Lin Yu-ju (林于如) pushed her mother down the stairs of her own home, causing head trauma that led to her death.

She poisoned her mother-in-law, first at home, later administering a second deadly dose in hospital via IV drip.

She killed her husband, too, the same way she dispatched her mother-in-law, though this time it took more than one attempt.

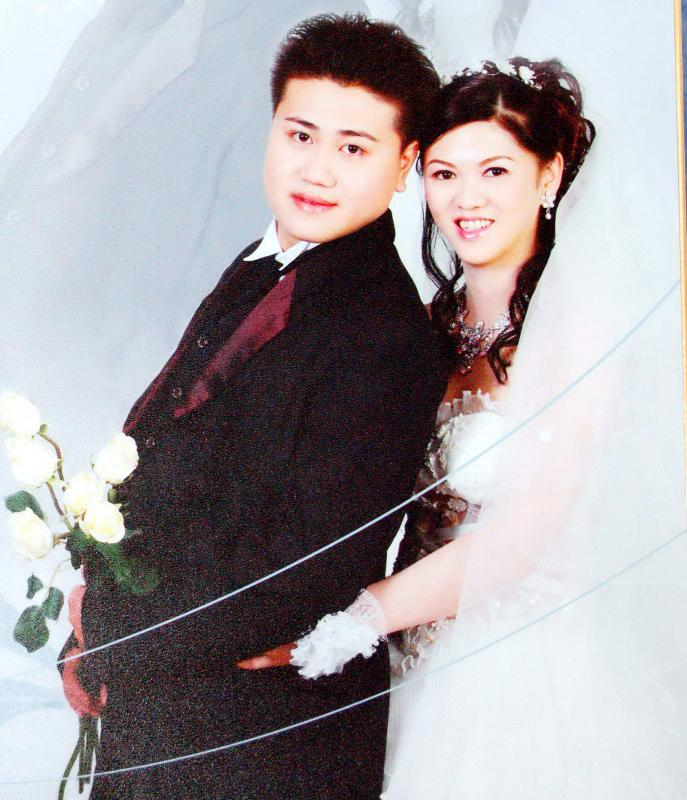

Photo: Tung Chen-kuo, Taipei Times

That Lin Yu-ju murdered three people is not in dispute.

The fact that two of Lin’s convictions were based largely on confession? That she had long suffered physical abuse at the hands of her husband, with whom she had also accumulated massive gambling debts? That the beatings she endured likely contributed to an addiction to painkillers, sleeping pills and anti-anxiety medications? That she has, according to medical reports, both bipolar disorder and mild intellectual disability?

According to trial records, all that mattered was that she killed, then she killed again and she killed a third time — three lives, people close to her, snuffed out in a matter of months. What is important is the who, what, where and when. “Why,” as it pertains to background, is immaterial.

So, according to the highest levels of Taiwan’s criminal court, Lin deserves to die.

Lin, 40, was born in Tainan in 1981. She and her sister, who still lives in Tainan, were close as kids. Theirs was a good family, according to a court-ordered background report — a normal family, by Lin’s own account. But after their father died due to causes unknown, when the girls were still young, the family fell on hard times.

After Lin graduated from vocational school, she and her sister went to work in a cabaret club, where men pay for the company of hostesses who sit and drink with them, sing karaoke and sometimes offer other, more intimate, services. This is where Lin met her future husband, Liu Yu-hang (劉宇航).

While Lin and Liu were dating, Lin became pregnant by him at least twice. Both times, the pregnancies were terminated. The Lius were a prominent Tainan family, famed for their tofu business. A child born out of wedlock would have brought shame to the Liu name.

When Lin got pregnant for a third time, however, she was told she could either have the baby or risk never being able to have children again. This time, she chose to have the child, and agreed to marry Liu.

Lin moved in with her husband’s family in Puli, Nantou County. After the baby was born, the beatings began. Or, more likely, the beatings continued. For years, Lin felt her husband’s hand. While enduring this abuse, she worked both in the home and without, running the Liu family’s tofu manufacturing and wholesaling business.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE, GAMBLING, DRUG ADDICTION

Liu, Lin’s defense team said in a report, backed up by a family doctor’s statements that would be rejected by the court, was perpetuating the cycle of abuse inherited from his father. Liu’s father beat his wife, and so Liu himself beat his, unable to put an end to the violence. The statements were thrown out during trial due to a lack of police records from the time of the alleged beatings. Lin, it seems, never filed charges against her husband. According to Wu Chia-chen (吳佳臻), deputy director of the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty, women’s reluctance to file domestic violence charges is commonplace, especially in traditional families, wherein the wife lives with the husband’s family.

The same family doctor who gave statements as to Lin’s injuries, inflicted by her husband, said that she and her mother-in-law visited the clinic together, where they would receive treatment for their cuts and bruises, and where Lin would receive medications. Somewhere along the way, Lin became addicted to those medications. More than once, Lin attempted to take her own life.

At some point, according to local reports and interviews with the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty, Lin also became addicted to gambling. She, along with her husband and members of his family, placed bets in the tens of thousands of New Taiwan dollars on the underground “Mark Six” lottery — a game of chance, run by gangsters. There is no indication that Lin or anyone else in the family ever won any significant amount of money. Still, time after time, they put their money down.

As gambling debts rose, so did the tension, both within Lin’s new family and her own. In late September of 2008, Lin took out life insurance policies on her mother and mother-in-law. On Nov. 10, she went back to Tainan to visit her mother. Early that afternoon, Lin would later confess, she and her mother began to argue about her gambling debts.

