April 11 to April 17

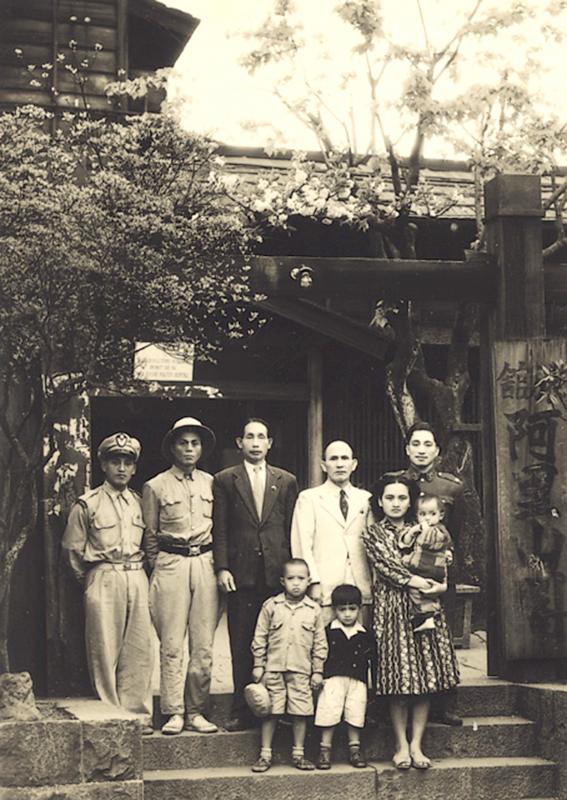

Losing Watan and Uyongu’e Yatauyungana first met in 1935 at a government-organized gathering of 32 young indigenous leaders from across Taiwan. The group bonded over the prospect of building a better future for their communities.

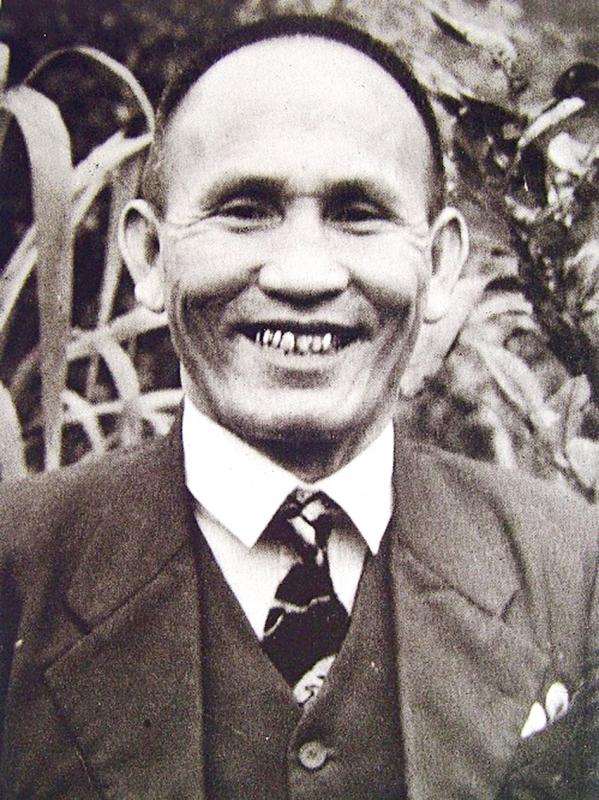

After the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over in 1945, these Japanese-educated professionals were eager to work with the new government to modernize their villages, as well as promote indigenous rights and autonomy. Losing, an Atayal, became the only indigenous member of the Taiwan Provincial Assembly, while Uyongu’e served as chief of what is today’s Alishan Township, home to his Tsou people.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On April 17, 1954, Losing and Uyongu’e were executed along with Atayal policeman Kao Tse-chao (高澤照) and Tsou leaders Yapasuyongu Yulunana, Mo’e Peyongsi and Fang I-chong (方義仲). They had been found guilty of corruption and sedition, a common White Terror charge. Losing was originally sentenced to 15 years, but army chief of general staff Chou Chih-jou (周至柔) condemned him to death while reviewing the verdict, which was personally approved by president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

The group was accused of forming a “communist bandit” cell under Beijing’s directives and recruiting young indigenous men to support a potential Chinese invasion.

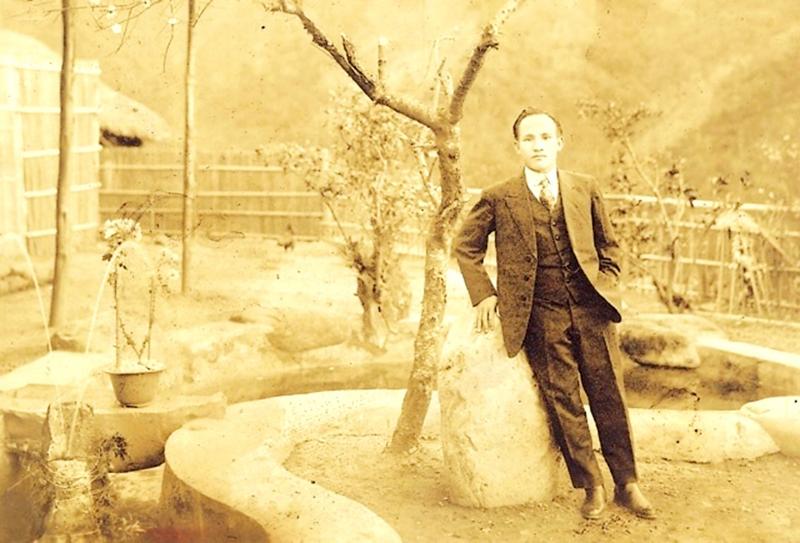

It was a tragic end for these men, who were among the first generation of their subjugated peoples to receive a formal Japanese education. Losing’s father, Watan Mrhuw (or Watan Syat in some sources), waged a years-long rebellion in what is today’s Sansia District (三峽), and as condition for his surrender, 10-year-old Losing was sent to a school for indigenous children and renamed Saburo Watai. He changed names again under the KMT, and it was Lin Jui-chang (林瑞昌) who was put to death in 1954.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While communist agents tried to recruit Losing, there was little evidence that he agreed to work with them. Most sources state that he incurred the wrath of the authorities due to his advocacy for indigenous autonomy — most notably a campaign demanding the government return the land his people lost to the Japanese, which almost sparked a riot in 1948.

ASSIMILATION POLICY

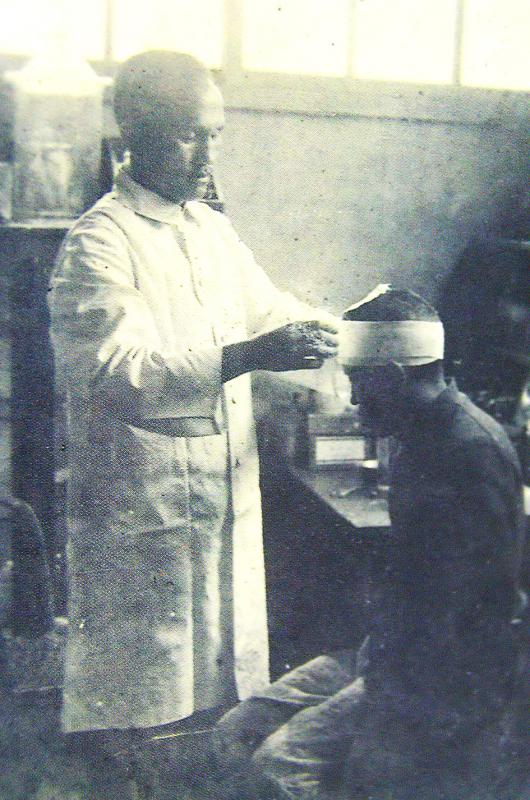

It took the Japanese two decades to completely subjugate Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and gain control over the entire island. After each group’s defeat, the Japanese built police stations, schools, clinics and other institutions in their area to assimilate them into productive, loyal citizens of the empire. They were discouraged from traditional practices and organized into farming communities.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Unlike the more hostile groups to the east, the Tsou established relations with the Japanese early on. The first school for indigenous children in Taiwan was set up in 1904 in Tapanu village, and Uyongu’e was one of the graduates.

In 1909, Watan Mrhuw sued the government for peace, changing Losing’s life forever. He went on to complete medical school in Taipei and returned home at the age of 22 as a public physician. He helped improve healthcare resources in the area and worked with the state to build roads and other modern infrastructure.

Colonial rule was often exploitative and humiliating, however, and in 1930, the Seediq of Wushe (霧社), once considered a model community, revolted after years of mistreatment. The incident garnered much domestic and international criticism, and the colonial government was forced to tone down the exploitation and switched gears to “incorporation and assimilation.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The “savage” designation was removed; they were now the Takasago people, named after an old Japanese name for Taiwan. New policies were promulgated in 1932 to “educate” them so they could enjoy prosperous lives as fellow citizens “bathing in the holy benevolence [of the emperor].”

The Japanese organized indigenous youth groups in each community, led by “visionaries” handpicked by the area’s local police. The 1935 symposium was composed of these leaders, who were groomed to become respected figures who could serve as a bridge between the authorities and their communities.

Their presentations all revolved around furthering assimilation: Uyongu’e, who was 28, spoke of encouraging his community to grow more bamboo, and to give up the practice of burying their dead indoors and establish public cemeteries. Losing, 37, argued that if his people were allowed to keep their guns, it would be hard to launch policies to eradicate “backward habits.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

INDIGENOUS AUTONOMY

Losing had high hopes for the KMT at first, as they promoted democracy and equality. But not only were Taiwan’s indigenous people again treated as third-class citizens, their standard of living actually deteriorated under the new regime.

In the provincial assembly, Losing often advocated for indigenous rights and urged the government to develop and employ more indigenous talent. He often criticized the government and put forth numerous proposals to improve their social and economic conditions.

Historian Wu Jui-jen (吳睿人) writes in a paper on the executions: “Although [Losing] went to great lengths to stop his community from rising up during the 228 Incident [in 1947], whenever it came to the welfare of his people, he became a fearless dissident who risked his life to oppose the authorities.”

Since it was the Japanese who took his people’s land, he hoped that he could get it back under the KMT. “The ‘retrocession of Taiwan’ should also include us reclaiming our homeland, otherwise what joy can we feel in this ‘retrocession to the motherland?’” he wrote in a petition signed by over 100 compatriots and delivered in June 1947, months after the mass unrest was suppressed.

Uyongu’e also wanted autonomy. After he and his comrades clashed with government troops in Taichung following the 228 incident, he wrote and sent a letter to indigenous leaders calling for a meeting to discuss the establishment of a “high mountain autonomous zone.” Wu writes that he never acted on the idea due to the political climate and turned his focus to boosting the economy of the Tsou people by establishing the Xinmei Farm (新美農場).

As the Chinese Civil War neared its conclusion in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party recruited Taiwanese members such as Tsai Hsiao-chien (蔡孝乾) and attempted to set up cells across the nation to subvert the KMT. Dissidents like Losing were prime recruitment targets, and he met with communists several times.

A government crackdown in late 1949 sent numerous communist agents fleeing into Alishan, and while there’s no evidence of Uyongu’e joining them, he interacted with them and allowed them to operate in the area. After the government cleared out the cells in the area, he and Yapasuyongu turned themselves in and swore to repent with Losing acting as guarantor.

In September 1952, the government lured Uyongu’e and Yapasuyongu to town under the pretense of a security meeting, arrested them for corruption and carted them off to a military prison in Taipei. Losing, who had financial dealings with the two over Xinmei Farm, was nabbed in November.

But over the two-year investigation, corruption charges evolved into charges for communist rebellion, leading to another tragic chapter in White Terror history.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades