Bukin Syu has only been using his current name for two years, adopting it after he began studying the lost tongue of his Taivoan ancestors. The Taiovan are one of the Pingpu, or plains indigenous groups who are not recognized by the government, and they have been using Chinese names for so long that Bukin isn’t sure how their original naming system worked.

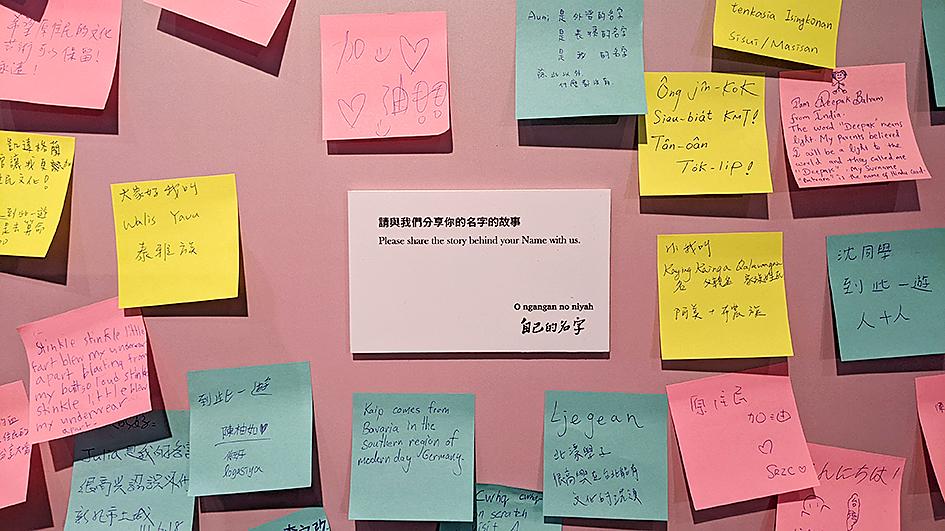

“Bukin means mountain, and my father’s Chinese name includes the character for mountain,” he writes in a display at the O ngangan no niyah (自己的名字, “our own names”) exhibition on indigenous names. His parents’ village, Siaolin (小林), was wiped out by a landslide caused by Typhoon Morakot, and the name further honors his destroyed homeland.

