July 25 to July 31

The Chinese Civil War was not on Chang Hung-ming’s (張鴻明) mind when he arrived in Taiwan in the summer of 1948. The Quanzhou, Fujian native only left his hometown because the village’s Wangye (王爺) deity told him that to stay would bring disaster. Chang’s cousin had just been transferred by the Republic of China Air Force from Nanjing to Tainan, so Chang decided to visit him there.

Chang did not plan to stay long, and all he brought were some clothes and a bit of cash. He didn’t even tell his family he was leaving because he didn’t want them to worry and try to stop him.

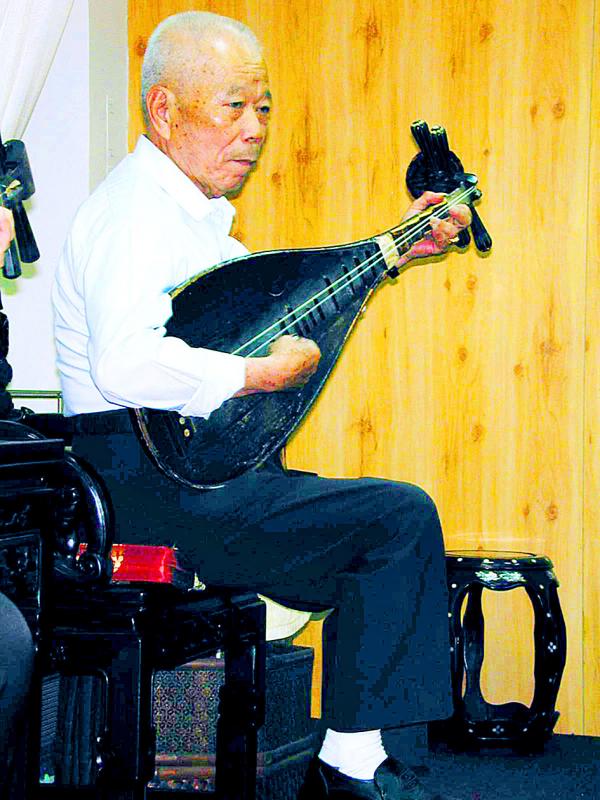

Photo courtesy of Nansheng She

As Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) officials, soldiers and refugees were migrating to Taiwan en masse, Chang decided to pack his bags in early 1949 and return home to his wife and newborn child. After several delays due to typhoons and unrest, martial law was declared in Fujian, cutting off all travel by boat. Quanzhou fell to the People’s Liberation Army in September 1949, stranding Chang in Taiwan for the next four decades with no means to contact his family.

Chang joined the Air Force, but his true passion was performing the traditional nanguan (南管) music that has its roots in Quanzhou. Luckily for him, Quanzhou was the ancestral home for the majority of Han Taiwanese, and there was an active nanguan scene in Tainan where he settled.

He became one of the most acclaimed performers and teachers in the nation, and led the Nansheng She ensemble (南聲社) on a tour of Europe in 1982. Chang was designated a “national treasure” in 2010 and was still accepting students when he died at the age of 93 on July 26, 2013. He was given a traditional nanguan-style funeral, which had rarely been seen in Taiwan.

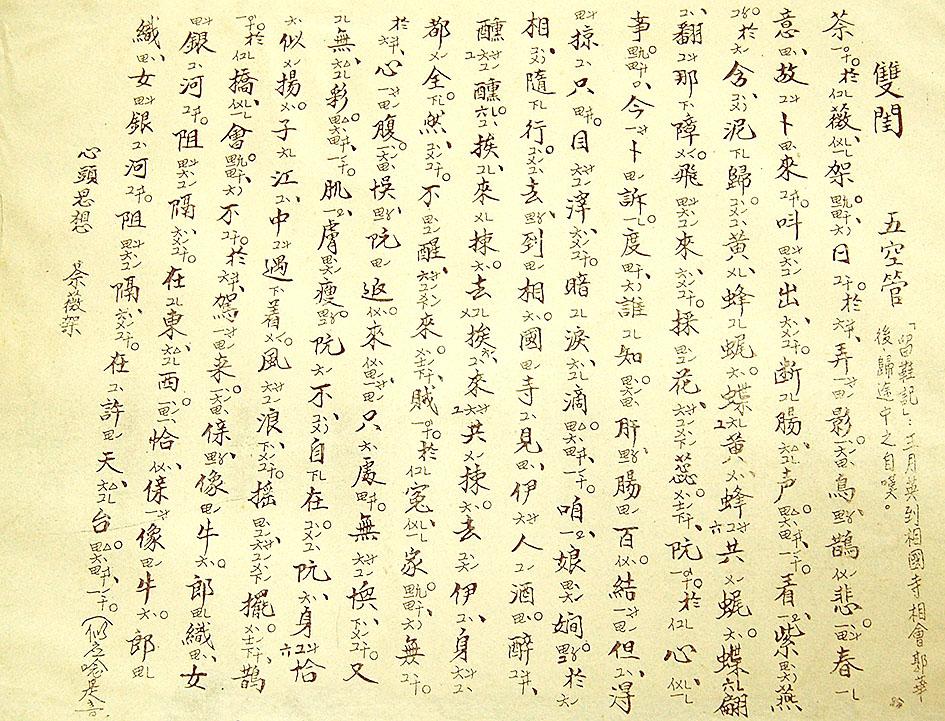

Photo: Hung Jui-chin, Taipei Times

NANGUAN VILLAGE

Chang was born Chang Shui-keng (張水坑) in 1920 to a farming and salt producing family in Dongyuan Village (東園村), Tongan County (同安), but the clan traces its ancestry to nearby Kinmen. According to his biography by Lu Chung-kuan (呂鍾寬), Chang’s commander in the Air Force changed his name to Hung-ming in 1954, because he thought that Shui-keng, which literally means “puddle,” was too crass.

Boasting 22 musicians, the village was known in southern Fujian for its nanguan performances, and Chang’s uncle, elder brother and cousin were all avid performers. It was the main form of entertainment for locals and was also heard at weddings, funerals, ceremonies and other events.

Photo: Hung Jui-chin, Taipei Times

When Chang was six years old, a clan member returned from Malaysia and the family put on a nanguan show for the occasion. Chang was mesmerized. He refused to go to bed, and after he was dragged to his room by his mother, he snuck out to keep listening.

He begged his father to teach him, and after much pestering, he was able to learn his first song: Going to Qin State (去秦邦). Chang later began training with a relative and also learned from his older brother Chang Tsai-wo (張在我). When he was 12, the clan invited renowned performer Kao Ming-wang (高銘網) to be the village teacher. Kao stayed at the family home and Chang served him as if he were his father. His skills improved rapidly.

When Chang’s father fell ill in 1948, he sought the advice of the local Wangye deity, who told him that while his father’s time had come, Chang was also in danger due to his unborn child. The only way to avoid misfortune was to leave. Chang thought of going to Southeast Asia, but he couldn’t locate any relatives, so he decided on Taiwan, eventually arriving in Tainan where his cousin lived.

Photo: Chang Tsun-wei, Taipei Times

Chang tried to return home several times, but his cousin told him to stay put as the Chinese Civil War had reached Fujian. He tried to leave again after his family sent him a letter regarding the birth of his daughter, but the journey was canceled due to a typhoon. That was his last chance.

LOCAL LEGEND

Since Chang spoke basic Mandarin, he spent his early days in the army as a translator. Chang’s comrades at the Air Force base were mostly from northern China, and for the first few years he heard little nanguan music. He knew it existed in Tainan, however, as he heard a rickshaw driver humming a nanguan tune.

Photo: Tsai Wen-chu, Taipei Times

After settling down, he began visiting the local barber, and noticed that he had a bamboo flute hanging on his wall. One time, Chang began whistling a nanguan song; the barber whistled back and the two became friends. After closing shop, the barber brought Chang to the Nansheng She ensemble, which had been active in Tainan since 1915.

Chang had little free time to leave the base and was under curfew, which hampered his participation since the ensemble usually practiced at night. He rose to a position that was free of such restrictions in 1954, and became a mainstay in the local nanguan scene. Locals called him “Air Force Chang.”

Although Nansheng She was growing, it was missing a lead pipa player. Chang’s appearance was a godsend, Lu writes, otherwise then-leader Wu Tao-hung (吳道宏) had to juggle two roles, often keeping him on stage for four hours without bathroom breaks. Chang became the group’s master teacher in 1971, and he later also taught at Taipei National University of the Arts.

Chang’s most accomplished student was Tsai Hsiao-yueh (蔡小月), who first learned under Wu at the age of 15. Tsai had two solo records by the time she was 21, and although she stopped performing after getting married, she traveled to France in 1982 and 1991 to record six albums with Radio France.

REUNITED

After more than two decades in the army, Chang was offered a promotion to sergeant, which required him to serve at least eight more years. The 51-year-old turned it down due to his desire to search for his wife and children. As a soldier, he was forbidden from leaving the country or sending letters abroad.

Nansheng She had much interaction with its counterparts in the Philippines between the 1960s and 1980s. Since many musicians there also came from the Quanzhou area, Chang diligently went on every trip to see if he could find any information about his family. He was finally able to meet his older brother, who was part of a Xiamen nanguan delegation, during an international event in Manila in 1980.

The brothers were overjoyed to see each other, but they had to suppress their emotions: “We were afraid that the reporters would see it … and there are also spies here,” he recalls. “When we met, we didn’t know what to say because I could not be seen interacting with people from the mainland.”

In 1989, after 40 years away, Chang was finally able to go home and see his wife, child and grandchildren. He went first to the Wangye temple to inform the deity how long his trip ended up taking.

Upon seeing him, his wife Lee Ching-pao (李清苞) reportedly lamented: “I’m 65 now, I’ve spent the last 40 years crying in a field.” In 2002, Lee moved to Taiwan where she remained until Chang’s death.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Nov. 11 to Nov. 17 People may call Taipei a “living hell for pedestrians,” but back in the 1960s and 1970s, citizens were even discouraged from crossing major roads on foot. And there weren’t crosswalks or pedestrian signals at busy intersections. A 1978 editorial in the China Times (中國時報) reflected the government’s car-centric attitude: “Pedestrians too often risk their lives to compete with vehicles over road use instead of using an overpass. If they get hit by a car, who can they blame?” Taipei’s car traffic was growing exponentially during the 1960s, and along with it the frequency of accidents. The policy

Hourglass-shaped sex toys casually glide along a conveyor belt through an airy new store in Tokyo, the latest attempt by Japanese manufacturer Tenga to sell adult products without the shame that is often attached. At first glance it’s not even obvious that the sleek, colorful products on display are Japan’s favorite sex toys for men, but the store has drawn a stream of couples and tourists since opening this year. “Its openness surprised me,” said customer Masafumi Kawasaki, 45, “and made me a bit embarrassed that I’d had a ‘naughty’ image” of the company. I might have thought this was some kind

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest

The room glows vibrant pink, the floor flooded with hundreds of tiny pink marbles. As I approach the two chairs and a plush baroque sofa of matching fuchsia, what at first appears to be a scene of domestic bliss reveals itself to be anything but as gnarled metal nails and sharp spikes protrude from the cushions. An eerie cutout of a woman recoils into the armrest. This mixed-media installation captures generations of female anguish in Yun Suknam’s native South Korea, reflecting her observations and lived experience of the subjugated and serviceable housewife. The marbles are the mother’s sweat and tears,