April 18 to April 24

On the surface, there was nothing controversial about Wen Hsia’s (文夏) 1961 song Mama, I’m Brave (媽媽我也真勇健). In fact, the lyrics — about a young man missing home during his military service — seemed like the morale-boosting tune that the government would favor.

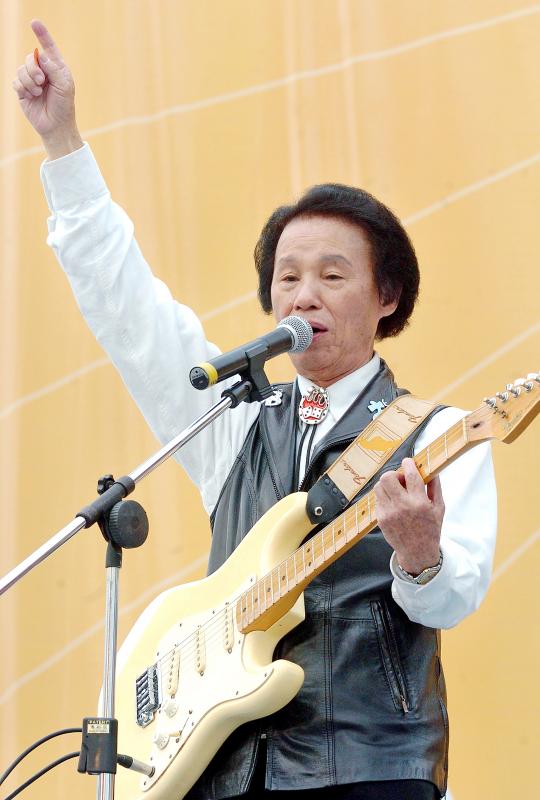

However, the authorities banned it shortly after its release. The ban was lifted in 1991, making Mama, I’m Brave the longest-ever prohibited Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) song. Wen, who died on April 6 at the age of 93, was a favorite target of the censor, holding the nation’s record with 99 forbidden songs.

Photo courtesy of Hua Feng Culture

Mama, I’m Brave was banned because it was originally a Japanese military song about a Taiwanese-born soldier fighting against China during World War II. Although it was composed by revered folk singer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), authorities didn’t like it because the last line portrayed the Japanese army victorious against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

Wen later argued in an interview uploaded to the Taiwan Popular Music Database (台灣流行音樂資料庫) that he was supporting the government’s anti-colonial efforts by converting Japanese songs into Taiwanese because most people on Taiwan in the post-war years didn’t understand Mandarin.

“I took those songs and made them Taiwanese because under Republic of China (ROC) rule it was taboo to sing in Japanese. I call that patriotism, but the Ministry of Education didn’t think so,” he said referring to the agency responsible for censorship at the time.

Photo: Chen Yi-kuan, Taipei Times

Prohibiting the song, however, was pointless. Mama, I’m Brave sold well — especially pirated versions of it. And, to the chagrin of the government, the song was popular with soldiers.

For each song banned, Wen recorded a dozen more, churning out over 1,200 during a career that spanned seven decades. Many were “mixed-blood songs” (混血歌曲) — Japanese melodies with Hoklo lyrics.

“Many modern Mandarin hits are covers of Japanese songs,” Wen says. “In that sense, I was quite progressive.”

Photo courtesy of Fu Jen Catholic University Department of Music

GOLDEN DECADES

Wen was born Wang Jui-ho (王瑞河) in Tainan’s Madou District (麻豆) in 1928. His family ran a successful clothing shop, so he was able to attend junior high at a music academy in Tokyo. After returning to Taiwan, he formed various bands with his classmates and performed during school breaks.

He remained active with the Wen Hsia Hawaii Band (文夏夏威夷樂隊) after graduation and moonlighted in other larger groups. Impressed, the newly-formed Asia Recording Co (亞洲唱片) produced his song Drifting Woman (漂浪之女) as its debut record. Wen also formed the Wen Hsia Four Sisters band with Wen Hsiang (文香), Wen Ying (文鶯), Wen Chueh (文雀) and Wen Feng (文鳳).

Photo courtesy of Wen Hsiang

The Taiwanese-language music scene thrived in the 1950s and 60s, but went into decline with the KMT’s sinification policies and focus on Mandarin.

The television boom in the 1970s was another blow to Taiwanese-language pop since the government placed increasing restrictions on the screen time of Taiwanese songs.

Fortunately, Wen was able to transition to the movie business. He starred in the 1962 box office hit Taipei Nights (台北之夜), where he played A-wen, a wandering singer. Wen formed his own production company in 1964 and reprised the role for Brother A-wen (阿文哥), a film that also included the Four Sisters. The character A-wen appeared in at least 10 other films.

Photo courtesy of Wen Hsiang

Wen wrote, produced, starred in and composed the music for several movies, all while touring the nation to promote his music due to the television restrictions. Sadly, public interest in Taiwanese cinema rapidly declined, and only one work, Goodbye Taipei (再見台北, 1969), survives, having been restored by the Taipei Film Institute.

TOO DEPRESSING?

The government in the early 1970s stepped up its censorship of songs, especially those that featured vulgarity or were critical of the government. The censor took aim at Wen’s songs because they didn’t sufficiently boost morale at a time when the KMT felt that people should be focusing on defeating the communist bandits across the Taiwan Strait.

Photo: Liao Chen-hui, Taipei Times

One of Wen’s best-known songs, My Hometown in the Sunset (黃昏的故鄉), was banned for “corroding the military spirit by evoking homesickness,” while Mama Please Take Care of Yourself (媽媽請妳也保重) was “deflating and bad for morale.”

Interestingly, singer Chi Lu-hsia (紀露霞) in 1965 re-recorded Mama, I’m Brave for a movie with new lyrics about familial love and a much slower arrangement. It was spared the axe.

In an op-ed in NewTalk (新頭殼) last week, commentator Kuang Jen-chien (管仁健) writes that it was the content of Wen’s movies that the authorities especially disliked. They wanted to portray Taipei as a prosperous and harmonious city ready to take back the Mainland. Wen’s films often portrayed it as a dark, treacherous urban jungle that swallowed up people from the countryside.

By the late 1960s, three of the Wen sisters had married or left the band. Only Wen Hsiang remained; she married Wen Hsia and the two remained lifelong partners.

When Japan broke relations with Taiwan in 1972, Wen pretty much had to stop performing because authorities banned all Japanese songs, including mixed-blood songs, in response. So Wen moved to Japan.

“In Taiwan, they made it hard for us to sing Taiwanese songs. In Japan, the Japanese thought that I was a fake Taiwanese because I spoke Japanese so well, and they often asked me to sing in Taiwanese to prove it,” he told Taiwan Panorama magazine in 2011.

In 2017, an 89-year-old Wen Hsia charmed the crowd at a concert marking the 30th anniversary of the lifting of martial law.

Wen Hsia told the Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) that he felt elated being able to sing formerly banned songs on this particular date, adding, “and the person who banned my songs failed to be elected president,” a not-so-subtle dig toward James Soong (宋楚瑜), the former head of the Government Information Office — the agency charged with censoring books and music after 1973.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.