The theory of general relativity holds that a massive body like Earth curves space-time, causing time to slow as you approach the object — so a person on top of a mountain ages a tiny bit faster than someone at sea level.

US scientists have now confirmed the theory at the smallest scale ever, demonstrating that clocks tick at different rates when separated by fractions of a millimeter.

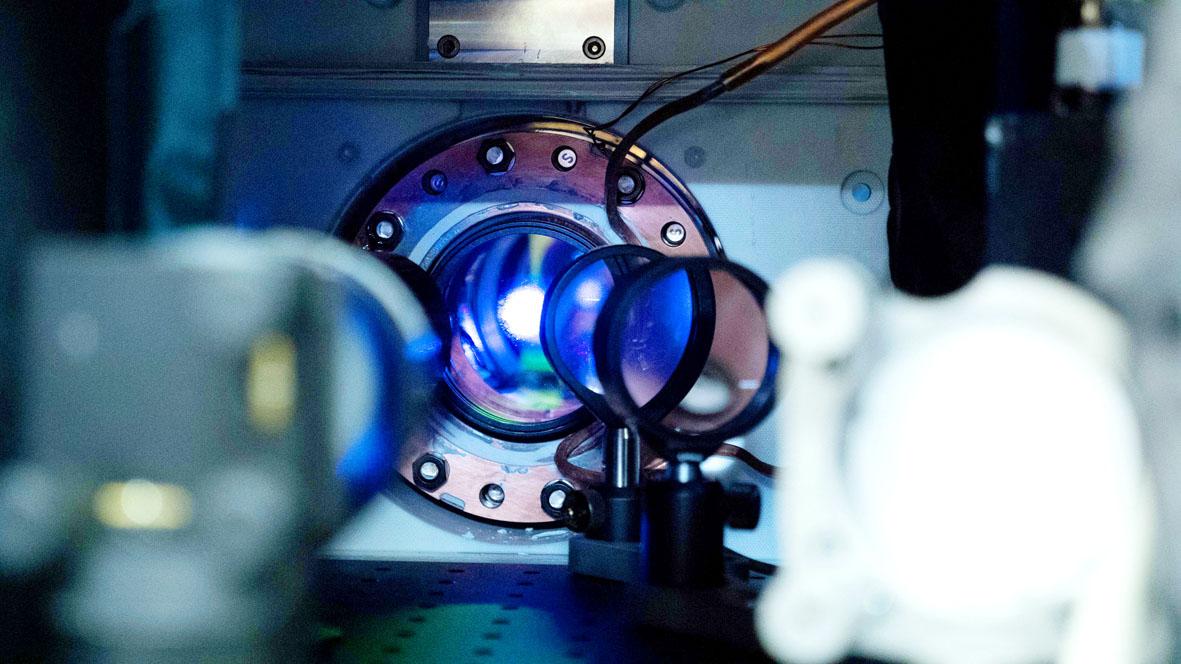

Jun Ye, of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder, said their new clock was “by far” the most precise ever built — and could pave the way for new discoveries in quantum mechanics, the rulebook for the subatomic world.

Photo: AFP

Ye and colleagues published their findings Wednesday in the prestigious journal Nature, describing the engineering advances that enabled them to build a device 50 times more precise than today’s best atomic clocks.

It wasn’t until the invention of atomic clocks — which keep time by detecting the transition between two energy states inside an atom exposed to a particular frequency — that scientists could prove Albert Einstein’s 1915 theory.

Early experiments included the Gravity Probe A of 1976, which involved a spacecraft 10,000 kilometers above Earth’s surface and showed that an onboard clock was faster than an equivalent on Earth by one second every 73 years.

Since then, clocks have become more and more precise, and thus better able to detect the effects of relativity.

In 2010, NIST scientists observed time moving at different rates when their clock was moved 33 centimeters higher.

THEORY OF EVERYTHING

Ye’s key breakthrough was working with webs of light, known as optical lattices, to trap atoms in orderly arrangements. This is to stop the atoms from falling due to gravity or otherwise moving, resulting in a loss of accuracy.

Inside Ye’s new clock are 100,000 strontium atoms, layered on top of each other like a stack of pancakes, in total about a millimeter high.

The clock is so precise that when the scientists divided the stack into two, they could detect differences in time in the top and bottom halves.

At this level of accuracy, clocks essentially act as sensors.

“Space and time are connected,” said Ye. “And with time measurement so precise, you can actually see how space is changing in real time — Earth is a lively, living body.”

Such clocks spread out over a volcanically-active region could tell geologists the difference between solid rock and lava, helping predict eruptions. Or, for example, study how global warming is causing glaciers to melt and oceans to rise.

What excites Ye most, however, is how future clocks could usher in a completely new realm of physics. The current clock can detect time differences across 200 microns — but if that was brought down to 20 microns, it could start to probe the quantum world, helping bridge disparities in theory.

While relativity beautifully explains how large objects like planets and galaxies behave, it is famously incompatible with quantum mechanics, which deals with the very small.

According to quantum theory, every particle is also a wave — and can occupy multiple places at the same time, something known as superposition. But it’s not clear how an object in two places at once would distort space-time, per Einstein’s theory.

The intersection of the two fields therefore would bring physics a step closer to a unifying “theory of everything” that explains all physical phenomena of the cosmos.

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent