March 28 to April 3

The Taipei City Government was in a panic. There were only six days left until the March 29, 1994 grand opening of Daan Forest Park and officials had yet to resolve an intense dispute — one that had gone on for two years — over whether to keep a large Guanyin statue on the park’s northwest corner.

Buddhist Master Shih Chao-hwei (釋昭慧) and independent legislator Lin Cheng-chieh (林正杰) were on day five of their hunger strike to save the statue, vowing to “defend the statue to the death” and rally their supporters to form a massive human barrier around it on opening day.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The government had hoped that the influential Fo Guang Shan Monastery could persuade the protestors to negotiate. But on the night of March 23, the monastery’s founder, Master Hsing Yun (星雲法師), announced his full support for the protest, saying that he would mobilize 325 tour buses full of people.

The city’s final offer was to keep the statue as public art, as long as believers refrained from using it for any religious activities. The protestors accepted and called off the hunger strike.

On the morning of March 27, 1994, Master Hsing Yun symbolically donated the Guanyin to then-mayor Huang Ta-chou (黃大洲) in a brief ceremony, finally drawing a close to the debacle.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Although the crisis was averted, the park’s grand opening was a disaster anyway. A Chinese Television Service (華視) video on YouTube shows hapless visitors trudging through ankle-deep mud and construction debris. And despite the celebratory events throughout the day, Taipei’s largest green space was painfully incomplete. The restrooms weren’t even functional yet.

There was still a ways to go before what was nicknamed “Mud Park” (泥巴公園) could live up to its promise as the “lungs of Taipei.”

LONG TERM PROJECT

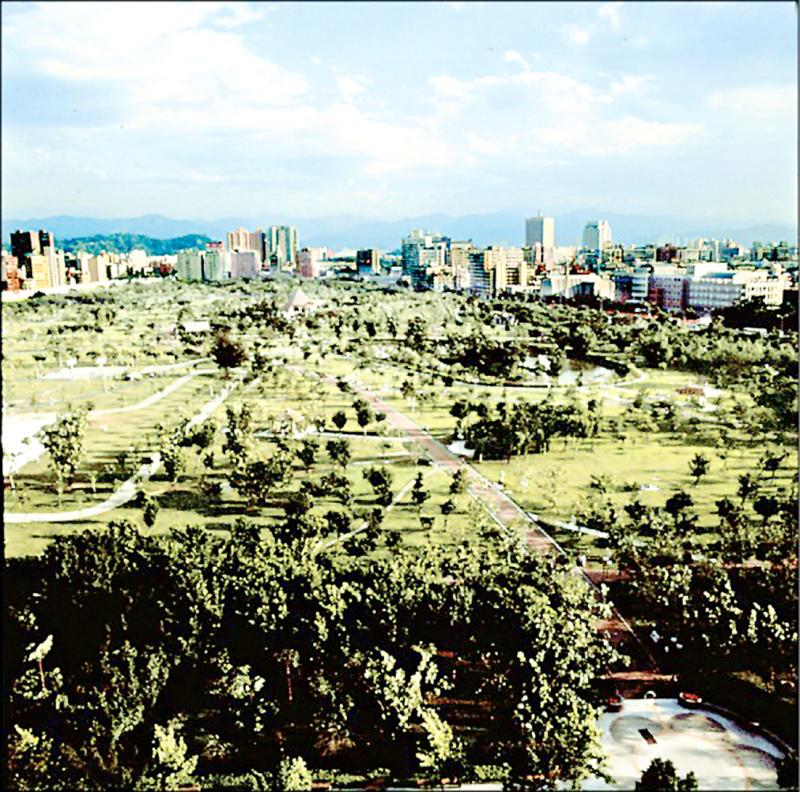

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Daan Forest Park was a project more than 60 years in the making. In 1932, the Japanese set aside 17 locations in Taipei to serve as future urban parkland. Each location was identified by number, and up until the 1990s, Daan Forest Park was called “Park No 7.”

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) used most of these open areas for military purposes when they first arrived after World War II. Park No 7 housed two military dependent villages, various military facilities including a radio station, and the International House of Taipei. Illegal squatters, most of them refugees from the Chinese Civil War, also settled here, and up to a few thousand people may have lived there. The settlement continued to expand throughout the years as young people came to Taipei from the south to seek their fortunes.

The International House of Taipei’s gymnasium, located on the corner of Xinsheng South Road and Xinyi Road, was a hotspot for concerts, sports matches and movie screenings. It hosted several Miss China beauty pageants in the 1960s.

Photo courtesy of Chung Yung-ho

In 1984, the government briefly mulled building a 30,000-capacity stadium on the land instead of a park, but this was met with protests by environmentalists who advocated more green spaces in Taipei. The city decided on a “forest park” in 1989.

Life was not easy in these settlements, as shown in the 1983 movie Papa, Can You Hear Me Sing? (搭錯車), but people refused to leave when the government tried to relocate them. Their fierce resistance plays a significant part in the film, and a major character dies in a clash with the authorities. The city prevailed, and on April 2, 1992, they tore down the International House.

These residents generally supported the removal of the statue, as they found it unfair that it was allowed to remain while they lost everything. Many of them were Christian, and the demolition of the park reserve’s places of worship also drew the ire of non-Buddhist groups.

STATUE OF CONTROVERSY

Completed in 1985 by renowned sculptor Yuyu Yang (楊英風), the statue has been mired in controversy since its inception.

In 1979, Da Hsiung Monastery (大雄精舍) founder Chiu Hui-chun (邱慧君) reportedly received a message in a dream to build a new temple next to the International House of Taipei. Landowner Lin Tsung-hsien (林宗賢) was happy to allow it, but the government was reluctant to allow a structure when clearing the current land was already a problem.

The Buddhist community rallied and secured political support, reaching a deal where Chiu could build a statue for simple worship, but not a temple. The monastery promised not to interfere with Park No 7’s development and obey all government requests during planning and construction. This clearly wasn’t the case later.

The statue attracted many worshippers, who planted a bamboo forest around it as a natural house for it. Huang recalls that the monastery ignored the city’s repeated requests to move the statue, and they left the structure standing during the 1992 demolitions due to its sensitive nature.

This sparked the struggle that went on for years, and it didn’t help that the government kept changing its stance under pressure from whichever side had the upper hand. Removal advocates were dominant until June 1993, when someone splashed acid and feces on the statue. This sparked outrage in the Buddhist community. Within a week more than 10,000 signatures in support of the statue were gathered and brought to city hall by Da Hsiung Monastery abbott Master Ming Kuang (明光法師) and supporting politicians.

In September, Huang decided to retain the statue as public artwork, noting that along with the bamboo forest it would be a nice addition to the park. The statue would be fenced off with barriers, plants and flowers to prevent people from approaching.

Removal advocates were furious and launched an even stronger campaign. Within two months Huang ordered the monastery to remove the statue by the end of March 1994.

With a little over a month until the park’s grand opening, supporters launched the “Guanyin Don’t Go” campaign, which was joined by many Buddhist groups across the nation. More and more politicians also got on board, and the city was running out of time.

“Of course there was immense pressure,” Huang says years later in “A Study on Power and How it Shapes Spaces” (權力與空間形塑之研究) by Liao Shu-ting (廖淑婷). “Three hundred tour buses would paralyze Taipei’s traffic.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson