Feb. 28 to March 6

Tang Te-sheng (湯德生) stepped out of Taichung Railway Station on March 3, 1947 to see a group of civilians struggling against government troops. He and the other panicking passengers ran from the scene, but the soldiers followed and fired into the crowd.

The violence he witnessed was part of the aftermath of the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that started in Taipei three days earlier and was soon brutally suppressed. The fed-up people of Taichung decided to join the revolt on March 2, and fighting was still going on when Tang got off the train.

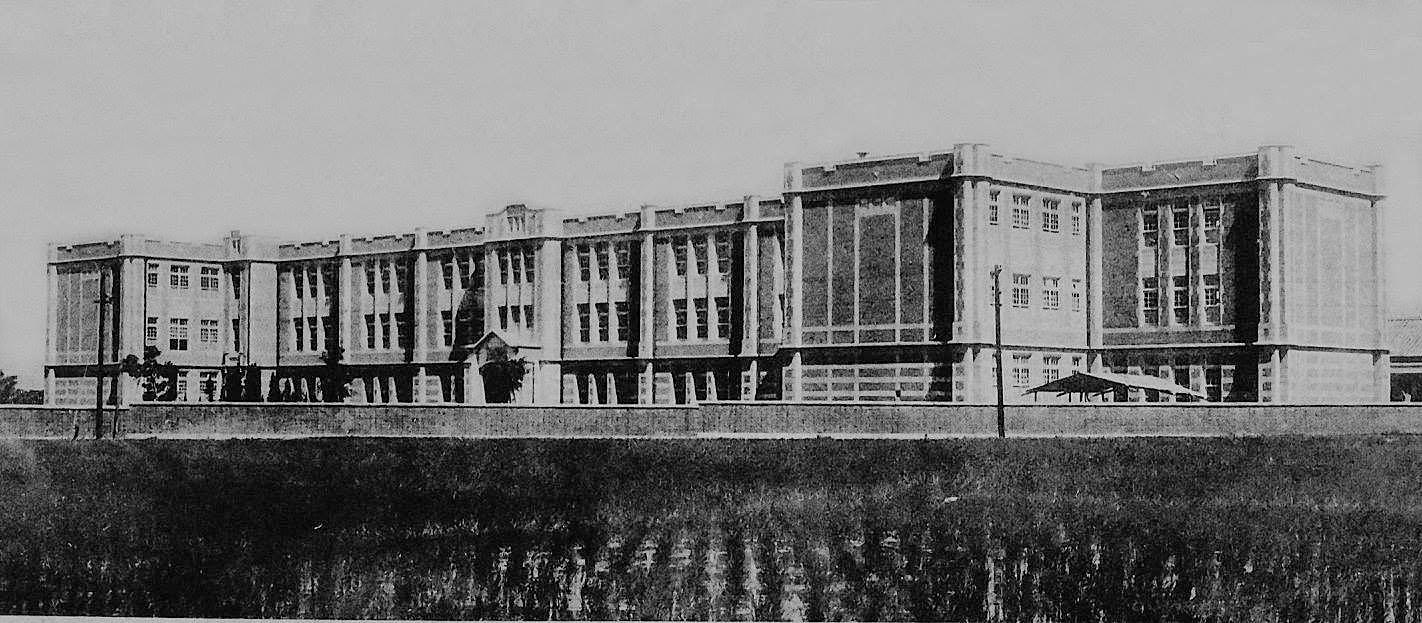

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tang survived, but he was outraged. Once he made it back to the campus of Taichung Normal School (today’s National Taichung University of Education), he joined the resistance alongside many of his peers.

Taichung Normal School played a notable part in the fight against the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — there was plenty of action in the area since the anti-government 27 Brigade (二七部隊) was based in the city. According to the 2018 book The Campus in a Storm (暴風雨下的中師), students formed at least two armed groups, one of which guarded the campus while the other joined the 27 Brigade and took part in their last stand on March 16.

Although he reportedly remained neutral, Principal Hung Yan-chiu (洪炎秋) didn’t stop the students and was fired after the events. Several staff members were put on the wanted list and, according to the book, about 10 percent of the students never returned to school. Many dropped out in fear of repercussions; others were arrested, killed in battle or forced to go into hiding.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TAICHUNG RISES UP

Tang was at home in Miaoli when the unrest began, and he had no idea about the events until he arrived in Taichung. The news had reached the city by March 1, and members of the local elite such as Yang Kui (楊逵) and Chung Yi-jen (鍾逸人) announced a public assembly the following day. Nearly 1,000 people — including Taichung Normal School students — arrived, and noted communist Hsieh Hsueh-hung (謝雪紅) was elected assembly chairwoman.

After the meeting, the crowd took to the streets in protest, taking over various government facilities and seizing weapons from a local police station. They then surrounded the home of county commissioner Liu Chun-chung (劉存忠) and clashed with his guards. After three protesters were shot, the angry crowd started collecting gasoline to burn down the mansion. Hsieh rushed to the scene and managed to stop them, although there were already casualties on both sides.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

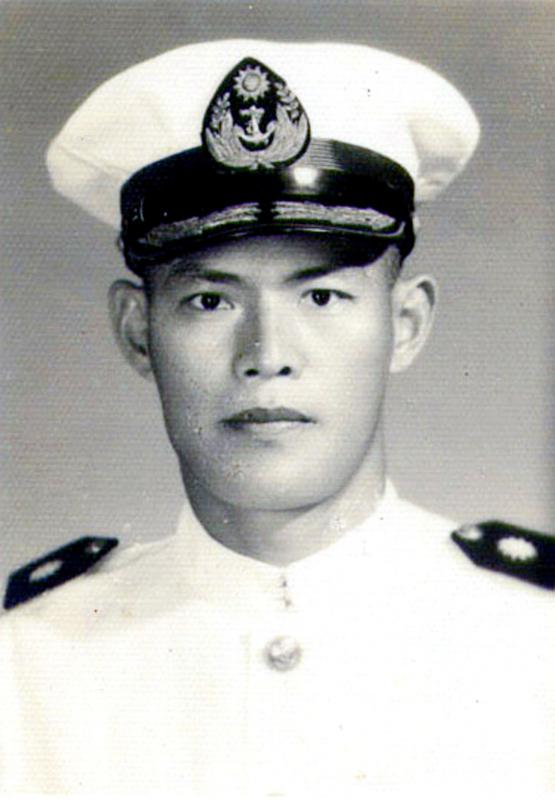

Taichung Normal School’s physical education instructor Wu Chen-wu (吳振武) was one of the few staff with combat experience, serving as a lieutenant in the Japanese Navy during World War II. Local leaders such as Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) hoped that Wu would help lead part of the resistance since they distrusted Hsieh due to her communist leanings.

He was reluctant at first, but on March 2, nearly 200 of his former comrades arrived at the school and asked him to lead them. He organized them into a self-defense force whose job was to guard the campus and protect the China-born teachers and their families from being harmed.

Sources vary on whether this group included students, but it seems that Wu also led the self-formed student groups such as the one Tang joined.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“They didn’t have any military knowledge,” 27 Brigade member Huang Chin-tao (黃金島) recalls in a 2017 News Lens article. “They were loosely organized and didn’t even know how to shoot a gun.”

The resistance force grew throughout the day as militias from the vicinity congregated in Taichung. Hsieh set up combat headquarters at Taichung People’s Hall and announced the formation of a “people’s government.”

STUDENTS IN ACTION

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The battle Tang saw in the morning culminated in an afternoon showdown at the former Taichung Enlightenment Hall (台中教化會館), the government troops’ temporary base in the city. After a six-hour standoff, the troops surrendered and the rebels took the building and bolstered their firepower. Tang’s crew was in charge of supplies, and he recalls delivering several boxes of grenades to the scene. He notes that most of the combatants he saw were indigenous people from Puli (埔里).

After the battle, Tang’s group was tasked with taking over the surrendered KMT 8th Brigade’s facilities. At one point, they were instructed to reinforce the resistance in Chiayi — but the request was called off for reasons unknown. “It would have been disastrous for us if we had gone,” Tang says.

Instead, they helped take over the nearby Air Force base, whose commanding officer had agreed to peacefully surrender. The troops there did not move or talk when he entered the barracks.

By this time, Wu was out of action due to a mysterious gunshot wound, and school alumnus Lu Huan-chang (呂煥章) returned to campus and led a group of students fighters into Hsieh’s newly christened 27 Brigade. Things soon took a grim turn, however, as KMT reinforcements from China landed in Keelung on March 8.

Tang’s group was stationed in Caotun (草屯) when they heard the news. Since they were barely armed, they decided to disband and flee. Tang and three comrades hid at an indigenous classmate’s house in Wushe (霧社) for the night. Wu also disbanded his group as he didn’t want more young people to die, but the 27 Brigade prepared to take on the government forces.

“I didn’t run into Lu the whole way, otherwise I would definitely have joined him and headed to the fight in Puli,” Wu says. “Perhaps this is why I’m still alive today.”

Instead, with just one rifle between the four of them and two grenades each, they made the treacherous walk back to Miaoli, begging for food or stealing fruit to survive. They almost got caught once after locals reported them, but after about a week, Tang made it back to the safety of his family home.

SURVIVOR

Tang returned to school on March 29 as if nothing happened. Although the school became involved in several future White Terror incidents, Tang believes that there were no serious immediate repercussions because they protected the mainlander staff. Tang even participated in the patriotic Youth Day parade that day, and along the way he ran into one of the commanders at the military airport.

“He even said hello to me. Fortunately, he didn’t report me,” Tang says.

When Tang was interviewed for the book, he revealed a secret he had been hiding for 70 years. By 1948 or 1949, he and a few friends saw little hope for Taiwanese under the KMT and decided to head to China and join the communists. However, flight prices to Hong Kong surged right before their departure, thwarting their plans.

One of these friends, Liu Tien-fu (劉天福), was later arrested and executed. Once again, however, Tang evaded death.

“Liu never told the authorities about our plan, even under torture,” he says. “Otherwise I would have definitely been shot too.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand