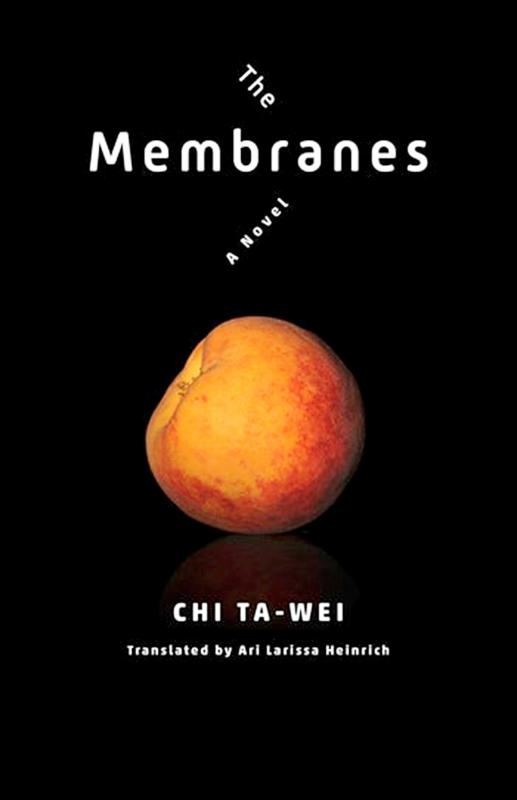

People talk about original novels, but Chi Ta-wei’s (紀大偉) The Membranes (膜) is more than original. It’s extraordinary.

Momo, the protagonist, lives under the sea, for a start. The year is 2200 and she’s 30 years old She was born, if that’s the right word, from inside a peach, and she works as a sort of masseur specializing in attaching membranes to her customers, so that they are completely covered by a new skin, independent of their original one. It’s called “dermo-maintenance.”

She considers having intimate relations with some of her customers but largely refrains. It’s only after several chapters that you realize something is odd. There aren’t any male characters, at least not yet.

Chi is 49 years old and he works as an assistant professor of Taiwanese literature at the National Chengchi University in Taipei. This novel was published in Chinese in 1995 when the author was 21. The present English translation, by Ari Larissa Heinrich of the Australian Centre on China in the World, Australian National University, appeared last year.

So — a Chinese-language, lesbian, “cli-fi” novel. Daniel Bloom, an American journalist in Taiwan, has been advocating the use of the term for futuristic novels based on climate change since I don’t know when, and here’s an obvious candidate. Congratulations Danny! Your day has come.

ALTERED WORLD

By the middle of the 21st century, 99 percent of humanity has moved to the sea bed. Only immovable monuments, such as “the February 28th Memorial plaques ubiquitous on the island of Taiwan,” remain in the unrelenting sun from which humanity is no longer protected by the ozone layer. Only one percent of people remain ashore, like prisoners. With sunlight like that, “who needed the electric chair?” Only black skin provides some protection, and religions such as Christianity have become restricted to blacks only.

Cyborgs, half human and half robot, can withstand more sunlight and so do most of the surface work such as maintaining solar panels. Meanwhile, underwater the old nations rule over territories roughly equivalent to their former extent, with great corporations such as Mitsubishi and Toyota ruling over the rest. A New Taiwan has become the financial center of a one underwater region, and Taipei has become “T City,” linked to the underwater living capsules by a “seaway corridor.”

Once Chi has established this global warming dystopia he is compelled to embark on some sort of plot. It’s hard not to feel he was reluctant to do this as there are long digressions before the story really gets going, such as one on the use of canaries to detect the presence of sarin gas in the 1995 Tokyo underground attacks, another on Momo’s three years in hospital starting at the age of seven, and cultural references ranging from Almodovar and Chanel to Shakespeare and the Mahabharata.

Even after the tale returns to Momo at 30, we get a long description of how the “M skin” she applies onto her clients has the secret power of conveying the client’s recent experiences directly into Momo’s own body where they are automatically digitized and catalogued.

Things then happen thick and fast. Momo buys a scanner that allows her to see into her mother’s bedroom and discover she has a female lover of Indian ethnicity. And then she herself goes to a park before the sun is strong and has sex of a kind with a basically female cyborg.

Momo goes back to the park the next day to find her cyborg lover. She’s there, but tells her that she’s due to have surgery later that day during which large parts of her body will be removed and transplanted into the body of her owner, a normal human being. This is the purpose of cyborgs, she explains — to act as sources for body-part replacements for those who have paid for their creation and upbringing. Sometimes entire bodies would be replaced, with only the brain of the original human remaining.

MYSTERY TAKES OVER

The sense of a mystery now takes over. Momo’s mother had kept away from her daughter since she was 10, though her stellar career with MacroHard (which had taken over from Microsoft) was clear to her offspring. But on Momo’s 30th birthday she suddenly reappears.

She’s carrying a laptop and Momo immediately wants to find out what it contains. She administers a spiked drink then discovers the password, hidden between the layers of skin of one hand. But Momo is astonished at what she then discovers — that the computer contains details of her own life that her mother couldn’t possibly have had any way of knowing.

A military dimension now enters the story. Highly specialized cyborgs, it turns out, are being developed in which the highest levels of military software are incorporated at birth. Momo doesn’t know this, but becomes involved nonetheless. And of course, with this level of interchange of body parts, who’s human and who’s cyborg is never far from the surface.

Heinrich adds a lengthy afterword in which he considers issues such as surveillance and implant technologies, the explorative world of post-1989 Taiwanese literature, sexual ambiguities of various kinds in that literature, the science fiction of US author Philip K. Dick, and so on. It transpires that The Membranes has been translated into English before, by someone who also wrote a PhD thesis on Chi’s work. This new translation from Columbia University Press, however, seems to be the first to appear in the mainstream media.

This book veers between a pathological interest in bodies and surgery, intensive cultural backstories, and inventive speculation about the future and climate change. It’s a future in which no-one can be sure who’s a cyborg and who’s not, in which no-one is definitely gay or straight, or indeed sure whether they are themselves male or female.

Short though it is, The Membranes stands at a major historical cross-roads in Taiwanese imagination and Taiwanese literature. As such it should be closely scrutinized at the very least.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has