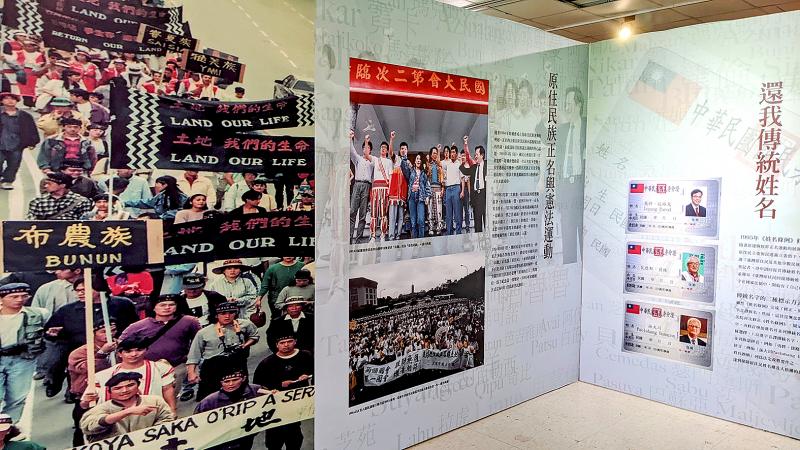

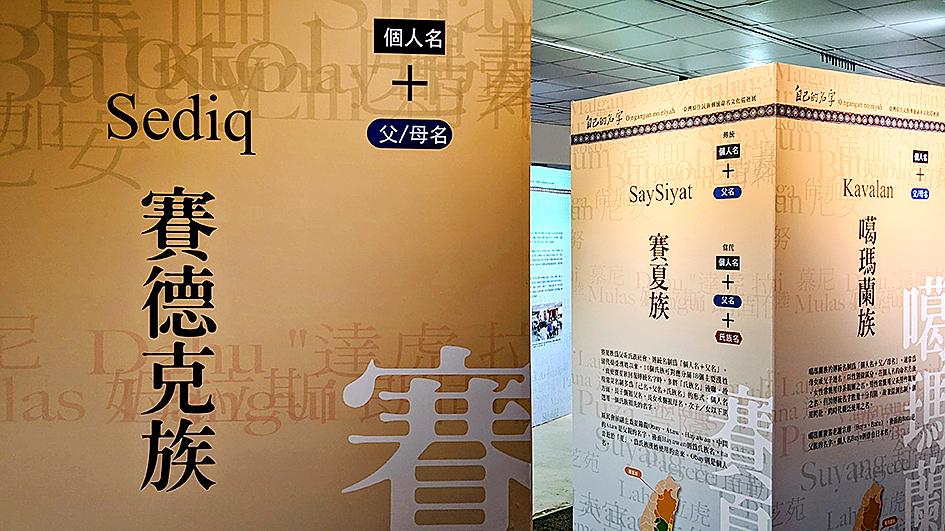

The exhibition, which opened in January at the National Central Library but is currently on view at Ketagalan Culture Center (凱達格蘭文化館) in Taipei’s Beitou District, details the varying naming customs of the 16 official indigenous groups, how they were forced to adopt Japanese and Chinese names and their struggle during the 1980s and 1990s to revert to their “true names.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

It’s an important exhibition that all everyone should see, as there is still a great deal of misunderstanding and discrimination against those who use their indigenous names. Problems range from having trouble receiving packages at convenience stores and being asked by Han Taiwanese if they could use a name that’s “easier to pronounce,” to outright ridicule.

Due to procedural complications and the aforementioned difficulties, according to the exhibit, as of August 2020 only 5.6 percent of Taiwan’s indigenous people have formally changed their names since doing so became legal in 1995.

As the Ketagalan Culture Center is named after the local Pingpu people, it makes sense that a new section on Pingpu names has been added here.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Indeed, there’s enough confusion in mainstream society about how existing indigenous naming systems work, but there’s even less discussion about the experience of modern Pingpu, who have suffered much greater loss of language and culture compared to the 16 groups.

Aidu Timor of the Papora community can trace his family tree back to when they still used indigenous names, but he cannot work out a clear pattern in the naming system. His eighth-generation ancestor used both Chinese and Papora names, but several generations later only Chinese names were recorded.

Mutulavay only adopted her Ketagalan name last year, discovering it in a collection of traditional songs recorded in 1936 by Japanese anthropologists. She even received an Amis name from her friends before she had one from her own people.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“A name is like a symbol of authenticity… For us who are still searching for the traces of our language, we can only yearn for a name,” she writes.

The exhibition is designed as a winding maze, opening with a quote from Hayao Miyazaki’s animation Spirited Away: “Once your name is taken away, you will never find the way home.” Under it is a list of people who lived during the transition between Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule and ended up with three names, such as White Terror victim Uongu Yatauyungana, who had a Japanese name, Kazuo Yata, and a Chinese name, Kao Yi-sheng (高一生).

Visitors traverse the path through history until they reach a still uncertain “exit.” The struggle was not just over personal names, but place names that often glorified the KMT, as well as the government’s pejorative designation “mountain compatriots” (山地同胞).

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The information is detailed and nuanced and easy to understand, and should clear up much of the confusion or misgivings that people may have toward indigenous names.

The last part demonstrates how different each group’s naming systems are, and one of the displayed picture books, What’s Your Last Name? (請問貴姓), explains to Han Taiwanese that not every indigenous person has a surname, and it is definitely not the first character of their indigenous name.

The rest of the museum is a bit underwhelming, with two other exhibits on the second and third floors. Glory of Feathered Headdress (羽冠的榮耀) is a colorfully designed yet disjointed and lacks the celebratory vibe that one would expect to greet the museum’s 20th anniversary. There’s interesting bits and pieces, but the content not coherent or rich enough for viewers to get a true sense of what the place has accomplished over the past two decades. The screening area, which occupies the bulk of the room, curiously plays on repeat one five-minute video about an exhibition from last year.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The Necessity for Craftsmanship (工藝的必要) exhibit is well-presented and offers an array of both designer and traditional indigenous crafts from across Taiwan. It’s worth stopping by if you’re a tourist visiting the hot springs, but don’t expect much of a deep dive.

One would expect more information on the Ketagalan and other Pingpu people who once occupied the Taipei area, but each floor only has a small section in a separate corner dedicated to them, while the rest tries to cover some or all of the 16 official groups, which is impractical in such a small space.

The museum description says that it promotes “all indigenous cultures,” but it would be nice to have a permanent section, perhaps on the first floor, that offers more insight into the people who once occupied the land the museum sits on and gave it its name. Their history is already overlooked enough.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei