Nov. 29 to Dec. 5

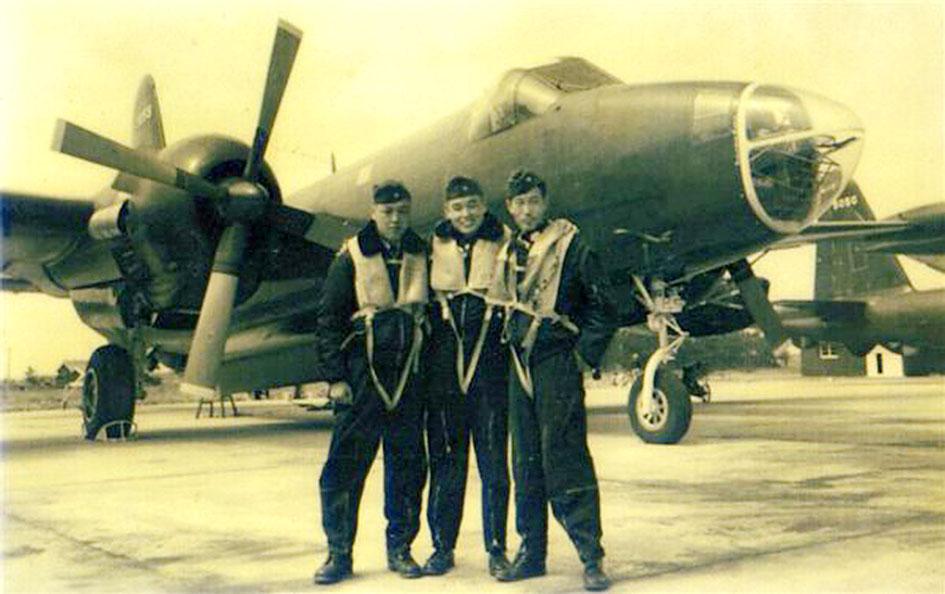

Every time Chu Chen (朱震) flew deep into enemy territory, he knew there was a good chance he wasn’t coming back. With two-thirds of the Black Bat Squadron — 148 members — perishing between 1953 and 1967, the odds were not on his side.

Chu had several brushes with death during his six years with the CIA-supported Bats, once surviving only because his Chinese attacker ran out of ammunition. But he pulled through each time and completed a total of 33 missions, the squadron’s second highest. He lived to the age of 86, receiving a presidential commendation after his death on Nov. 29, 2015.

Photo courtesy of Ministry of National Defense

Relatives of the deceased Bats tried for decades to find the remains of their loved ones in China and return them to Taiwan, but most of these attempts ended in failure. But there were successes, including the 14 crewmembers aboard a P2V-7U patrol aircraft captained by Chou Yi-li (周以栗), which was shot down over Jiangxi Province in June 1963. Through a chance encounter, their families found the crash site and, after cremating the remains, brought their ashes home on Dec. 4, 2001.

These efforts drew attention to the exploits of the Black Bat Squadron, which had remained largely unknown. Chu wept for his dead comrades during a commemorative event in 2012, telling the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper) that despite them taking on some of the most dangerous missions in the entire Republic of China (ROC) Army, many of their sacrifices were not acknowledged, and in some cases their families were never informed.

Former Black Bat Lu Te-chi (呂德琪) told the Liberty Times in 2007 that while they were more than willing to give their lives to protect the nation, former president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) promised them that the government would one day explain this top-secret program to the public.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“But after our missions were over, we still couldn’t drape the national flag over our dead comrades. We waited in despair, and eventually stopped talking about it. We thought that our stories would just be lost to the vicissitudes of history,” Lu said.

PERILOUS NIGHT FLIGHTS

It was not uncommon in the 1950s and 1960s for the ROC military to launch incursions into China, as president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) still clung on to his fading dream of retaking China. Anti-communist brigades infiltrated the Chinese coast, while fighter planes flew deeper inland to drop agents and gather intel.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These efforts were supported by the US, who wanted information on China as part of its international anti-communism efforts. Taiwan’s 34th Squadron was established with CIA support, and its job was to fly secret low-altitude reconnaissance flights over China.

All operations were carried out at night, hence the nickname Black Bat Squadron. It was led by Air Force Intelligence Administration head General I Fu-en (衣復恩), who, due to the project’s secrecy, reported directly to Chiang Ching-kuo.

“Since I oversaw the Air Force’s special ops projects, some people equate my name with these legendary [squadrons],” I writes in his autobiography. “But the real people writing history were the young heroes who penetrated deep into enemy territory … They borrowed time from God, and risked their lives year round — but the public had no idea of this.”

Photo: AP

I notes that each plane typically had 14 crew members, so “the loss of each plane meant the death of 14 comrades and 14 broken families.”

The 34th Squadron was officially organized in 1958, but it had already been carrying out activities with CIA support since 1953. I was placed in charge of the program in 1956, and for the first three years, each plane made it back to Taiwan safely. In 1959, however, a B-17 captained by Hsu Yin-kui (徐銀桂) was shot down by the enemy and crashed near Enping in Guangdong Province.

I’s most memorable incident was in 1960, when enemy planes got a lock on a P2V-7U flown by Tai Shu-ching (戴樹清) in Henan Province. Tai flew the plane toward a mountain and made a sharp right turn, causing the tailing enemy fighter to crash. Tai flew 78 missions during his career — the most of any Black Bat. He also died in 2015.

Photo: Su Fu-nan, Taipei Times

RETRIEVING THE BODIES

The Black Bats flew their last mission in either 1967 or 1968, and were disbanded in December 1974, near the end of the Vietnam War.

Newspaper journalist and editor Fu Yi-ping (傅依萍) was a child when her father died as a crewmember of the plane that was hit near Enping. Nobody knew anything about the Black Bats then; all she knew was that her father lost his life during a mission.

At the time, contact between Taiwan and China was not allowed, but people could ask friends and family in the US to contact the Chinese authorities to find out about their relatives in China.

For example, Meng Hsiao-po (孟笑波), the wife of Lee Hun (李睯), had been searching for his body for decades. In 1985, Lee’s brother, a US-based academic, obtained an official report about the incident from the Chinese.

After martial law was lifted, details from the report were published in a Taiwanese military magazine. Fu’s childhood neighbors happened to see the article, and sent it to her mother. Through the author, they got in contact with Lee’s brother, who told them Meng had been trying to visit China ever since the end of martial law to retrieve her husband’s remains.

Through three feature articles in the United Daily News, one of them penned by Fu, she was able to locate the relatives of 13 out of 14 crewmembers. A group of them flew to Enping in December 1992 and, with the help of local authorities, they spent hours digging up their remains, having them cremated in China and returning with their ashes to Taiwan.

Since the 14 bodies had been buried together for 33 years, the families opted to keep them together in Taiwan’s Air Force Cemetery. They were officially laid to rest on March 29, 1993.

The remains of those on Chou Yi-li’s plane followed a similar fate. In 1999, former Black Bat Kao Yin-sung (高蔭松), who had emigrated to Canada, saw a report about Chinese ace pilot and war hero Wang Wen-li (王文禮), who happened to be the one who shot down the plane. Kao noticed that the dates and details of an incident Wang described were eerily familiar. Kao reached out to Wang, who confirmed the crash and gave him the exact location where it took place. It had been 36 years, and the former enemies made their peace.

After much negotiation, Chou’s family headed to Jiangxi and retrieved what was left of the bodies and belongings. They were similarly interred in the Air Force Cemetery on Dec. 10, 2001.

Those who are interested in learning more about this part of history can visit the Black Bat Squadron Memorial Hall in Hsinchu City, which was opened in 2009.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of