Jan. 10 to Jan. 16

Vowing to blow up a 2,000-tonne ship and paralyze Kaohsiung Harbor, fed-up residents of Hongmaogang Village (紅毛港) took action in the afternoon of Jan. 14, 2002.

Ignoring the local police chief’s repeated warnings, the villagers connected a towboat with the ship and were about to drag it to the harbor’s main channel when over 100 officers arrived to stop them. An intense clash and standoff resulted, and by evening the instigators were arrested and the ship dragged back to shore.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This was the first desperate measure of Hongmaogang Village Rights’ Promotion Association chief Chang Chi-hsiung (張吉鴻). If their situation remained unresolved, they would bomb an empty pier next, then a working pier and finally they would start targeting foreign merchant vessels to turn their plight into an international crisis.

The once-bustling, centuries-old fishing village had been marked for demolition since the 1980s, but their nightmare begin decades earlier.

The creation of Kaohsiung’s second harbor adjacent to the village in 1967 was the first blow. A year later, the area was included in the new Linhai Industrial Park (臨海工業區) zone, which prevented Hongmaogang residents from building new developments. Meanwhile, the surroundings became increasingly polluted due to numerous factories setting up in the area with no environmental controls. This not only affected their health, but also their livelihood. After many protests and lengthy negotiations, the two sides agreed to a relocation plan in 1998 — but things stalled again.

Photo courtesy of Taipower

Coupled with the fact that they had stopped receiving compensation from the nearby Dalin Power Plant (大林電廠), things finally boiled over. After the bomb threat, 800 residents marched to Kaohsiung City Hall on March 1 to demand answers.

The villagers were finally relocated in 2007, and today in Hongmaogang’s place is the Kaohsiung Intercontinental Container Terminal.

THE BEGINNING

Photo: CNA

Hongmaogang (“red head harbor”) was likely named for the Dutch, who were active in the area in the 1600s. It was well-known for its aquaculture and fishing during the Qing Dynasty, and Japanese records in 1935 show that 685 out of 756 households engaged in fishing activities. In 1962, it ranked 12th in the nation in fish production. However, the industry quickly went downhill with the rapid industrialization of the area.

Lin Miao-chuan (林妙娟) recalls in the study, “Kaohsiung Hongmaogang: Societal Changes in a Fishing Village” (高雄紅毛港: 一個漁業聚落的社會變遷) that it was a prosperous place when she stayed there with her grandmother as a child, and lavish, month-long Taiwanese opera performances were put on at the temple plazas during peak harvest season.

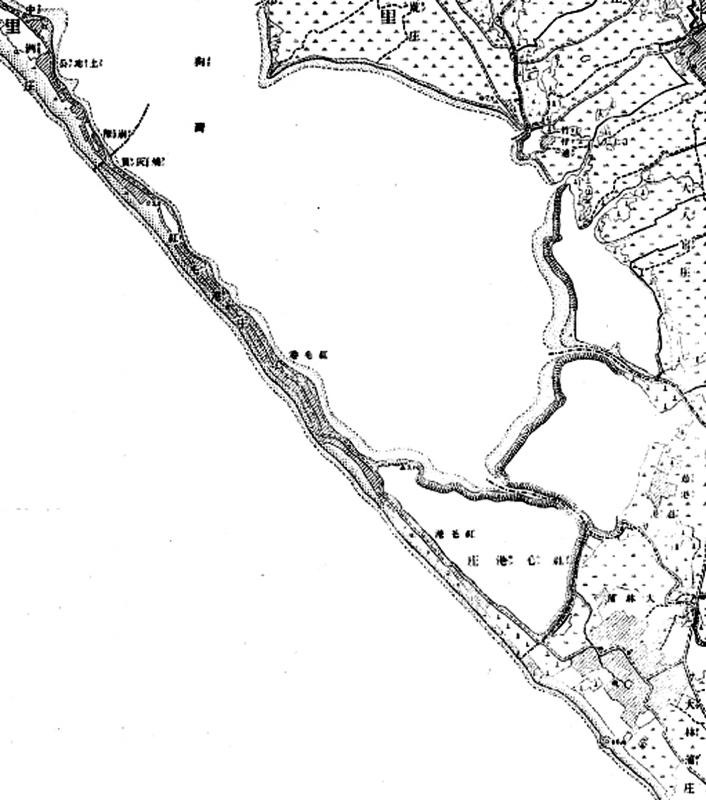

Hongmaogang was situated on a narrow sandbank connected to the main coast, and the locals likened the geography to a dragon. The construction of Kaohsiung’s second harbor in 1967 cut straight through the sandbank, turning Chijin (旗津) into an island while Hongmaogang remained with the mainland.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Locals believe that this cut the dragon in half, destroying the fengshui and altering the village’s fate forever. The harbor greatly changed the marine ecosystem, rendering many traditional techniques inefficient. The rapidly industrializing surroundings also seriously polluted the waters, further reducing the residents’ livelihood. Many turned to doing odd jobs or smuggling to survive. Others simply left.

A year later, the village was included in the Linhai Industrial Park, sparking the first discussions of relocation. The government restricted the villagers from development, but it could not make up its mind on what exactly to do with it over the next decade, causing Hongmaogang’s public infrastructure to lag behind other parts of Kaohsiung. To make matters worse, the Dalin Power Plant (大林電廠) was built atop the village’s fish farms.

FIGHTING BACK

Taipower did little to mitigate the plant’s environmental impact, and the residents suffered greatly from the coal ash and loud machine noises. The residents began protesting in 1988, and although the plant eventually agreed to compensate them monetarily for 10 years until the relocation was complete, they didn’t make any actual improvements until the mid 1990s. Since the move took more than 10 years to plan, this became the source of another future conflict.

The first government proposal to relocate the village was announced in 1985. The plan involved moving them to the Dalinpu and Fengbitou areas, but polls showed that while 99 percent of residents agreed to move, only 16.2 percent wanted to move to the designated area as it was unstable reclaimed land that was closer to even more factories.

How is this better? they justifiably asked.

The plan was adjusted in 1989 and again in 1992, but none of these plans worked due conflicts between residents and the government. The compensation and housing scheme also did not fit the needs of locals as their household registrations were complicated, with as many as 14 households living in one building.

The issue dragged on, and on May 17, 1996, more than 100 residents staged a military-style rally at the pier, swearing to blockade Kaohsiung’s second harbor if their wishes were not met. Talks fell through the next day, and at 8am on May 19, about 40 fishing boats appeared and clogged the port’s main channel for the entire day, not leaving until around 10pm after the officials promised to sort the matter out by the end of June.

Finally, a proposal that seemed to work was drafted in 1998, but this one was hampered by intergovernmental disagreements due to compensation issues, lack of land and insufficient funding. The residents had already given up their land, plus, the Dalin power plant’s payments had stopped as they had expected the village to be relocated by then.

Sick of waiting, the residents staged their bomb threat demonstration in 2002.

In 2005, the residents accepted a flexible plan where they could choose their preferences based on their qualifications, and the move was completed in 2007, ending this 40-year saga. Today, there’s a Hongmaogang Cultural Park near the original site that preserves their memory.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),