I met Stan Lai (賴聲川) in 2004 when he was directing a production of Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni in Taipei. I asked him what he thought of the opera’s protagonist. Lai replied that he was a liberator who freed women of their sexual inhibitions and led them into a new kind of independence.

I disagreed profoundly. Don Giovanni is a serial seducer who kills the father of one of his victims in the first five minutes of the opera and is dragged off to hell at the piece’s end.

There is a great deal of comedy in the opera, but it has always seemed to me that the music is more memorable if we keep in mind the Don’s essential selfishness and cruelty. Lai clearly disagreed.

Lai also told me that initially he hadn’t been drawn to opera as a genre, but had been won round by the intensely dramatic nature of this particular work.

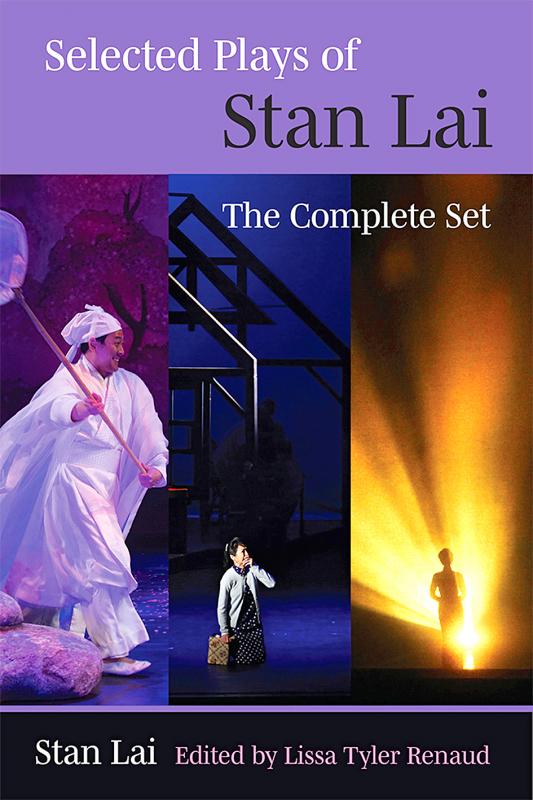

Lai is of course essentially a playwright and this three-volume selection from his plays opens with what is perhaps his best-known creation, Secret Love in Pearl Blossom Land (暗戀桃花源, 1986). It features two plays, a tragedy and a comedy, that are accidentally scheduled for rehearsal at the same time on the same stage.

Lai may not be a great opera fan but the device mirrors the one in Richard Strauss’s 1912 opera Ariadne on Naxos where the same situation occurs.

The play begins with a pair of lovers on Shanghai’s Bund in 1948. It soon becomes apparent that this is just a theatrical rehearsal, and the two actors start a conversation as actors rather than characters, and are then joined by the director.

But then the actors from the second play, In Pearl Blossom Land, based on a Chinese classic from the fifth century, arrive.

This is of course a brilliant theatrical device. In Richard Strauss’s opera the problem is solved by the two different operas being performed simultaneously. You’ll have to read his text to find out how Lai resolves it.

It has to be said that all the plays in these volumes are written in perfect colloquial English. Lai was born and educated in the US and is bilingual, equally at home in both Western and Chinese cultures. Secret Love was performed in English at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2015 as well as in Mandarin in China. There are thought to have been over 1,000 illicit productions of it in China over the years.

Menage a 13 features an estranged husband and wife who fall for each other again when they are in disguise. There’s an operatic precedent for this too — see the last act of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro.

The Island At the Other Shore (1989) and I, Me, She, Him (1998) both deal with cross-strait relationships, following the gradual opening up of visits between Taiwan and China in the late 1980s.

The prolific Lai has also translated major plays by Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Anton Chekhov and Carlo Goldoni, as well as creating the opening and closing ceremonies of the Deaflympics in Taipei in 2009.

Volume Two opens with Millennium Teahouse (千禧夜,我們說相聲) which, after its Taipei premier, became his first play to be performed in Beijing with its original Taiwanese cast.

The two massive plays that fill Volume Three are among Lai’s most mystical, reflecting his deep interest in Tibetan Buddhism. Both were originally conceived in locations sacred to Buddhists, A Dream Like a Dream (如夢之夢, 2000) in Bodhgaya, India, and Ago: A Journey through the Illusory World (2019) in the culturally Tibetan area of Qinghai. Both plays are immensely long, Dream seven and a half hours, Ago five and a half — each longer than any Wagner opera.

Lai, who created many of his plays through improvisation sessions with his actors, while remaining responsible for the initial concept and the final wording, is undoubtedly Taiwan’s premier dramatist. Born and educated in the US and with a PhD from Berkeley, California, he has lectured at both Berkeley and Stanford, as well as National Taiwan University.

These three volumes, edited by Lissa Tyler Arnaud, contain 12 of Lai’s plays out of a current total of 41. (Bernard Shaw wrote 51, though some are short one-acters).

The major masterpieces — such as Peach Blossom, Dream and Ago — are all included. In addition, essays by Lai on how he writes and how he translates are reprinted in each volume, together with introductions to the plays in each book by Raymond Zhou (雷蒙德周) and (volume three) Jao Qingmai.

One of the most distinctive, and interesting, features of Lai’s plays is that, although he’s a Taiwanese dramatist, his works have very frequently been staged, and to great acclaim, in China.

This is especially significant in light of the fact that Lai incorporates many progressive Western features — drama as ritual, for example — and plays that strive to push the boundaries of what theater can actually be. The name Peter Brook might be mentioned here as an influence. His Mahabharata (1985), which turned an Indian epic into a piece of theater, can be compared to Lai’s use of Buddhist texts and traditions in Dream and Ago.

But Brook’s most creative period was a generation ago, whereas Lai is opening the eyes and the minds in China and elsewhere in the present.

Dream Like a Dream and Ago embody these progressive tendencies, with their physical staging pushing the envelope, with at least part of the audience sitting on swivel chairs in the sunken center of a circular acting area, with the actors constantly walking in a clockwise direction round and round them.

Lai, who was born in 1954, is still only 67. Let’s hope that he has many more extraordinary theatrical experiences in store.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the