Nov. 8 to Nov.14

A 10-year-old Chuang Ling (莊靈) recalls sleeping on top of one of the 772 large crates on the Chung Ting (中鼎號) warship as it made its way across the Taiwan Strait in December 1948.

About 320 of these boxes contained artifacts from the National Palace Museum in Nanjing. On the verge of losing the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) were trying to transport as many valuables as they could to Taiwan as part of their massive retreat. Two more shipments of national treasures would reach Keelung harbor in early 1949, making a total of 2,249 crates. The KMT were only able to retrieve about 20 percent of the museum’s collection, but these were carefully selected and the most valuable.

Photo: Yu Po-lin, Taipei Times

Chuang Ling’s father Chuang Yan (莊嚴) began working for the museum in 1925, and was in charge of the collection’s many moves over the decades to keep it out of enemy hands as war ravaged China. His family followed him wherever he went.

As the National Palace Museum did not reopen in Taipei until 1965, one can’t help but wonder what happened to these valuable artifacts during their first 16 years in Taiwan. It turns out that they were stored in a warehouse and cave near Beigou village (北溝) in Taichung’s Wufeng District (霧峰).

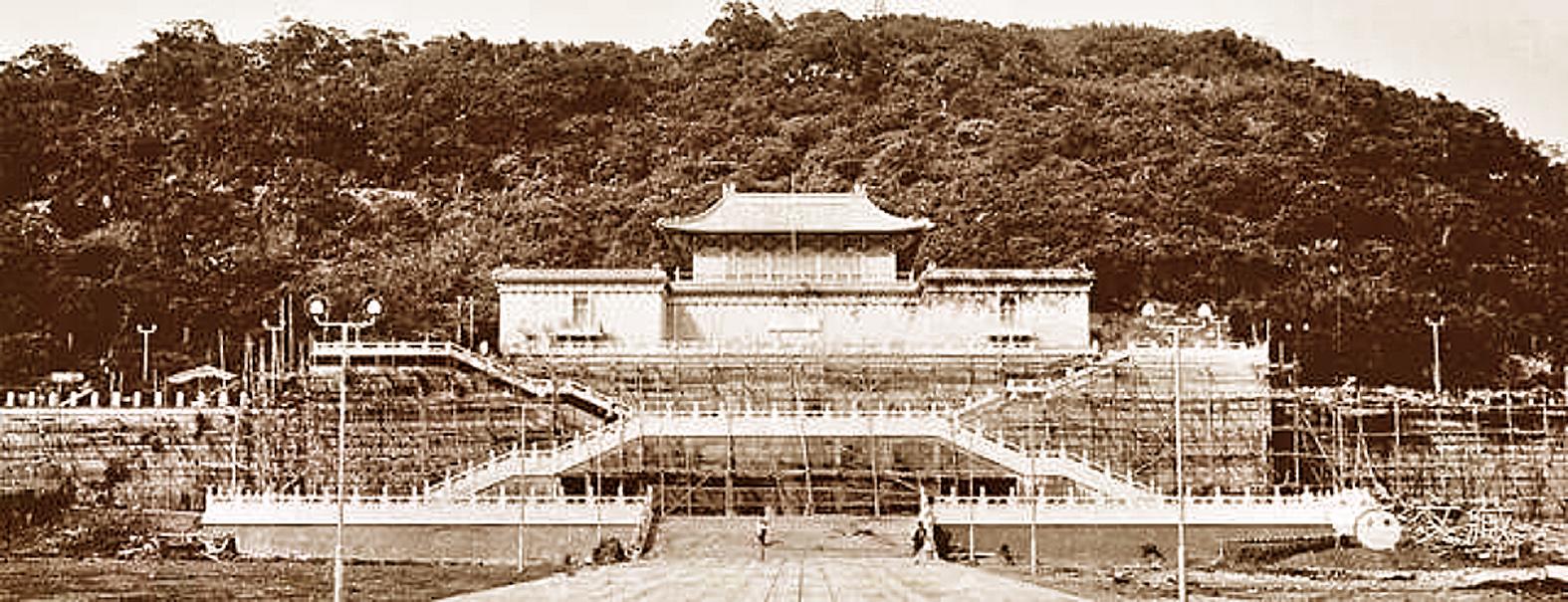

In 1956, a temporary display hall in Beigou was established, but it was too remote and small to draw visitors. Five years later, construction began on the current museum in Taipei, which opened its doors on Nov. 12, 1965.

Photo: Yu Po-lin, Taipei Times

FLEEING CHINA

On Oct. 23, 1924, the last Qing emperor Puyi was expelled from the Forbidden City. The next year, the National Palace Museum was established on its grounds, and a fresh out of college Chuang Yan was among many researchers who began working there.

