It wasn’t until 7am that Masha Gorenkova realized something serious was up. The first explosion had woken her at 4:30am, and several more had occurred in the interim; but like most of the neighbors in her Kyiv apartment block, she hadn’t twigged. Given the tone of inevitability from many quarters in the build up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, the revelation that Ukrainians were taken by surprise seems counterintuitive. Yet incredulity was widespread among those on the ground and relatives further afield. Few thought this would happen.

“I was shocked,” Gorenkova, a 25-year-old teacher, tells the Taipei Times. “Nobody had been really talking about this; everyone was just quietly going about their business.”

Schools and workplaces were, at this point, thought to be operating as normal and many people were beginning their daily routines. Based on uncertainty over the explosions and reports of heavy traffic across the city, Gorenkova decided to stay home with her 13-year-old sister. Soon, the unthinkable was confirmed.

Photo courtesy of Liza Bielova

“People were hoarding food at stores, leaving the city and evacuating offices and homes,” Gorenkova says. “It became really crazy really fast.”

Situated on the eastern fringes of Kyiv, Gorenkova’s apartment overlooks the E40 road to Zhytomyr, the next major city to the west and a major transportation hub. It was soon reported that the explosions and ongoing din came from 15 kilometers northwest at Antonov (or Hostomel) Airport, an international cargo hub that is also used by the transportation wing of the Ukrainian Air Force.

The airbase was one of the first sites to be attacked and has seen fierce fighting ever since. The destruction of the 314-ton Antonov An-225 Mriya, housed in one of the hangars, made headlines on Feb. 28. The plane was reportedly the world’s largest aircraft. More recently, the mayor of Hostomel was reportedly shot dead by Russian forces while distributing aid. As the noise intensified, Gorenkova — a devout Christian — and members of her church group gathered at a local home to pray and discuss what to do. A spontaneous decision to get out of Kyiv was made by the head of the congregation. The destination was Sytnyky, a village 50 kilometers southeast of Kyiv.

Photo courtesy of Liza Bielova

Some of the church members had family located in the village who were willing to take in as many people as possible. More than 40 people crammed into eight vans for the trip. The drivers took a circuitous route through the backroads to avoid major thoroughfares, which were by now considered hazardous.

CONTRASTING EXPERIENCES

Gorenkova was not yet thinking of herself as a refugee.

Photo courtesy of Masha Gorenkova

“Our pastor, Valery, just thought it was best to leave the city for a while and wait for this turbulent time to end,” she says. “We thought we’d be there just a day or two, then return to normal life in Kyiv.”

Weary and shaken, the group bedded down for the night with sleeping bags on the floors of their benefactors’ homes. The next morning, reality kicked in.

“We were told it wasn’t safe to return to Kyiv because the roads were too dangerous,” she says. “The Russian army was trying to surround the city.”

Photo courtesy of Masha Gorenkova

On the south side of Kyiv, Margo Martynenko has had a very different experience. The 27-year-old was less than two weeks back from a trip to the Seychelles when the invasion began.

“We are relatively lucky here — it’s quiet in my neighborhood,” she says. As a remote worker, she considers herself particularly fortunate. “For us, it’s the easiest.”

Not so for many of her friends and acquaintances around the country, particularly in Irpin, a city on Kyiv’s northwest border where ferocious fighting continues.

Graphic: James Baron

“My boyfriend’s two colleagues are from there, where the most horrific battles are happening,” Martynenko says. “Both had their homes bombed and are now homeless.”

IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

Like most of her compatriots, Martynenko expresses contempt for the invaders.

“Everyone hates the Russians,” she says. “They keep hitting civilian infrastructure and residential buildings. The damage is enormous and there are many children among the casualties.”

She is ambivalent about her feelings on returning from an Indian Ocean paradise to a war-torn homeland but remains upbeat about the leadership shown by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

“Those who did not support him before are now totally happy to have such a president,” she says. “Everyone thought he would flee the country, but he didn’t.”

Martynenko highlights a survey by the Institute of Cognitive Modeling, a nongovernmental organization that provides psychological support to Ukrainians in times of crisis. It shows strong backing for Zelenskyy and resolution in the face of the odds.

“The majority of people think we will win,” Martynenko says. “Most of them are ready to wait as long as necessary so that Ukraine wins on its terms.”

More than 750 kilometers southeast at the port city of Berdyansk, which juts onto the Sea of Azov, Liza Bielova tells a different story. With an absence of Ukrainian forces in Zaporizhzhia Province, where Berdyansk is located, since Russia established control in the neighboring Donbas region in 2014, Russian forces entered unopposed on Feb. 27.

UNWELCOME VISITORS

Like much of the city’s population, Bielova is an ethnic Russian. She spent large portions of her childhood in her ancestral homeland but hasn’t returned since 2008. Fond childhood memories have given way to fear, resentment and animosity.

“The first few days, I could not sleep at night. I was afraid that I’d miss a bomb,” she says. “Air raid sirens were sounding all the time, and my neighbors were running up and down to the shelter.”

For several days, she stood in lines at supermarkets, banks and drugstores, trying — like everyone else — to ensure she had the basic necessities. When the occupiers blocked Internet access for 24 hours, a feeling of hopelessness took hold.

“I wanted to cry all the time, because I could not imagine how to live this new life,” says Bielova. “I had a fear that one day I’d wake up and my country would not exist. At some point, the days all felt the same — each like a nightmare.”

Since the Donbas virtual occupation and the contemporaneous annexation of the Crimea, Moscow’s propaganda has inevitably focused on the supposed universal support it draws from its “compatriots.”

However, the response of many ethnic Russians has shattered the myth of benevolent invaders afforded a rapturous welcome.

