Dec 6 to Dec 12

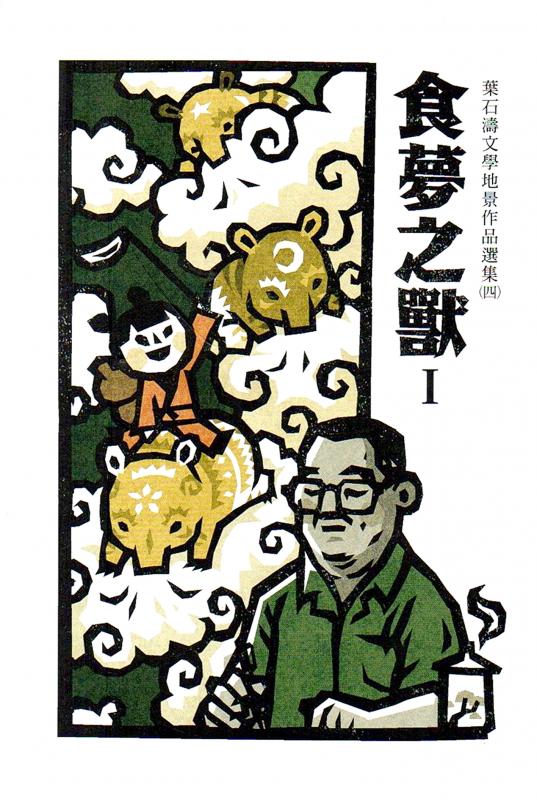

Yeh Shih-tao (葉石濤) once compared writers to beasts who devour dreams to sustain themselves. For the first 18 years of his life, Yeh’s well-off family could afford to let him daydream, and he shut out the world that was being ravaged by World War II, seeking refuge in the world of literature.

Despite a concerned teacher warning his father that the boy was “useless,” Yeh had penned three novels by the time he finished high school. His third attempt, A Letter from Lin (林君來的信), was modeled after the work of French novelist Alphonse Daudet and caught the eye of Literary Taiwan (文藝台灣) editor Mitsuru Nishikawa. Published in April 1943, it was Yeh’s official debut.

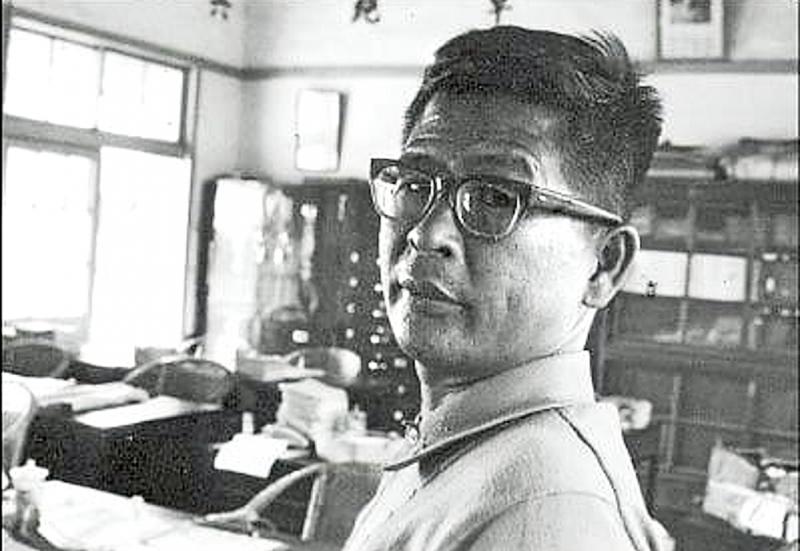

Photo: Liu Wan-chun, Taipei Times

The family’s fortune soon disappeared, however, and the young novelist was forced to confront reality. Not only did he struggle to make a living, he was no longer allowed to write in his native Japanese after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took control of Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War and fleeing China. The lowest point came when he was thrown in jail in 1951 for “failing to report a communist bandit,” a common charge during the White Terror.

Yeh was released after three years, and continued working as a schoolteacher. He got married and had children, so there was little time to devour dreams.

“How would he have known that a dream-eater also needs bread to survive? And this bread cannot be obtained by just dreaming all day,” he writes in his 1983 essay collection, A Literary Memoir (文學回憶錄).

Photo courtesy of Literary Taiwan Foundation

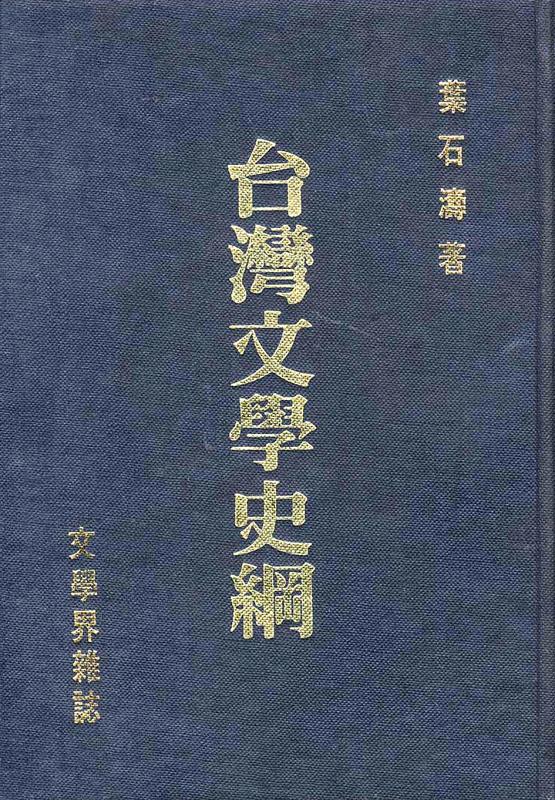

Yeh’s financial situation eventually improved, and in 1965 he wrote Youth (青春), which he calls his first serious work since the war. Yeh never stopped writing after that. Besides his powerful novels depicting the life of ordinary Taiwanese, he was also a prolific literary critic and historian, his best-known work being the 1987 History of Taiwanese Literature (台灣文學史綱).

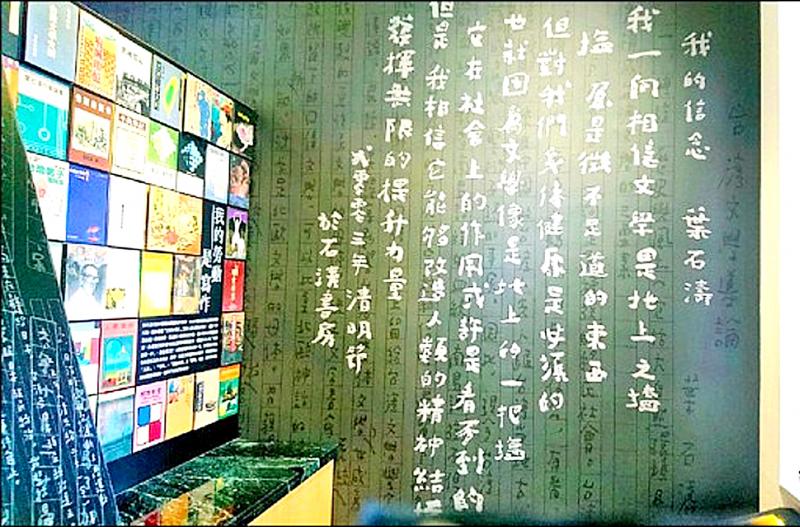

“My writing is my labor,” Yeh would later say, and by the time he died on Dec. 11, 2008, he had published more than 100 books and written more than 150 stories. Since the bulk of his tales included landmarks from his hometown of Tainan, there are several books that bring readers on tour of the city through Yeh’s prose.

EARLY AWAKENING

Photo courtesy of books.com

Taiwanese literature was at a high point when Yeh was growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, and he quickly became enamored with it from a young age. Even as the war broke out and life became difficult, Yeh spent almost all of his free time at the library and ignoring his studies.

At school, he was active in the archeology club, where adviser and shell expert Sueo Kaneko took them on frequent field trips where they unearthed numerous artifacts. Yeh recalls that this experience taught him to observe his surroundings and the rapidly changing society.

Yeh met Nishikawa at a literary conference in Tainan, and the two agreed that if Yeh could not continue his studies, he should move to Taipei and work for Literary Taiwan. Yeh had no confidence in passing the college exams, and his mother didn’t want him to go to Japan due to the war — especially after some of his classmates died in Allied bombings en route. So, upon graduation, he packed his bags and headed north.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While Nishikawa was raised in Taiwan, he belonged to the upper class. And although he was highly interested in Taiwanese literature, Yeh felt that his mentor could only see it from a colonizer’s perspective. Yeh’s ideas further changed after meeting future literary legends such as Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) and Yang Kui (楊逵), and he left Literary Taiwan after 15 months.

Yeh was later drafted into the Japanese Army, and, after Japan surrendered, his commander offered him a few unregistered army trucks and suggested he start a transport business. Yeh declined, stating that he wanted to write.

“Hey, you’re Chinese now, as a Chinese, how can you be writing Japanese novels?” Yeh recalls his commander saying. “You better give up on this dream. Go home and be a good person, maybe be an elementary school teacher.”

Photo courtesy of National Central LIbrary

The Yeh family had lost their ancestral home under the Japanese. Now, under new KMT policy, they also lost most of their land. Yeh became a teacher to make ends meet.

LITERARY HISTORIAN

Unlike some members of the “translingual generation,” Yeh eagerly took up learning vernacular Mandarin. He began by copying the Chinese novel Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢) word for word and adding his own commentary for better comprehension, and then reading others’ reviews and critiques.

By the time the KMT officially banned publishing in Japanese, Yeh had a decent grasp of Chinese. He was quite prolific during the late 1940s, but in 1951 he was imprisoned due to his friendship with former Taiwanese communist Chen Fu-hsing (陳福星).

After his release from prison, Yeh found it difficult to find work, and friends and family were afraid to be seen with him on the street. So he took a job as janitor. He was mortified when he ran into a former student: “Being a janitor does not fit with my life goals or abilities. Even if it’s just to make ends meet, I shouldn’t just take any job.”

Yeh went back to teaching and barely wrote for the next 10 years while raising a family. The launch of nativist publication Taiwan Literary Arts (台灣文藝) by Wu Cho-liu in 1964 inspired Yeh to pick up the pen again, as he hoped to contribute this renewed attention to Taiwanese culture. In 1968, at the age of 43, Yeh published his first book, Spring Dream at Gourd Alley (葫蘆巷春夢) and his first collection of literary criticism.

By 1985, Yeh felt like he had learned enough about Taiwanese literature to write a history of it.

“If Taiwanese want to claim their place in the world, we must have our own literary history, and we need to let others know about it as well,” he writes. “But back then, nobody did any research on it; there weren’t any sources or scholars.”

Years later, Yeh says that he had two regrets about the book’s contents: It didn’t include Aboriginal literature, and he also had to keep many sensitive issues vague since it was still the Martial Law era.

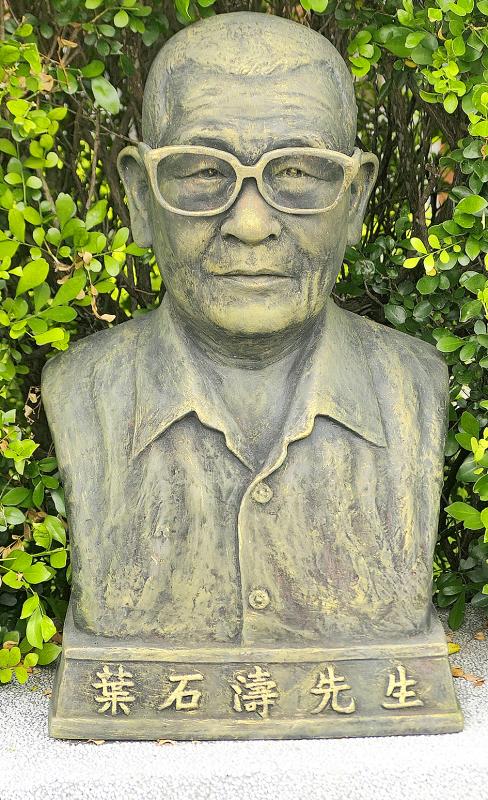

Yeh continued to write until his final years, and less than a year after his death the Yeh Shih-tao Literature Memorial Hall opened in Tainan. On Nov. 27, the museum reopened after extensive renovations and hosted the first Yeh Shih-tao Short Story Awards, which garnered 151 submissions. The judges could not decide on a winner, instead honoring six stories.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.