Chuang oversaw the museum collection’s first move in 1933 from Beijing to Shanghai to keep them from falling into the hands of Japanese invaders. They were later moved to Nanjing, and then further west to Guizhou and Sichuan provinces as the conflict intensified. The treasures were shipped back to Nanjing after the Japanese surrendered, but then the Chinese Civil War broke out, leading to the decision to move them to Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These moves do not include shipping them to other countries such as the UK for display.

“I’ve been moving [these items] for half of my life,” he wrote in his essay series, Stories from the Mountain Hall (山堂清話). “I don’t dare call myself a ‘moving expert,’ but I think I’m close. It’s hard to think that this is not a predetermined fate from my past life.”

The decision to move the artifacts to Taiwan was made on Nov. 10, 1948, four days after the Chinese Communist Party launched a major offensive against the KMT’s Xuzhou Command Headquarters. Selected books from the National Central Library and antiques belonging to Academia Sinica would also be moved.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first shipment was brought to a storage room next to Yangmei train station in today’s Taoyuan City. The officials later moved them to a disused Taisugar warehouse in Taichung due to the area’s drier climate.

This warehouse was later deemed too close to the city and other institutions that would be targeted during an air strike. Museum officials finally settled on a piece of land at the foothills near Beigou Village, and again Chuang moved his family to the area. The national treasures arrived in April 1950.

FINAL HOME

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

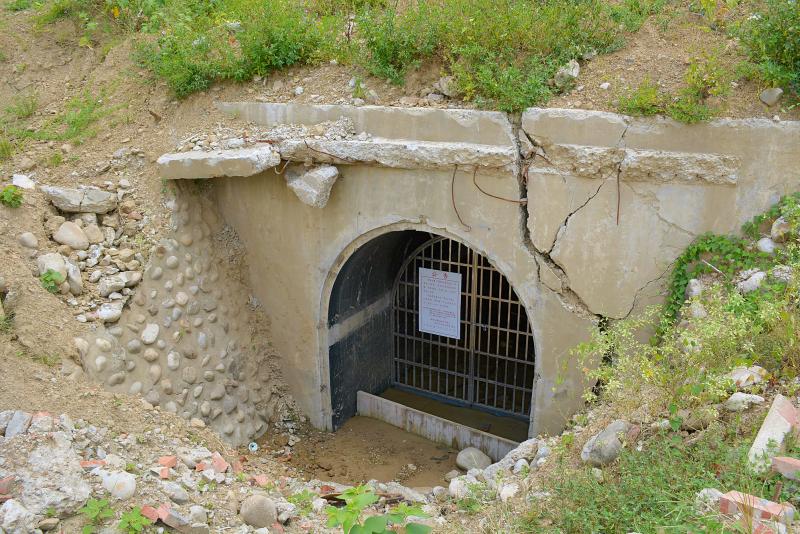

In 1952, work began on a 100m deep, 2.5m wide cave to further protect the artifacts in case of emergency. A few items were placed there, but ultimately it wasn’t suited for long-term storage. However, it was used several times, for example during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1958.

One of the first tasks was cataloguing the treasures, a process that took four years to complete. Both domestic and international requests to exhibit the items were growing, and at first the staff laid out the items on wooden boards covered with white cloth, and placed them in the aisles of the storage rooms. It was inconvenient and disappointing for visitors, and embarrassing for museum staff. In December 1956, a display room next to the warehouse was built.

This room could house about 200 artifacts, and the items were rotated every few months. It opened its doors in April 1957, drawing about 20,000 visitors in the first month. But due to the remoteness of the location, attendance gradually tapered off.

The highlight of this period was probably 1961, when 253 items were first displayed in Taipei to great fanfare, then shipped to the US for a special exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. They were then brought on a 10-month-long tour to other major cities, drawing a total of about 700,000 visitors, according to Taiwan Today. It was a massive hit among the public, with Life magazine devoting 17 pages to it.

Meanwhile, plans to move the artifacts to a proper museum were under way. Officials were initially divided on where to build it: Taipei was the obvious choice, but detractors thought the capital was too humid and unstable. Ultimately, Waishuangxi (外雙溪) was chosen not just for its scenery, but it was also the closest spot to Taipei where a tunnel could be built for emergency purposes.

Construction began in September 1961, and in October 1965, the national treasures embarked on yet another journey. As usual, Chuang — who was the museum’s deputy director by then — moved with the items.

“It’s been six years since the new museum building in Waishuangxi was completed,” Chuang wrote in 1971. “All the precious artifacts are displayed neatly or stored properly. The days of fleeing and storing them in caves and temples are long in the past. How many still remember that 40 years ago, there was a group of people hurriedly packing up each item in a dusty palace chamber?”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai