It’s as if the outside world conspired to rob Yanshuei (鹽水) of its importance and prosperity.

As waterways filled with silt, access to the ocean — which had made it possible for this little town, several kilometers from the sea in the northern part of Tainan, to become a major entrepot — was lost. The north-south railway, a key driver of economic development during the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, never arrived. Then, in the 1970s, the sugar industry went into terminal decline.

Like Taiwan’s other old settlements, Yanshuei used to be a walled town. The defensive barrier is long gone, but there’s a reminder of the gates through which humans, horses and bullock carts entered and left in the form of street names.

Photo: Steven Crook

HISTORIC STREETS

The Martial Temple (武廟), a co-organizer of the annual Beehive Fireworks Festival (鹽水蜂炮), is at the intersection of Beimen Road (北門路, North Gate Road) and Wumiao Road (武廟路). The festival, which celebrates the end of a cholera outbreak that ravaged the town more than 130 years ago, gets its name from the fireworks holders that are positioned around the town. When the fuse on one is lit, thousands of bottle rockets screech out, much like angry bees.

Photo: Steven Crook

Yanshuei’s most interesting place of worship stands at 19 Simen Road (西門路, West Gate Road). On the outside, the Holy Trinity Catholic Church and Monastery of St Clare (鹽水天主堂) is unexceptional. Its interior, however, is captivating.

A huge depiction of the “last supper” is one of the highlights. In it, Christ and each of his apostles have Asian facial features and wear traditional Chinese garb. There are chopsticks and plates of steamed buns on the table.

Part of Nanmen Road (南門路, South Gate Road) runs parallel with Ciaonan Street (橋南街, South of the Bridge Street), one of the oldest thoroughfares in south Taiwan.

Photo: Steven Crook

Beginning my most recent walking tour of the town near Ciaonan Street, I was pleased to see that urban beautification efforts have turned what used to be Yanshuei’s docklands into an attractive green corridor. Now called Yuejingang Waterside Park (月津港親水公園), it’s certainly a pleasant spot for a picnic. But for anyone wishing to see what remains of the town’s history, it’s a very minor attraction.

On Ciaonan Street, there are several single-story houses made mainly of wood, and a few of them could be 200 years old. An unnumbered lane gives access to the backs of the buildings on the east side of the street; walking down it, I wasn’t surprised to see that some of the more traditional structures are in a very sorry state indeed.

Circling around onto the street itself, I tried to peek into No. 25. Years ago, it was the site of a small museum displaying household antiques. It looks like it could survive a few more decades, if the owners allow that. The plots on either side have been cleared.

Photo: Steven Crook

Ciaonan Street’s most famous resident is a sixth-generation blacksmith who plies his trade the old-fashioned way. At Chuan Li Blacksmith Shop (泉利鐵店) at No. 8, where his father and grandfather used to make farmers’ tools, he forges decorative items for tourists.

FAMOUS NOODLES

Lunchtime was approaching, so I did what I usually do in Yanshuei: Head for the covered food court at the intersection of Kangle Road (康樂路) and Jhongshan Road (中山路), and sit down at A-San’s Egg Noodles (阿三意麵) for a portion of the unpretentious dish that gives this decades-old eatery its name.

Like other noodle dishes in Taiwan, Yanshuei Egg Noodles (鹽水意麵) is flavored with a meat sauce assembled from small chunks of pork, a little soy sauce, some garlic and chives, and bean sprouts. The noodles are thin and flat.

A-San’s (open from 7am to 5:30pm every day except Thursday) offers both dry and soupy versions of its noodle dishes. Various side dishes are available; nothing costs more than NT$50.

While eating, I couldn’t help but notice that the food court was mostly unoccupied. Has COVID-19 caused several vendors to go out of business?

There’s a restored movie theater a stone’s throw south of the food court. Yongcheng Theater (永成戲院) was built during the Japanese period. It served as a rice mill until late 1945, when it was repurposed into a place of entertainment.

The theater was closed at the time of my visit. If you want to see the interior of this elegant landmark, visit between 1:30pm and 5:30pm on Wednesday, Thursday or Friday, or between 9:30am and 5:30pm on weekends.

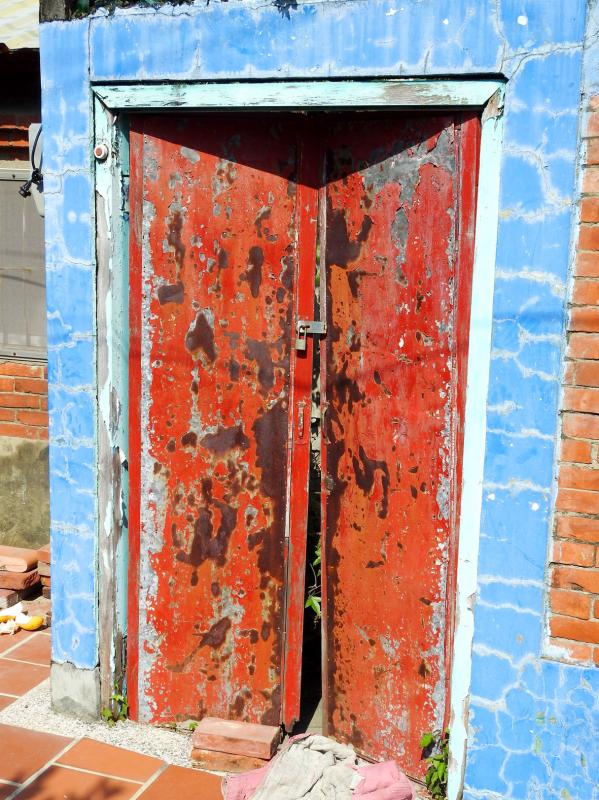

Every time I’m in Yanshuei, I try to get lost in backstreets, in the hope I’ll stumble across some characterful vernacular architecture.

Sometimes, it’s just a doorway. Other times, it’s a complete house. On this occasion, it was what appeared to be a ground-up reconstruction of a traditional home on Lane 4, Minsheng Street (民生街4巷). I saw no indication that this was a government project. It’s uplifting to know there are people willing to spend their own money to retain Yanshuei’s character.

DRIFTING WESTWARD

I was also pleased to see that the Octagonal Building (八角樓) is still in excellent condition.

This landmark was constructed circa 1847 as part of a luxurious mansion for sugar magnate Yeh Kai-hung (葉開鴻). The rest of the complex is long gone, but the two-story pavilion continues to grace Jhongshan Road, between the post office and the intersection with Jhongjheng Road (中正路).

These days, because of the pandemic, visitors can only gaze at the exterior from the street. In the past, the ground floor was usually open. One time, the family who owns the building showed me around both the lower and mainly-timber upper part — and confirmed that, during the Beehive Fireworks Festival, there’s always someone at the ready with a bucket of water and a fire extinguisher, in case a smoldering bottle rocket gets lodged in the woodwork.

Continuing my westward drift, I ended up across the road from the town’s junior high school at Yanshuei Railway Station. Hold on: At the start of this article, didn’t I say that the railway never came through the town?

I did say that, and it didn’t. The station here was part of the Taiwan Sugar Corporation (台糖, TSC) rail network. Built to haul cane to sugar factories, between 1945 and 1982 the narrow-gauge system also ferried passengers between small towns and points on the north-south line.

I’d been to the station before, but had no recollection of the adjacent warehouses. These buildings lost their roofs long ago, and have been colonized by banyan trees. If you do come here, be sure to bring your camera: They’re quite a sight.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of