為與形象為例) that such associations developed initially to combat the government’s restrictions on issuing taxi licenses. Due to the difficulty in obtaining a license on their own, drivers were often heavily exploited by cab companies.

When the government again suspended the issuing of new licenses in 1986, the drivers banded together and called for the right to operate independently. Chuan Ming was founded in 1993, its members brought together by an underground radio station of the same name that ran a weekly show where they could call in and discuss their problems. Within a month of its establishment, it was able to rally nearly 300 cars to protest in front of the Ministry of Transportation. By early 1994, Chuan Ming had established its headquarters under the Chongsin Bridge (重新橋) in Sanchong, and hundreds of drivers could be seen hanging out there.

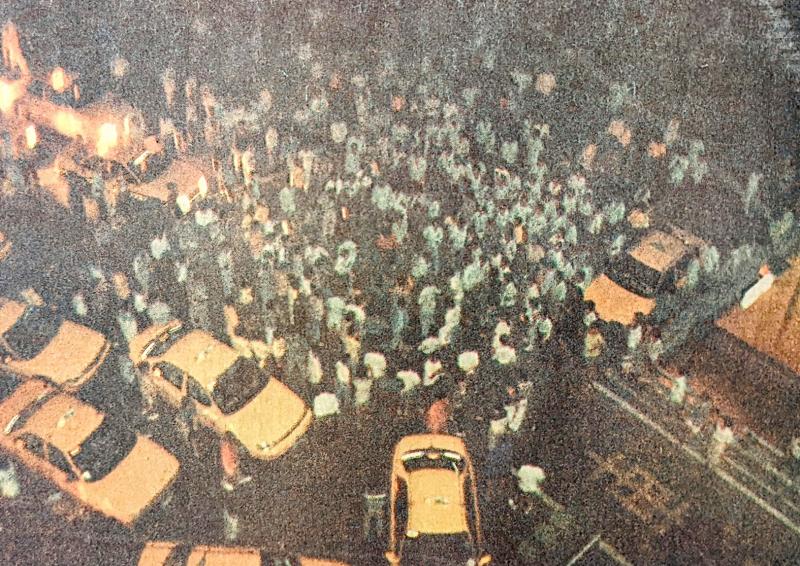

Photo: Hsu Hsiu-min, Taipei Times

Having not received a satisfactory government response, Chuan Ming started participating in various major demonstrations and became ardent supporters of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). They were a formidable force during protests, and also provided services like giving elderly people rides during a march. They eventually became known for their penchant for violence, however, most notably attacking the police with petrol bombs in July 1994 to stop them from shutting down the underground radio station Voice of Taiwan (台灣之聲).

After mishearing that New Party (新黨) provincial governor candidate Chu Kao-cheng (朱高正) beat up his DPP opponent Chen Ting-nan (陳定南) that November, Chuan Ming drivers surrounded Chu’s headquarters in Taichung, knocked down their flags and almost came to blows with the staffers before DPP politicians rushed to the scene to stop them.

In December 1994, Chuan Ming drivers were involved in a brawl over a parking dispute with a New Party-supporting Mainlander gang, and a driver was stabbed to death during the chaos. Ridership fell after this incident, and many drivers had to hide their membership to survive, keeping a low profile until things exploded in August 1995 against the newly formed Beiqu association.

FIGHTING IN THE STREETS

It was not the first time taxi drivers fought each other in Taipei. The Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) reported traffic disputes turning violent in January 1992 and March 1993, each time involving dozens of cabs.

But the fighting on Aug 17, 1995 was unprecedented. Beiqu was barely a month old at that time. And although during their founding ceremony they firmly denied that their goal was to compete with Chuan Ming, the media voiced their doubts.

Yu was broadcasting the truce to the public through the radio around 8pm that night when Beiqu association leaders learned of the brutal attack on its drivers. They yelled for Yu to stop, declaring, “That agreement no longer counts! We will fight to the end!”

An hour later, they attacked Chuan Ming headquarters again, while Chuan Ming responded by hurling a torrent of petrol bombs and smashing up the Beiqu cars after the drivers fled. It was utter chaos in the dark; fires were erupting everywhere and drivers were jumping into their damaged vehicles and ramming their opponents. Things didn’t calm down until around 1am, with an estimated 50 people injured and over 100 vehicles destroyed. The two sides had no intention to stop, as they rallied members from across the nation to head toward Taipei.

The phones in the National Police Agency rang nonstop the following day with affected residents slamming the officers for their inability to control the situation. The police finally raided the headquarters of the four taxi fleets involved that day, confiscating hundreds of homemade fire bombs and sharpened metal sticks. Chuan Ming members sat on the road in protest afterward, arguing that they only amassed so many weapons to protect themselves due to police incompetence. They only dispersed after the police promised that they would protect them from any further attacks. Both associations later apologized to the public at a second meeting called by Yu, and vowed to put an end to the violence.

Footage of the chaos made the international media, and tourism operators worried that it would scare tourists away. The nation was already in a precarious situation as the Third Taiwan Strait crisis was unfolding, and political commentators were concerned that the situation would hurt Taiwan’s image as a peaceful and democratic nation worth international support.

The taxi industry also suffered as ridership dropped immediately, with many residents telling the media that they would rather take the bus. The Taipei City Government postponed the fare hike, and it took a while for things to recover.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of