Chris Findler says that the introduction of neural machine translation software has reduced the demand for human translators.

“I am pessimistic about the future of traditional translation jobs,” says Findler, a lecturer of translation and interpretation at National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU).

Online translators such as DeepL Translator, Yandex and Babylon offer accurate translations in dozens of languages, which means that a human translator may no longer be necessary for some jobs.

Photo: Wesley Lewis

Machine translation software’s growing influence is irreversible. Translation software can utilize artificial neural networks and large databases in order to accurately predict sequences of words and provide nuanced expressions in their results. AI’s presence in the field cannot be ignored, and translators in a variety of specialties will need to adapt to new job descriptions.

“With artificial intelligence taking over, some translation jobs will be more like editor jobs” Findler says.

Translation AI could be seen as a threat to jobs, but it has also created a new post-machine editing role. Findler says that there is a large demand for translators to edit and add a “human touch” to texts that have already been machine translated.

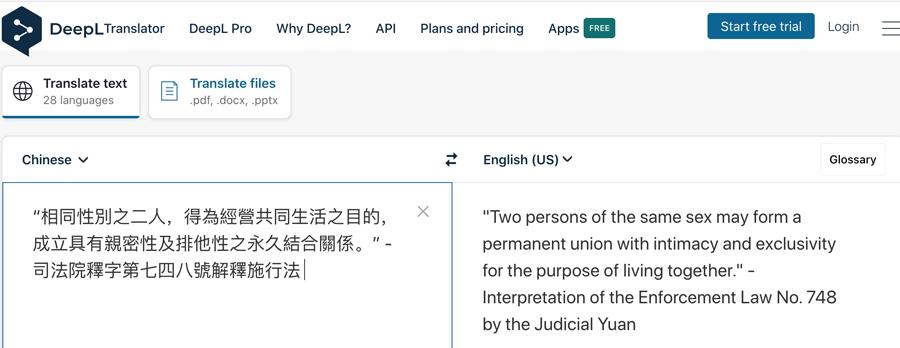

Photo: Wesley Lewis

Interpreters, and those in technical or media translation are more likely to be threatened or impacted by AI. Findler says that interpreters may eventually disappear due to AI’s ability to recognize speech and instantly process it to text. He adds that museum and literary translation are less threatened.

In Findler’s experience, museums in Taiwan still want to hire translators, but businesses are keener to opt for the more cost-effective option of using an online translation service. Furthermore, technical translators tend to deal with texts with repetitive language, which can more easily be machine translated.

Perry Svensson, the former head of translation at Taipei Times, says approximately 40 to 50 percent of his freelance Chinese-to-English and English-to-Swedish work is post-machine editing. He fixes the errors the machine translator might have made.

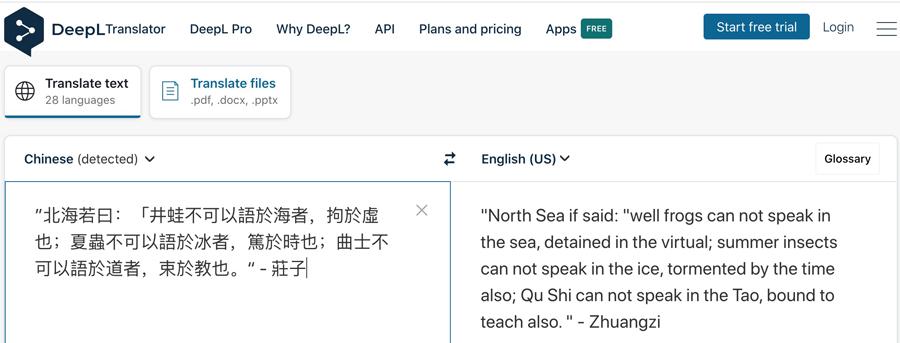

Photo: Wesley Lewis

He adds that most of his translation jobs five years ago were not already machine translated and required him to translate from scratch.

Svensson often uses DeepL Translator for articles and he makes minor changes to the translated text afterwards. Machine translators prove to be helpful when he is faced with multiple projects and deadlines.

Although they are useful, free machine translation services have decreased the amount of freelance translation jobs. Svensson translates for newspapers, logistics companies, as well as business ethics codes and product manuals. His advice for translators is to have multiple specialties in case AI renders human translators obsolete in a specific field.

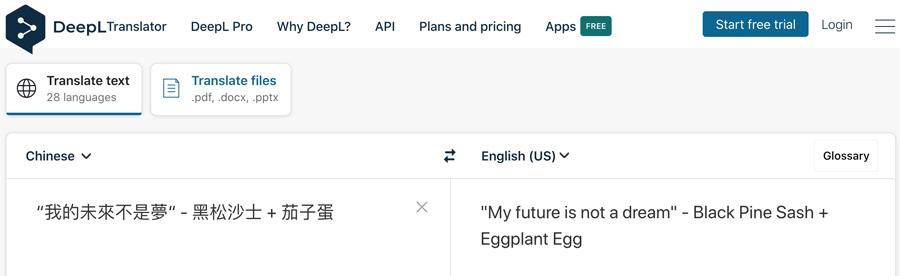

Photo: Wesley Lewis

“If you are into photography, then your knowledge of that field will make for better translations,” Svensson says.

Ines Tsai (蔡淑瑛) works in television and translates for tourism programs, among others. She says that the technology for auto-generated subtitles exists, but it has not yet replaced human translators.

In her work she also comes across jobs where she is tasked to edit machine translated subtitles. She says that much of her work is to capture colloquial speech, jokes, idioms and other aspects of language that are still difficult for a machine to register and translate correctly.

For the moment, literary translators remain the least affected by machine translation software.

“Literary translation is a creative task that requires deep knowledge about multiple languages, cultures and literary traditions,” says Ji Lianbi (計連碧), a literary translation graduate student at Boston University.

Ji says that software can understand the basic meaning of a sentence but a word-for-word translation is often inauthentic and less expressive in the target language.

Anna Zelinska-Elliot, the director of literary translation at Boston University, says universities should be obligated to prepare translation students for a more technology-oriented profession. She adds that non-literary translation classes should address the impacts that machine translation is having in their field.

Although literary translation is not as impacted by AI, Zelinska-Elliot says that universities should familiarize the students with various online dictionaries, but not necessarily online translators.

As a university lecturer, Findler is afraid that students will be discouraged to study translation due to improving AI. He thinks that universities should merge interpretation and translation programs to produce well-rounded students as well as inform the students of the evolving job market.

Although AI has yet to completely replace human translators, there is no way to avoid its encroachment on their jobs.

For Findler, the future of the translation field is set in stone, adding that many traditional translation jobs, “are going to go the way of the horse and buggy.”

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the