May 23 to May 29

After holding out for seven years, more than 250 Yunlin-based resistance fighters were finally persuaded to surrender in six separate ceremonies on May 25, 1902. The Japanese had subdued most of the Han Taiwanese within six months of their arrival in 1895, but intermittent unrest continued — in Yunlin, the Tieguoshan (鐵國山) guerillas caused the new regime much headache through at least 1901.

These surrender ceremonies were common and usually conducted peacefully, but the Japanese had different plans for these troublemakers. Once the event concluded, they gunned down every single attendee with machine guns.

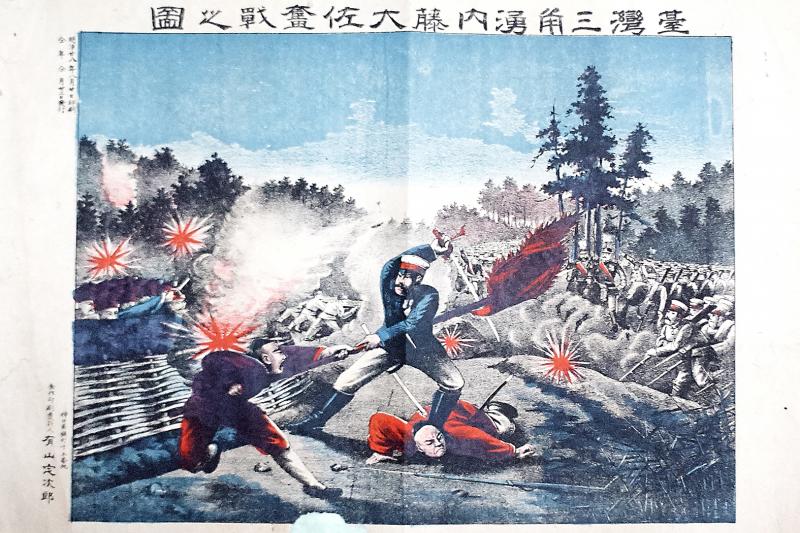

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Only Chien Shui-shou (簡水壽) survived because he left early, but he was caught and executed along with several other leaders three months later.

The remaining commanders either fled to China or went into hiding, drawing an end to this chapter of anti-colonial resistance in the area that included the bloody Yunlin Massacre of 1896, where countless combatants and civilians were killed indiscriminately and thousands of homes were burned down. The event was reported in Hong Kong and British newspapers, causing an international outcry, and Yunlin subprefecture head Yunoshin Matsumura was stripped of his honors and sent back to Japan.

The Japanese took a more tempered approach after that, preferring to force combatants to surrender so they could help fight other rebels, but as the massacre showed, they were still ruthless against anyone who pushed them too far.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

STIFF RESISTANCE

The Japanese arrived in Taiwan in May 1895 after the Qing Empire ceded the island to them through the Treaty of Shimonoseki. After taking Taipei without a hitch, they encountered stiff resistance as they made their way south, with the biggest clash occurring three months later in Changhua, just north of Yunlin.

There were already many armed militias and bandit groups in the Yunlin area as Han settlers frequently fought each other and indigenous warriors, and they made up the bulk of the local resistance. Wu Te-kung (吳德功) writes in his early-1900s account of the resistance that Yunlin strongman Chien Yi (簡義) and several others participated in the defense of Changhua before retreating back south.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After recuperating in Changhua, a contingent of Japanese troops passed through Yunlin without much trouble — at times even welcomed by locals — before stationing in Chiayi’s Dalin (大林) area. However, the misconduct of the soldiers quickly led to local resentment, and the people rose up and attacked them.

With the help of Liu Yong-fu’s (劉永福) Black Flag Army, as well as various local armed groups recruited by Liu’s subordinate, Wang Te-biao (王得標), they managed to drive the Japanese back into Changhua.

Japanese reinforcements soon arrived, and after a few weeks of rest, they pushed south again on Oct. 5, clashing with Wang and Chien’s brigades. The Japanese easily prevailed, and reached Tainan on Oct. 21. Like the previous two leaders of the Republic of Formosa, Liu fled to China without putting up a fight.

MOUNTAIN GUERILLAS

The resistance was far from over, however, as revolts broke out intermittently across Taiwan during the next two decades. Chien joined forces with Ko Tie (柯鐵) and retreated into the Dapingding (大坪頂) mountains of western Yunlin, forming the Tieguoshan guerillas.

Nicknamed the “Iron Tiger,” Ko was a young farmer from Dapingding who had a reputation for violence. He joined Chien’s army and helped him defend Douliu (斗六) before heading for the hills with him. Ko was extremely familiar with the local terrain, and made a name for himself as a shifty combatant who seemed to appear and disappear at will and shoot at the Japanese.

On June 12, 1896, a Japanese-owned shop near the Douliu police station was robbed in the middle of the night. Matsumura was furious. The police rounded up more than 20 people who were suspected to have ties to the Tieguoshan rebels, and found out where they were hiding.

After half of the unit they sent to investigate Dapingding was wiped out, the Japanese began amassing troops in Douliu in preparation for a major assault. Convinced that the locals were in cahoots with the rebels, Matsumura declared that “there are no good citizens in Yunlin” and launched a bloody indiscriminate campaign in the villages near the mountain. Thousands of houses were burned over a week, and the death toll varies from 700 to tens of thousands.

The Japanese thought this would scare the rebels into giving up, but instead it attracted more fighters to their side. They launched an offensive on June 28, reaching Douliu in three days as their numbers grew, many of them civilians armed with farming tools. Matsumura fled to Chiayi, and rebels entered Nantou and pushed as far north as Taichung.

The Japanese quickly struck back, this time with strict instructions not to harm anyone who was unarmed. By July 25, the resistance was crushed.

BLOODY SURRENDER

Due to international pressure, the government decided to employ loyal Taiwanese elites such as Lukang’s Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮) to persuade the rebels to surrender. Chien answered the call on Oct. 5, 1896, upon which Ko became the leader of Tieguoshan.

Chien was awarded a gentry medal and a minor local official position. He died from illness a year later.

Ko refused to give up and continued raiding the Japanese over the next year. After losing four more battles, he also turned himself in in March 1899. However, unrest continued in Yunlin over the next two years, and Japanese officials finally had enough. On May 25, 1902, they gathered over 250 rebels and had them formally surrender in six ceremonies across the subprefecture.

Ke Kuang-jen (柯光任) writes in “Matsu Legends in the 1895 Anti-Japanese War and Structural Amnesia” (乙未抗日媽祖傳說與結構性失憶) that in addition to the persistent unrest, local officials were annoyed that these surrendered “bandits” were given all sorts of privileges. After seven years, two of Yunlin’s major rebel commanders were still at large, and subprefecture officials decided to revert once more to extreme measures.

The surrendering fighters each wore a white flower on their chest, the size of it indicating their rank in the resistance army. At the end of the ceremony at Douliu, officers arrived under the guise of searching for weapons. The rebels attempted to fight back for the last time, but the soldiers and policemen were already in position to open fire.

There appeared to be no repercussions for this act. The Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) claimed that the rebels tried to start a riot, and that was that. It would not be the first time they used this tactic either.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of