June 13 to June 19

Despite Taiwan being famous for its oolong tea during the late Qing Dynasty, the Japanese hoped to turn its new colony into “another Darjeeling.” The suggestion was made by the Japanese consul to Mumbai, Go Daigoro, a year after they took over Taiwan in 1895.

Indian Black tea was gaining popularity on the international market after the British systematized and mechanized large scale production in the country’s northeast, causing a steep drop in sales of other varieties of tea from East Asia. Unorganized and uneven production in Taiwan — with many producers cutting corners to save costs — also plagued the local industry, leading the Japanese to install a number of reforms.

Photo: Chen Hsin-jen, Taipei Times

One goal was to successfully grow a variety of black tea that could compete with India. The effort began in 1906, and although most of the crop was exported to Russia and Turkey, the industry didn’t pick up until they discovered in the 1920s that Nantou County’s Yuchi Township (魚池) was an ideal growing location for Indian leaves.

A key person for this success was Kokichiro Arai, who arrived in Taiwan in 1926 and was instrumental in the establishment of the Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute (today’s Yuchi Branch of the Tea Research and Extension Station) on Maolan Mountain (貓?山) in 1936. He became the institute’s head in 1941, and continued to promote and develop the local Ceylon-style black tea despite limited resources during World War II.

Arai stayed on after the war to help the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and is often remembered as the “guardian of Taiwan’s black tea.” He died from malaria on June 19, 1947, but the industry boomed over the years until its decline in the late 1960s.

Photo: CNA

After the devastating 921 Earthquake in 1999, local officials revived the industry in an effort to rebuild the area, and today Yuchi is once again famous for its black tea.

EARLY STRUGGLES

Although there had been small-scale production of black tea in Taiwan during the Qing Dynasty, local farmers prefered Oolong and other varieties. As international competition heated up during the early Japanese era, however, the prestige of Taiwanese tea started to slide. It was overly reliant on the US market, and suffered greatly during tightened restrictions during the Spanish-American War of 1898.

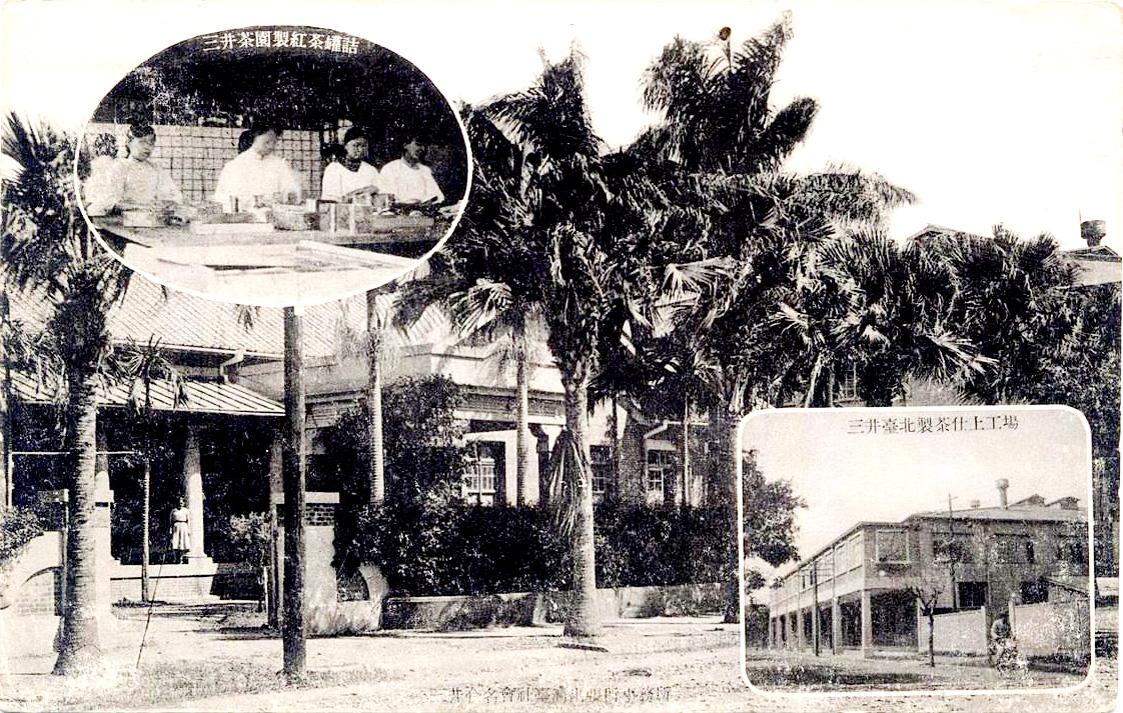

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College Libraries via Open Museum

