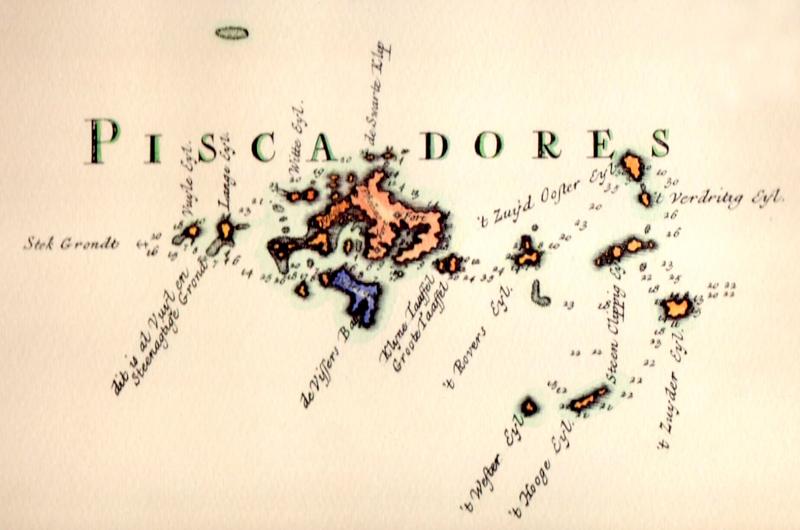

Aug. 1 to Aug. 7

Admiral Cornelius Reijersen stubbornly held out at Penghu’s Makung harbor (馬公) for nearly two years, refusing the Ming Dynasty’s repeated requests for his fleet to depart for Taiwan.

Instead, the Dutch fleet plundered Chinese merchant ships, captured sailors and terrorized the coast of Fujian for months, hoping to force the Ming to open up trade with them.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

To the Ming, Penghu was too close to home; they knew of the Dutch’s military strength and they were also worried that the archipelago would become a pirate haven with ships smuggling goods there to avoid paying taxes. They did not consider Taiwan to be under their jurisdiction, and had no problem with them relocating there.

But Reijersen had already surveyed the west coast of Taiwan when they first arrived in July 1622, and could not find a harbor deep enough for the fleet to dock.

More than a year of negotiations and clashes later, the Ming had had enough. In August 1624, a fleet of 200 ships and 10,000 troops surrounded Makung and cut off its supply routes. They didn’t even want the Dutch in Taiwan anymore and they wanted to force them back to their headquarters in Batavia (present day Jakarta).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At this time, the influential smuggler Li Dan (李旦), known to Europeans as “Captain China,” stepped in and brokered a truce between the two sides. The Dutch finally packed up and set sail for Taiovan (today’s Tainan area), and the rest is history.

FIRST OCCUPATION

Dutch interest in Asia began in 1602 with the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). They immediately clashed with the Portuguese, who had been active in the area for nearly a century. In 1603, the Dutch captured the Portuguese merchant ship Santa Catarina in the Malacca Strait, which was loaded with Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain. They made a fortune auctioning off the items in Europe, and this event sparked their determination to open up trade with the Ming Dynasty.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1604, vice admiral Wybrand van Warwijck set sail for Macau in an attempt to drive out the Portuguese. However, a typhoon forced his fleet to take shelter in Penghu, where he began building a permanent base. He then contacted the Ming authorities in Fujian with the hope of negotiating trade privileges, but the powerful eunuch Kao Tsai (高寀) told him he had to pay an exorbitant fee to reach the emperor.

Many sources state that van Warwijck rejected the offer, but Yang Tu (楊渡) writes in the new book, Dutch Ships in Penghu Bay (澎湖灣的荷蘭船) that he paid part of it and began privately trading with Fujian merchants while he waited for news from Kao.

Meanwhile, the Ming officials in Fujian were eager to get rid of the Dutch. After much debate, General Shen Yourong (沈有容) set out for Penghu with 50 warships and 3,000 troops. He did not want conflict; he hoped that his vastly superior numbers were enough.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Shen was courteous and released the interpreter they captured earlier as a sign of goodwill. However, he stopped all ships from leaving the harbor and had troops patrol the coast. Shen was awed by the size of the Dutch warships and their mighty cannons, but he remained firm, as there were only three of them at Penghu.

Fortunately for van Warwijck, the man who was supposed to deliver the money to Kao had not left Penghu yet, and he got his cash back, Yang writes. However, he still refused to leave, and a month passed before the he and Shen met at Makung’s Tianhou Temple (天后宮). Shen told him that more troops were coming from Fujian, and gave him one last chance to leave peacefully. Van Warwijck obliged.

RAIDING DUTCHMEN

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

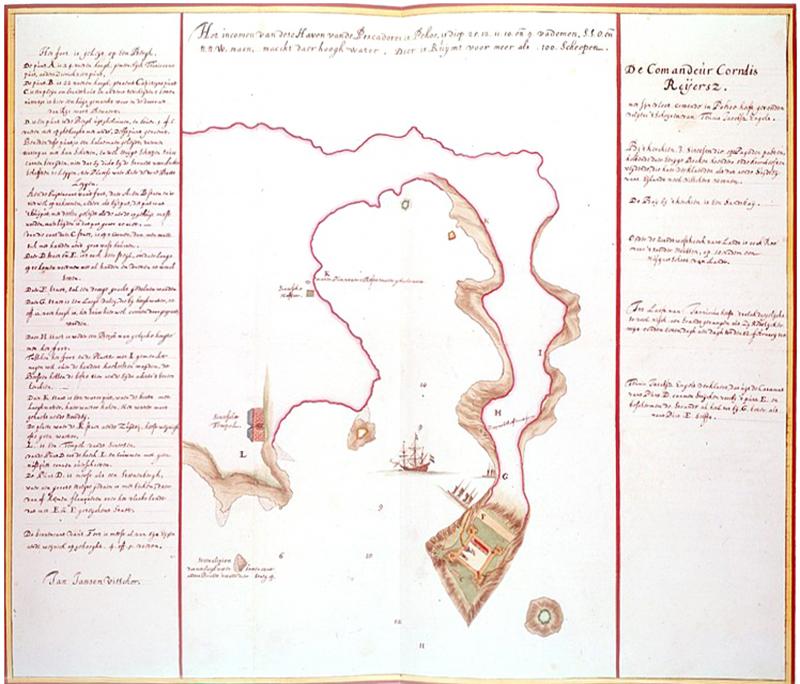

The Dutch continued to attempt to dislodge the Portuguese and get the Ming Dynasty to trade with them, to no avail. After launching an unsuccessful attack on Macau in 1622, admiral Cornelius Reijersen retreated to Penghu. They did consider Taiwan, but the Dutch traversed the west coast and could not find a harbor deep enough for their ships. They returned to Penghu and started building fortifications around Makung harbor in August 1622.

Alarmed, a Fujian official arrived and told Reijersen that the Ming were willing to trade with the Dutch, they just didn’t want them in Penghu. Reijersen writes in a letter to the VOC that the official promised to have a guide bring them to Tamsui in northern Taiwan, a place outside of Ming jurisdiction, where there was abundant gold and food, as well as a large harbor for their ships. They could freely trade with the Ming there.

This was too good to be true, and Reijersen insisted on staying in Penghu, threatening to capture any Chinese ship that passed through the nearby waters. They also raided the Chinese coast, attacking the port of Zhangzhou on Oct. 18, 1622, burning up to 80 boats and taking dozens of prisoners. They also plundered local villages, seizing livestock and supplies.

James Davidson writes in The Island of Formosa: Past and Present that these captured sailors and locals were forced to help build the forts. The conditions were so harsh that 1,300 of the 1,500 workers died, mostly from starvation. The Dutch argued that their people were treated just as badly by the Ming.

“Furthermore, batches of natives were sent to Batavia to be sold as slaves, and the awful fact is recorded that less than half of them reached their destination alive,” Davidson writes. “Several villages on the coast were ravaged, and many cruelties committed, actions which were characterized by [historian Valentyn] as a disgrace to Christianity.”

The actions of the Dutch caused all merchant ships to cease visiting Penghu, and they began running low on food and supplies as the land was poor and sparsely populated. The northerly winds started howling as winter fell, and the men were falling ill from disease. The Dutch continued their plundering to survive, but Reijersen knew this was not a long term solution. Meanwhile, he sent an expedition to Taiovan to build a fortress and trade with smugglers there.

TAIWAN BOUND

Fujian officials tried to keep the news under wrap, but the emperor finally learned of the Dutch aggression and immediately installed Nan Ju-yi (南居益) as the new governor in August 1823. Nan asked the Dutch to leave Penghu and Taiwan and release the captives, while Reijersen said he had no authority to leave and wanted the Ming to stop trading with the Spanish in Manila. With talks making little progress, the two sides prepared for war.

After a few months of clashes, the desperate Reijersen finally contacted Batavia for permission to leave, and tendered his resignation. Martinus Sonck arrived in Penghu to replace him on Aug. 1, 1624, by which time 150 warships carrying 4,000 Ming soldiers were readying an attack. This number continued to grow over the following weeks. Sonck was instructed to avoid fighting due to VOC’s financial difficulties, but the Ming were tired of negotiating.

At this time, the influential smuggler Lee stepped in. Lee persuaded the two sides to agree on the Dutch peacefully leaving Penghu and occupying Taiovan, where they could freely trade with the Ming. This changed Taiwan’s fate forever, with Sonck becoming its first Dutch governor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of