THE DEATHS

The quarrel escalated, turning physical. Lin pushed her mother down a stairwell, her body later found by her boyfriend’s son. At the time, police did not suspect foul play. Barely more than a week after her mother’s passing, Lin claimed her mother’s life insurance policy. On Christmas Day, 2008, a payout to Lin was made in the amount of approximately NT$5 million (US$165,000).

Five months later, in late May, 2009, Lin struck again. According to hospital records in Puli, Lin’s mother-in-law, Cheng Hui-sheng (鄭惠升), was taken to the emergency ward not long after midnight, exhibiting signs of illness. Lin later confessed that she had poisoned Cheng’s food at home. Cheng was treated and sent home, only to return the next day, showing similar symptoms. This time, Cheng had to stay overnight.

Lin and Liu took shifts, watching over Cheng. At around 4am, the day after Cheng was admitted, Lin said later under interrogation that she tampered with Cheng’s IV, adding a mix of crushed sleeping pills and anti-anxiety medications. It was a confession made, her defense maintains, because police threatened to implicate Lin’s sister in the killing if Lin herself did not make a full admission. Lin also said later that it was her husband who administered the fatal dose of medication to his mother, a technique she would learn and later imitate.

After slipping the poison into her mother-in-law’s IV drip, Lin waited two hours for the cocktail to take effect. At six in the morning, an hour after sunrise, she pressed the emergency call button. Doctors rushed to Cheng’s bedside to attempt to resuscitate her, but she was already gone. No autopsy was ever carried out on Cheng’s body.

Just a month later, in late June of 2009, Liu himself was taken to hospital, tended to by his wife. It was early in the morning, just past the midnight hour. As Liu lay prone in bed, Lin later confessed, again under threat of having her sister dragged into the case, she added deadly chemicals to his IV drip.

Just before 3am, Lin left the room for a while. While she was gone, a nurse, making her nightly rounds, came to Liu’s bedside. She noticed a discoloration in Liu’s IV bag, and hooked him up to another.

Two hours later, Lin was caught by hospital staff as she again administered a foreign substance into Liu’s IV. Staff stopped her, but if the police were alerted, there is no record. Liu survived, and was sent home.

Three weeks later, Liu was back in hospital. After a couple of days in a shared room, Lin arranged for him to be transferred to a private suite. Alone with her husband, Lin repeated the process, poisoning his IV drip. Liu fell weak, his body gradually giving out against the chemicals coursing through his veins. In the end, it took three days for him to die.

CONFESSION, TRIAL, DEATH SENTENCE

Lin then went on yet another Mark Six spree, placing bets in the five figures. Police became aware of the life insurance policies taken out by Lin on her husband and mother-in-law. A search warrant was obtained for Lin’s house, where the police said they found substances they believe were similar to those which they think (in the absence of an autopsy) were used in the killings of Liu and his mother. Lin was taken into custody, where she confessed under interrogation.

During the court trial, begun in early 2010, and the subsequent appeals process, the main evidence presented by the prosecution were Lin’s confessions, which she later retracted. In spite of the retraction, with the public baying for blood, Lin was sentenced to death.

Today, Lin waits on death row in Taichung Women’s Prison, occupying a single cell where her main mode of passing the time is writing letters to her sister, the advocates who work on her last-ditch appeal and a local journalist she corresponds with.

Her letters are stream of consciousness, thoughts careening back and forth from one topic to the next, like she can’t pin them down. This is likely due in part to another factor of her case that was largely ignored. Lin, according to records at the Tsaotun Psychiatric Center in Nantou County, where she was evaluated, has an IQ of 57, placing her at the low end of “mildly impaired or delayed.”

Those who interact with Lin in person say that when you speak to her, you would never suspect there is anything wrong, mentally speaking. But her evaluators say that it is in her decision-making processes that the impairment manifests — in the type of logic many of us take for granted when we face times of stress or hardship.

Lin, according to testing, lacks that decision-making capability. Chuang Chen-fen (張娟芬), Chairperson of the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty, says in a report that Lin and those like her tend to believe that if they repeat certain activities enough times, the desired result will come to pass, no matter how unlikely it might seem to an outside observer.

It is possible, says Chuang, Lin believed that as long as she kept playing, she would eventually win. To win, she needed to play. To play, she needed money. And it wasn’t just her, says Chuang. More than likely, the entire family was desperate for money, including Lin’s husband and her mother-in-law. They all had debts. They all felt the need to square them, to rise above them. But how far were they willing to go to see themselves free of the continual, crushing cycle?

In Lin’s trial, this bit of background information regarding her mental state was dismissed. She graduated from vocational school, said prosecutors. She ran her own business. She knew how to gamble. This was proof of intelligence, understanding of actions and consequences. The presiding judges were inclined to agree.

Today, Lin’s only hope of being saved from the firing squad is an appeal to the Council of Grand Justices on grounds of the constitutionality of the death penalty itself. That, or a presidential pardon. There are no limits to constitutionality appeals, but neither are there any demands for the council to take up a case. They can simply decline. Every Friday, rejections of constitutional appeals appear on the council Web site. Sometimes, no news is good news.

Perhaps working in Lin’s favor is the fact that the number of executions carried out by the Ministry of Justice has declined markedly in recent years, just three inmates killed by the state since 2016, where the year prior, six were put to death alone. Sentences of death, too, have tailed off, an average of one person condemned to die each year in the past five.

Currently, there are 38 inmates on death row in Taiwan — 37 men, and Lin, the lone woman. Over 10 years she has spent waiting, wondering if today is the day her order of execution will be signed, after which the sentence must be carried out within three days.

Regardless of the crimes she has committed, the question remains, the answer looming in the unknown:

Does Lin Yu-ju deserve to die?

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled