Scientists have uncovered the world’s oldest social network, a web of connections that flourished 50,000 years ago and stretched for thousands of miles across Africa.

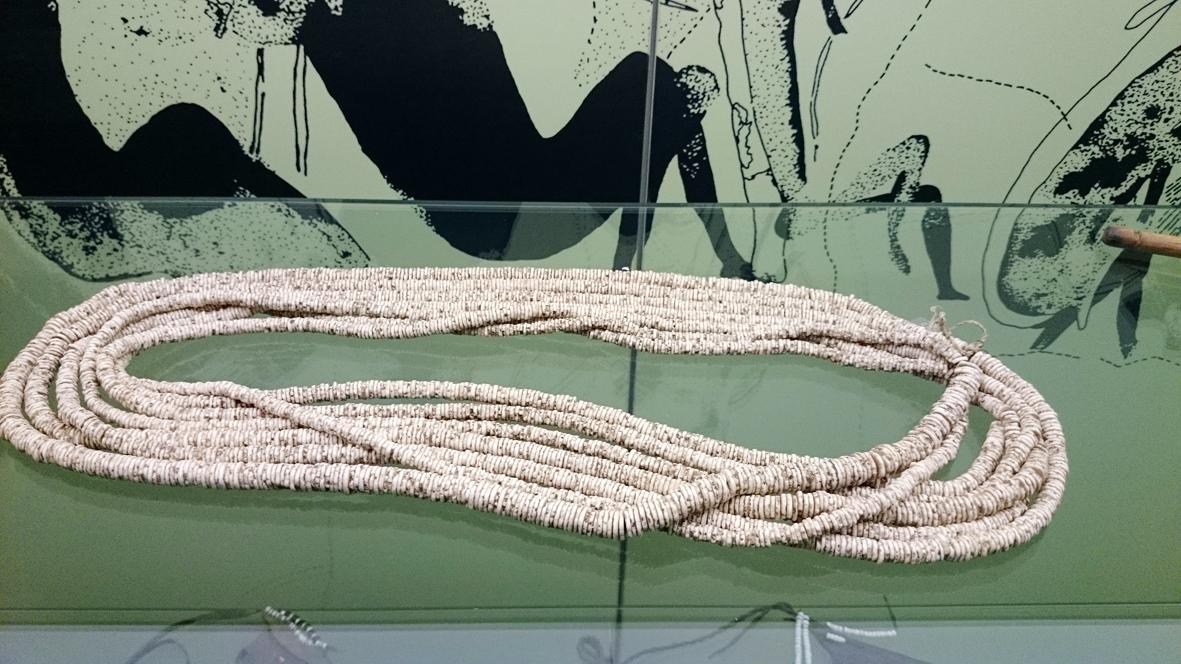

But unlike its modern electronic equivalent, this ancient web of social bonds used a far more prosaic medium. It relied on the sharing and trading of beads made of ostrich eggshells — one of humanity’s oldest forms of personal adornment.

The research by scientists in Germany involved the study of more than 1,500 of these beads, which were dug up at more than 30 sites across southern and east Africa. Careful analysis suggests that people who made the beads — which are still manufactured and worn by hunter-gatherers in Africa today — were exchanging them over vast distances, helping to share symbolic messages and to strengthen alliances.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“It’s like following a trail of breadcrumbs,” said the study’s lead author, Jennifer Miller, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in the city of Jena. “The beads are clues, scattered across time and space, just waiting to be noticed.”

The study, published in Nature last week, compared beads found at 31 sites in southern and eastern Africa, spanning more than 1,800 miles. By comparing the outside diameter of a shell, the diameter of the holes inside them, and the thickness of the walls of the eggshell, the scientists learned that about 50,000 years ago people in eastern and southern Africa started to make nearly identical beads out of ostrich eggs.

Yet these groups and communities were separated by vast distances, which suggests the existence of a long-distance social network that stretched over thousands of miles, connecting people in far-flung regions. “The result is surprising, but the pattern is clear,” said the study’s other author, Yiming Wang, who is also based at the Max Planck.

Ostrich eggshell beads are some of the oldest forms of self-decoration found in the archaeological record, although they were not the first to be adopted by Homo sapiens. Scientists believe men and women started daubing themselves with the reddish pigment ocher about 200,000 years ago, before starting to wear beads 75,000 years ago.

However, the ornament industry really took off about 50,000 years ago in Africa, with the manufacture of the first ostrich eggshell beads — the earliest standardized form of jewelery known to archeology. This was the world’s first “bling” and its use represents one of humanity’s longest-running cultural traditions, involving the expression of identity and relationships. As Miller put it: “These tiny beads have the power to reveal big stories about our past.”

Or as archaeologist Michelle Langley of Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, has said: “Bling is valuable: it tells us something about the person who wore it. More bling in the archaeological record indicates more interactions. Traded bling tells us who was talking to whom.”

The crucial point about ostrich eggshell jewelery is, instead of relying on an item’s natural size or shape, humans began to shape the shells directly and create opportunities for variations in style to develop. The resulting patterns gave the researchers a route through which they could trace cultural connections, though it is unclear if the ostrich eggshell beads studied by Miller and Wang were traded between groups or if it was the knowledge of how to manufacture them that was exchanged. Most evidence points to the latter.

The world’s first social network did not last. About 33,000 years ago, the pattern of bead-wearing abruptly changed: they disappeared from southern Africa while continuing in east Africa. Miller and Wang suggest climatic changes lay behind this, bringing an end to the planet’s oldest social network — albeit after 17,000 years.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that