THREATS AND HARASSMENT

Even those who seemed more likely to accept the occupation have balked at the affront of being bullied in their own backyard. Among them is Bielova’s father, an ex-soldier in the Soviet army, who was posted to Donetsk 30 years ago and chose to settle in Ukraine.

“We pray for this country. The Russians have occupied my city. This is our home.”

Since seizing control of Berdyansk, Russian forces have harassed the city’s officials. Last week, they cordoned off the building where Bielova lives and broke into the flat of a former police chief, removing unspecified possessions. Presciently, the former occupant had left well in advance.

“They were digging up dirt,” says Bielova. “I think he knew they were coming.”

Having been threatened with removal or arrest for refusing to cooperate with the invaders, the city’s mayor has relocated from his office to an undisclosed location. Meanwhile, citizens are routinely prevented from leaving their immediate environs and followed when they do so.

“When I go outside to walk the dog, the soldiers followed me closely,” Bielova says. “One guy who refused to lend a Russian soldier his phone to make a call home was shot dead the other night.”

TAKING TO THE STREETS

But the people remain uncowed. Since the initial anxiety, street protests have become a daily occurrence. Wherever the loathed “Z” symbol has been spotted, citizens have confronted the occupiers. “Go home while you are still alive” has become a popular refrain. As in many cities in the southeast, Russian soldiers fire shots into the air to disperse the crowds, but it’s no longer working.

The fear is things might escalate. In the neighboring province of Kherson, Russian forces have begun to crack down, arresting 400 protestors in the capital city on Wednesday. On the other side of Berdyansk, a humanitarian disaster is unfolding in Mariupol, where incessant Russian shelling is making a mockery of promises to respect a ceasefire over a green corridor out of the city.

“These are not men of their word,” Bielova says. “They say there is no goal to hurt civilians, but they are consciously shelling and bombing civilian targets, So of course there is fear that they could become more aggressive toward us. We live in fear every day.”

From the relative safety of Lviv province, where she and her sister have found refuge, Gorenkova has an eye on Kherson where her mother and grandmother live.

“She has trouble walking,” Gorenkova says of the elder matriarch. “But she, too, wants to join the protests.”

ON THE MOVE AGAIN

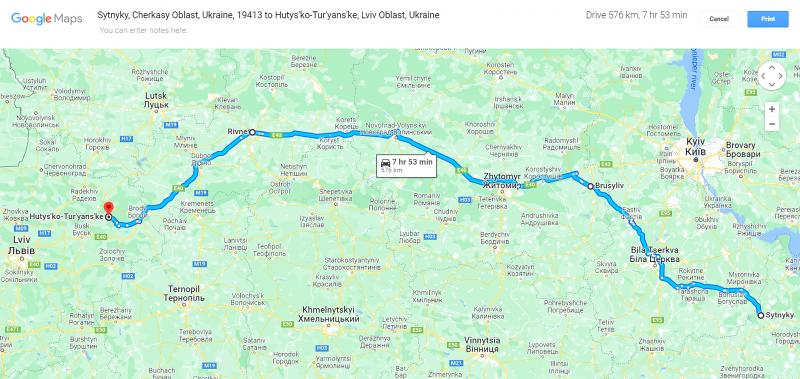

Having spent a week in Sytnyky where “the skies were red every night from explosions” and the conflict appeared to be getting perilously close, Gorenkova’s group was finally given clearance to head westward.

“There was a guy from the Territorial Defense Forces [TDF, the Ukrainian army’s reserve force] in the house, so he knew what was going on,” Gorenkova says. “On the third day, the Russians got close and there was serious fighting. This lasted for several days until the TDF beat them back and cleared the area.”

Yet, the group was still awaiting the arrival of humanitarian aid missionaries, who had been held up by the encroaching conflict. When the missionaries arrived on March 4, Gorenkova’s group followed them back to their base in Brusyliv, Zhytomyr region, several hours northeast. (It is a peculiar irony that the name of Russia’s great World War I general Alexander Brusilov derives from this town.)

“We had to go along a dirt track through a forest for 50 kilometers to get there,” Gorenkova says. “We stayed for two nights but the longer we were there, the closer the war sounded. At lunchtime on the second day, a burning fighter jet came down over the home we were staying in and crashed into a field nearby.”

Startled by the proximity of this event, the group wanted to move on, but didn’t.

“There was a curfew until 8am,” Gorenkova says. “If we’d tried to leave, we might have been shot by our own soldiers.”

HELPING HANDS

The minute the curfew expired on Monday, they were on the road again — this time to the neighboring province and town of Rivne. Having spent the night at a children’s camp facility, Gorenkova decided to separate from the group, after an acquaintance offered to accommodate the two sisters. With dozens of people arriving at the makeshift refugee camp, Gorenkova felt they would be an unnecessary drain on resources.

“We had somewhere to go, so it was better to make space for others,” she says.

In the remote, wooded hamlet of Hutysko-Turyanske, 85 kilometers northeast of Lviv, western Ukraine’s largest city, the sisters have just enjoyed their first sound sleep in two weeks.

“The whole time, we slept in our clothes, our backpacks packed, ready to leave any second or jump in the basement to hide. Now we’re finally back to something like normal life.” She is unsure if she will be able to return to Kyiv or what she will find if she does.

“If Irpin falls, my apartment is next,” she says.

Gorenkova hopes to assist other refugees or “help in any way I can” but, for the moment, feels duty-bound to care for her sister. Friends around the country have become unreachable, and there is constant anxiety about their well-being.

“I open Instagram, and people I know who were volunteering have been shot and killed,” she says. “Whenever the connection is good, we’re sending each other short messages. Just simple stuff: ‘I’m good, I’m alive, I’m safe.’”

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they