Su Yu-ting (蘇郁婷) writes in “Marketing Channels and Sales of Taiwanese Black Tea during the Japanese Occupation” (日治時代台灣紅茶的外銷與品飲) that compared to the systematized production of India, Taiwan’s tea relied on manual labor and the goods were often uneven in quality. In 1909, a Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) article blamed the shoddy transport crates, which often broke and spoiled the tea. About 100,000 boxes per year went to waste, the article stated. Fierce local competition also led producers to mix lower grade leaves or other fillers in with the higher-quality variety.

Another problem was that the trade was controlled by wealthy vendors and various middlemen, who gouged up the prices at the expense of farmers. The Japanese in 1901 launched a series of reforms that included organized production by Japanese corporations, mass mechanization and strict quality control.

“The decline of the tea industry is becoming more apparent in recent years,” newly-appointed governor-general Gentaro Kodama wrote in his proposal. “If we allow this to go on for a few more years, it will only continue to tragically decrease.”

The government originally hoped to promote oolong tea, showcasing it at the Paris Exposition of 1900. They opened a tea shop on the fairgrounds and kept a tally of which variety each customer chose, and to their surprise, 42 percent out of the 8,000 or so visitors went with black tea, compared to 28 percent for oolong.

The first research center dedicated to black tea was launched in 1903 what is today’s Taoyuan, using methods and machines imported from the UK. After the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, the Japanese noticed that the Russian POWs had a habit of drinking black tea. They let the imprisoned commanders try the Taiwanese-grown variety to great approval. Selling to Russia was a different story, however, and it would prove the same in other countries over the following decades.

SUCCESS IN YUCHI

At first, most of the larger-scale commercial farming of black tea took place in northern Taiwan by the Mitsui Corporation. They did find success, but it was becoming increasingly hard to compete with India and Sri Lanka. Additionally, northern Taiwan was not suitable for growing the Assam and Ceylon cultivars favored by Western tea-drinkers.

In 1926, the government successfully grew Assam black tea leaves in central Taiwan and noted that the quality was far superior to the local cultivars previously used. A 1933 Taiwan Daily News article extolled the environment of Yuchi, which had just the right altitude, climate and soil.

“In the future, black tea will surely become a specialty product of Taichu Prefecture,” it concluded, referring to what is today Taichung City and County, Changhua County and Nantou County.

Mitsui upgraded its equipment in 1928, and using Indian production methods, created the famous Nitto brand that still exists today.

Unfortunately, India that year banned the export of Assam leaves — which were pricey to begin with — to Taiwan to protect its own industry. This led to the creation in 1936 of the Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute, which focused on developing Assam varieties that could easily be mass-cultivated locally by hybridizing them with Taiwanese wild tea.

The institute also helped develop cultivars brought back from the Thai-Myanmar border by the adventurous “Black Tea Grandpa” Kuo Shao-san (郭少三), which became today’s Taiwan Tea No. 7.

Taiwan’s black tea took off from there, and in 1937 Mitsui’s Formosa Black Tea received high acclaim at a London auction and was enjoyed by the Japanese emperor. Over 5.8 million kilograms of black tea were exported that year. Kuo launched the Puli-based Tung Pang Black Tea Co (東邦) in 1939, and exported his products to Japan and the West. It was one of the businesses revived after the earthquake.

There’s not that much information about Arai’s time in Yuchi. But his dedication and willingness to stay after the war greatly moved new institute head Chen Wei-chen (陳為禎), who erected a monument to him on the institute’s grounds. Arai’s wife and two sons also died in Taiwan, and upon his death, his daughter Reiko returned to Japan and rarely discussed her father’s time here. Her husband and their children visited the monument for the first time in 2008.

The industry continued to do well and expanded under the KMT, but rising wages in the 1960s led to higher costs, and soon Taiwan was no longer able to compete internationally. Meanwhile, tea drinking, which had previously been limited to the wealthy, became a popular activity as the economy grew, but locals preferred oolong over black tea. The industry survived but shrank significantly, and many former fields were turned into betel nut farms.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of