May 2 to May 8

In 1898, the all-male Tainan Mission Council was upset that female missionaries were carrying out projects without their consent.

The Presbyterian Church of England began sending single professional or semi-professional women abroad in 1878. There were three of them in Tainan: Joan Stuart, Annie Butler and Margaret Barnett, who took turns running the Sinlou Girls’ School (新樓女學校, today’s Chang Jung Girls’ Senior High School). Opened in 1887, it was the first Western-style school for women in southern Taiwan, and the only admission requirement was no foot-binding.

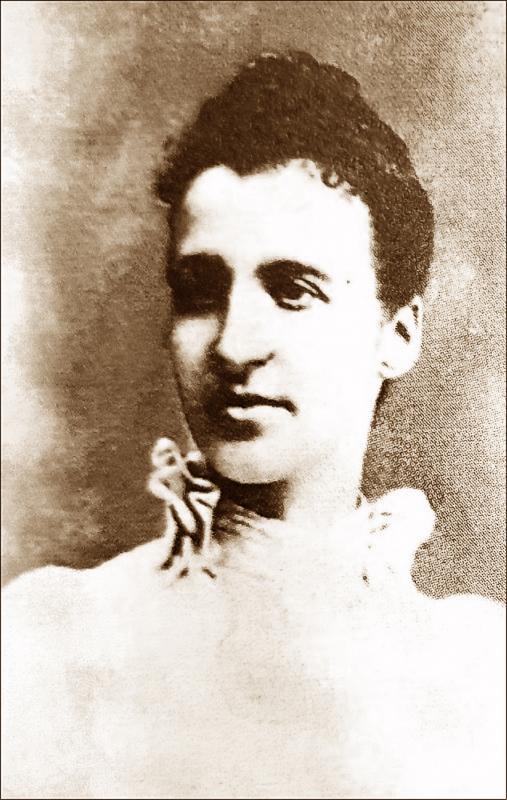

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Reverend William Campbell wrote a 11-page letter to the trio on behalf of the council, accusing them of various misdeeds over the previous six years and asserting that the council alone exercised authority in the mission field. They didn’t like that Butler and Stuart left the missionary compound to live with locals without their permission, that they served as midwives and that they opened the Women’s Bible School without the council’s approval, among other complaints.

The women responded that they had been carrying out “ordinary work,” which was “the teaching of women and girls and ways by which we can bring them under the power of the Gospel,” adding that they saw no need to report to the council and that their sole authority was the Women’s Missionary Association (WMA) in London, writes Rosemary Seton in the book, Western Daughters in Eastern Lands: British Missionary Women in Asia.

A compromise was reached and the three carried on until Stuart and Butler moved to Changhua in 1910 and eventually returned home after retiring. With no more family left in Scotland, Barnett remained in Taiwan after she stepped down in 1926 due to health issues. She continued to evangelize and teach locals how to read and write in romanized Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) until her death on May 8, 1933.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

She translated and wrote several essays and novels in Taiwanese, including a compendium on notable female missionaries, which she completed with Butler.

FIRST FEMALE AGENTS

After a two-century absence, Christian missionaries began returning to Taiwan in the 1860s when the ruling Qing Dynasty opened the ports of Tamsui and Kaohsiung to foreigners. The Presbyterian Church did not have single female evangelists then, and work with local women and girls was carried out by the wives of missionaries.

Photo courtesy of Ministry of Culture

Eliza Cooke Ritchie was one of these wives, arriving in 1867 with her husband Hugh. Education for girls was very limited in those days, and in 1879, Hugh requested the Tainan Mission Council to build a girls’ school and invite professional female missionaries to run it. This was five years before George Leslie Mackay started Taiwan’s first institute for girls in Tamsui, but unfortunately Hugh died later that year from malaria.

Eliza stayed in Tainan to continue Hugh’s work, and requested to be ordained as Taiwan’s first female missionary through the WMA in February 1880. In December 1880, the WMA sent E Murray (full first name unknown) to help Eliza in Tainan, but she only stayed for three years before moving to China.

Eliza continued her efforts to build the school while teaching local women how to read the romanized Bible. However, a National Taiwan History Museum article states that even though she managed to obtain enough funding, the construction was hampered by resistance from conservative local elites and didn’t break ground until 1883.

Photo courtesy of Ministry of Culture

Eliza fell ill in 1884 and left Taiwan, never getting to see the Sinlou Girls’ School’s completion by Stuart and Butler, who arrived in 1885 after the conclusion of the Sino-French War made it safe to travel again.

Seton writes that British men and women were not used to working as colleagues then, and many conflicts arose. The church at first mandated that the missionaries follow the orders of the all-male local Presbyterian councils. But by the 1890s, the women were mostly working independently, only bringing any “extraordinary and special matters” to the council.

While mediating the row between the Tainan council and the three women, the London Missionary Society suggested including females on the council as a solution, but even the WMA thought it was too radical of a solution.

“Not every disciple has taken in the New Testament teaching that ‘male and female are all one in Christ Jesus,’” WMA secretary Elizabeth Mathew commented, fearing that there would be “great trouble” with the men on the council if this was suggested. Instead, the men and women met separately and sent each other copies of their respective meetings, Seton writes. They would not sit together on a committee until decades later.

EDUCATING WOMEN

According to the church, Stuart was the nation’s first “midwife missionary.” She saw firsthand the need for midwives after seeing many women suffer during childbirth because they were not allowed to see a male doctor. She and Butler traveled to Kaohsiung to train with W. W. Myers, a medical officer with the British Customs Office, and obtained their licenses from back home.

They were joined by Barnett in 1888, who hailed from Aberdeen, Scotland. Barnett had just been in Taiwan for a week when she received news of the death of her two brothers, but she persisted and focused on learning Taiwanese so she could start preaching.

The three took turns running the school, while the other two would go into the community or visit patients at the church’s hospital. The school’s first students were mostly indigenous.

In addition to religious studies, the school taught reading, writing, arithmetic, geography and practical skills such as sewing. Barnett writes in an 1893 Taiwan Church News article titled “Girls’ schools” that the school was at full capacity with 23 students. She lamented that this covered less than 10 percent of the girls belonging to the various churches in Taiwan, and pleaded for headquarters to build more girls’ institutions in Taiwan.

Barnett started the Women’s Bible School in 1895 for older students, many of them illiterate. Jane Anne Lloyd joined their ranks in 1903 and was appointed principal of Sinlou, allowing Barnett to devote her attention to running the Women’s Bible School.

In 1910, the Bible School only had seven students, but according to Chen Mei-ling’s (陳美玲) “Research on the first female theological school in Taiwan” (臺灣第一所女子神學校之研究), more than 100 students passed through its halls over three semesters in 1925. However, Barnett was not happy.

Earlier students such as Chiu Chin (邱進), who graduated in 1916, actually completed the two-year program and devoted themselves to the church. But by the 1920s, most stayed just a semester or two and transferred to Sinlou so they could rise through the formal education system.

Barnett lamented in 1926 that her students saw the school as a gateway to furthering their studies, and that few wanted to become evangelists. She retired later that year at the age of 68.

The school shut down with Barnett’s departure, but it was reorganized two years later as the Women’s Bible Institute with Lloyd serving as principal.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern