When Dongi Kacaw was asked to write three articles about indigenous wild greens 26 years ago, she responded with surprise.

“I don’t know how to do that,” she says. “I just know how to eat them!”

But after returning to Hualien, the indigenous Pangcah (Amis) now known as the “godmother of wild greens” (野菜教母) could not stop thinking about the request. She couldn’t find anything in the library about the plants she grew up with — so she went home to ask her parents.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“I started taking photos, visiting sunset markets, going foraging with old people … I completely threw myself into the project like a madwoman,” Dongi says.

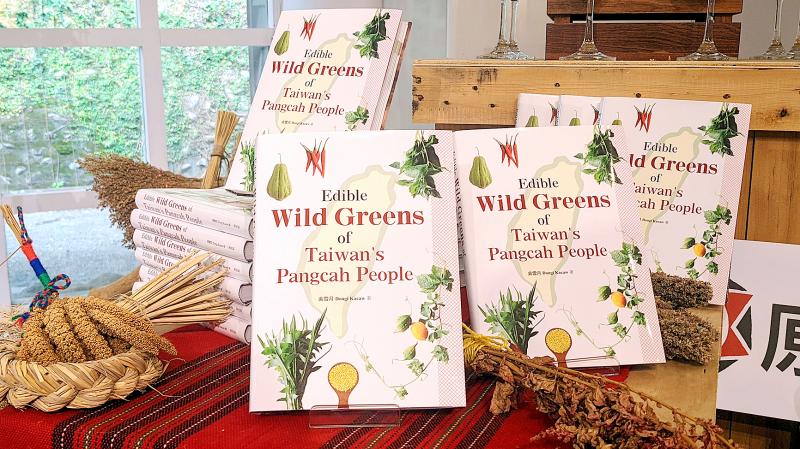

She ended up submitting 36 articles to Taiwan Indigenous Voice Bimonthly (山海文化), which became the basis for her 2000 book, Edible Wild Greens of Taiwan’s Pangcah People (台灣新野菜主義). It was unexpectedly popular, and was reprinted 18 times and translated into the Pangcah language last year. On Tuesday, the English-language version of the book was released at the Hualien Indigenous Wild Vegetables Center (花蓮原住民族野菜學校), where Dongi is the principal.

Edible Wild Greens features 63 local entries organized by parts of the plant, as well as six contributions from Hawaii, Indonesia and India that were not included in previous editions.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“The purpose of this book is not only to impress on people how many types of edible plants there are in the world, but also to explain, from the perspective of the wild greens culture of the Amis community, the importance of wild plants to our lives,” the book’s introduction states.

Dongi hopes that the book will help facilitate more international exchanges on traditional food culture during events such as the Austronesian Forum and the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

“We share many similar food items with other Austronesian and Southeast Asian peoples, but we may use them differently,” Dongi says. “We can show them how we forage, and then we can exchange and generate new ideas.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

FIELDS AND MOUNTAINS OF EDIBLE GREENS

Despite being best known for her work in studying, promoting and preserving her people’s wild greens, most visitors enthusiastically greet Dongi as jiaoguan (教官, military instructor), referring to the retired lieutenant colonel’s old job at National Hualien University of Education.

“When we Pangcah people look at plants, we always first identify which part is edible,” Dongi says. “We’re the most prolific at eating wild greens in Taiwan. There are fields and mountains full of edible plants here, but most people don’t know about them.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

If the Pangcah are unsure about a plant, they’ll pick a tender leaf and lick it with the tip of their tongue.

“If there’s no numbing or tingling feeling, then it’s a wild green,” she says.

Today, Dongi runs a wild vegetable center, which opened in December 2020 with government support. It hosts exhibitions, tours and workshops that promote these plants, with the goal of preserving indigenous biodiversity. Many wild plants she ate as a child have disappeared, and for the past decade she’s been trying to restore them and preserve the seeds.

Photo courtesy of Hualien County Government

She’s also led a number of international exchanges as head of the Taiwan indigenous people’s chapter of the Italy-based Slow Food International, which aims to prevent the disappearance of local food cultures and traditions and promote “good, clean and fair” eating. They’ve participated in numerous events abroad, and also host an annual international indigenous slow food forum in Hualien.

As Taiwan’s indigenous people interact more with the rest of the world, especially with their Austronesian relatives and other indigenous groups, it became increasingly crucial to translate Edible Wild Greens of Taiwan’s Pangcah People into English.

TRANSLATOR NOTES

Cheryl Robbins, a licensed tour guide whose work includes the Foreigner’s Travel Guide to Taiwan’s Indigenous Areas series, says she offered to translate the book after seeing Dongi give the Chinese version of the book to several Maori visitors from New Zealand a few years ago.

She credits book editor (and Taipei Times contributor) Steven Crook for alerting her to areas that needed further clarification and elaboration.

“The reader may not have that much experience in indigenous communities,” says Robbins, who has been working with indigenous communities for decades. “[Crook] was good at pointing out when I needed more information and when I needed to simplify and clarify.”

Robbins, whose background is in zoology, was worried that her lack of familiarity with botany would be a challenge, but besides a brief scientific introduction to start each entry, she found the prose quite conversational.

“[Dongi] talks about how her mother and grandmother used [a plant], or that they went to someone’s house and cooked it a certain way,” Robbins says. “It’s tied to her experience growing up in an Amis community, and during that time Taiwan was not very economically well off, so wild greens really did play an important part in their diet.”

Robbins hopes that Dongi continues to produce material in English, and even offer activities and classes in the language.

“She’s a national treasure in terms of her knowledge of wild greens,” she says. “I hope this will be a good first step toward being able to share more of this knowledge not just with indigenous people, but people from various cultures, countries and backgrounds.”

NEW EDITION?

Dongi is already thinking of revising the book, as much has changed for her in the past 22 years. She wanted a more extensive international section in this latest release, but she says she had a hard time finding writers within a short time frame.

“I also didn’t think about the deeper cultural implications when I wrote the stories,” she says.

She’s pondering how to rearrange the book according to the Pangcah knowledge system to “reclaim our food sovereignty,” although she hasn’t entirely figured out how.

“Why do we have to follow the scholarly categorizations of roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits?” she asks. “Our people classify some plants according to their taste. We need to quickly sort out and systematize this knowledge.”

Dongi also hopes to include recipes in the book.

There are still some lingering issues with indigenous foodways that Dongi hopes to address. Only in 2019 was the Forestry Act (森林法) amended to allow indigenous people to collect forest resources on public land for personal use without worrying about being arrested.

“We had to covertly harvest yellow rotang palms for their hearts before,” she says. “How can a Pangcah not forage for wild greens?”

She also spoke emotionally about the restrictions on private alcohol brewing.

“This is our culture, our way of life. We have to work hard to change this situation.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of