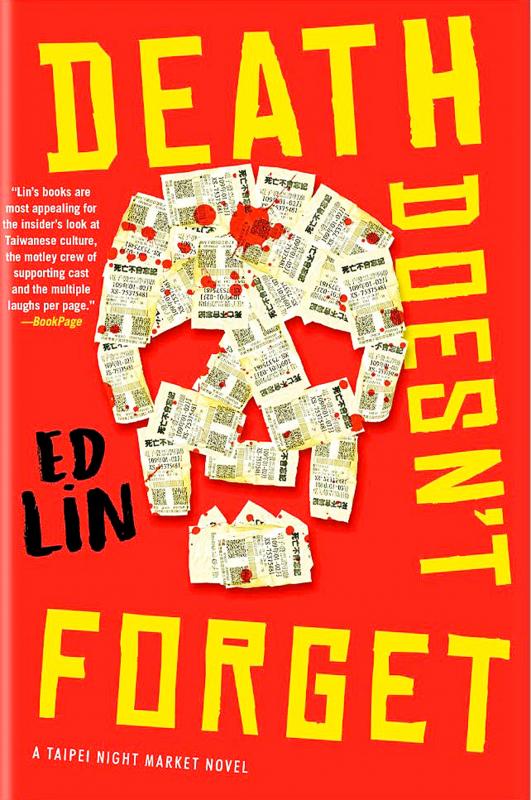

Don’t worry if you missed the first three books of Taiwanese-American novelist Ed Lin’s (林景南) acclaimed Night Market murder-mystery series. I did too, and although I’m still unclear about the former exploits of the Joy Division-loving protagonist Jing-nan who runs a skewer stall named “Unknown Pleasures” in Shilin Night Market, knowing that he’s become somewhat of a local celebrity since the first book will suffice.

Everyone seems to know that Jing-nan at one point fought off armed gangsters by blocking their bullets with only a cast iron pot, and he has mostly given up trying to correct them about what actually happened.

Mild-mannered Jing-nan, who spent two years at UCLA before dropping out due to his father’s illness, is the classic unwilling hero. All he really wants to do is create new delectables (donut skewers with authentic Sri Lankan cinnamon, anyone?) and use his excellent English skills and “Johnny” persona to lure in ridiculously stereotypical — yet totally believable — Western tourists who visit the market.

Jing-nan is conflicted about using this kind of promotional strategy because it goes against his “punk spirit.” But business is good as he finds himself quipping to a visiting family, “Oh, I love Canadians! You’re so much cooler than people from the States!” Like much of the book, this is satirical, but I swear I’ve heard locals express that sentiment out loud more than once.

Lin’s ability to work these gray areas while telling a page-turning story, and on top of that, commenting on Taiwan’s complex social, political and religious past and present as well as interethnic relations — all in a light-hearted yet biting manner — is simply impressive. His liberal yet nuanced use of all sorts of offbeat-but-true Taiwanese idiosyncrasies paints a hilarious yet endearing picture of this country, and these elements will especially appeal to those who have spent time here.

As the series’ title suggests, the book is full of vivid food and cooking descriptions you can almost taste — and not just the good stuff such as Jing-nan’s grandfather’s never-the-same “five-generation-old stew base and basting sauce from a recipe of the Ming Dynasty’s royal court,” but also the microwaved curry cutlet sandwich at FamilyMart for when you’re too hungry to “truly enjoy the act of eating.”

Despite the large amount of information that may be overwhelming to those unfamiliar with Taiwan, it’s skillfully woven into the narrative through the backstories of the diverse cast. The endless array of minor characters provides insight into Taiwan’s social fabric, from the abused, once-stateless Vietnamese bride to the spoiled international school hooligans to the aging, pro-China indigenous veteran who accuses both major parties of letting his people down.

All these details, many of which don’t directly tie in to the plot, can distract from the mystery element. Those looking for a hardboiled crime-solving story will have to sift through long passages before the next clues turn up.

In Death Doesn’t Forget, Jing-nan is reluctantly dragged into trouble again when Boxer, the sleazy boyfriend of his girlfriend’s mother, is murdered after winning big in the reciept lottery. Here lies the book’s only apparent inaccuracy: before his death, Boxer receives his prize at the bank in 100 NT$2,000 bills, which is unlikely as they are barely seen in circulation — and there’s a tax on any prize over NT$5,000, meaning he would not have gotten the full amount.

Anyhow, the shady police captain investigating the matter is soon also found dead. Even though the deceased are unlikeable characters on the surface, Lin still makes them somehow deserving of sympathy by detailing their past, which also shines a light on Taipei’s history, seedy underbelly and cop culture (where street-level closed-circuit cameras are “Taipei’s top crime-fighting tool.”)

Meanwhile, the Austronesian Cultural Festival is about to take place. It seems like a random detail at first, but indigenous issues play a significant part in the plot later.

Jing-nan’s two employees, who reportedly didn’t feature much in previous books, are pushed to the forefront in this one. They each represent a part of Taiwan’s history: Frankie the Cat is a Mainlander orphan who grew up in the military and was jailed during the White Terror, while Dwayne is an indigenous Amis who is bitter about growing up cut off from his culture.

Their stories are poignant and sensitively handled, and beneath the humorous facades are sobering tales of hardship and discrimination. Despite all that’s going on, Lin manages to bring light to Taiwan’s disenfranchised without being preachy or disturbing the flow.

These numerous character sketches may be a bit much to take in at once, but they linger in the mind long after finishing the book. Even though I live in Taipei, I can still picture Lin’s amped-up version of it, slightly shinier and wackier but so familiar at the same time.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger