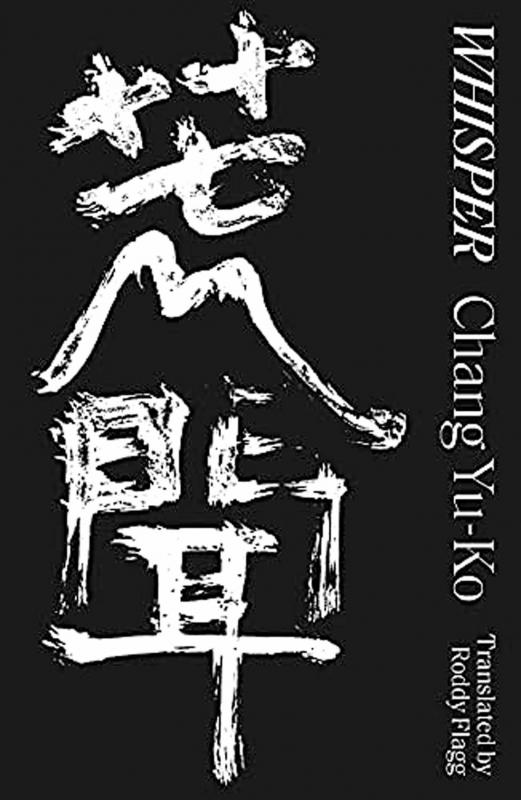

Whisper, a novel set in modern-day Taipei, opens with a middle-aged couple on distinctly bad terms with each other. The man is a taxi-driver and his wife works in a restaurant. Because of various heavy penalties imposed on them after some accidents at work they now live in a barely habitable shack. A daughter is absent, for no clear reason. The husband drinks and smokes heavily, while his wife endures yet another accident at work that’s likely to result in even more compensation payments.

In addition, each of them begins to experience what initially they take to be hallucinations. The man hears strange words coming from an old cassette recorder a passenger had left in the taxi parked next to his, while his wife dreams of a teenage girl without a proper face beckoning her in countryside that resembles Japan.

Bad becomes worse when the wife falls, or jumps, from a second-floor window and needs emergency surgery. But in the hospital she keeps repeating a name, Minako, the same word her husband had heard from the cassette recorder. Could this really be a coincidence, he wonders.

Plot developments now come thick and fast. Recovering from her operation, the wife becomes convinced that her daughter is in danger, then dies of a twisted neck. Meanwhile her husband picks up in his taxi, near Shin-Beitou, someone who appears to be a priestess who conveys what could be interpreted as the same warning.

In other words, what began as an exercise in dystopian social realism begins to turn into a ghost story.

It isn’t long before Minako — who, it transpires, is female — makes an appearance in the “real” world, or at least the world as the hospitalized wife understood it. The ensuing result is terrifying, as indeed it’s meant to be.

There’s a digression at this point. The wife had been transferred to a psychiatric ward after her complaints about hearing voices, and the only other person in the ward had been a Bunun Aboriginal girl, now inexplicably in shock. It turns out that she’d been a child prostitute, a fate common, a social worker insists, with Aboriginal children. This suggests some special knowledge on the author’s part — there are instances elsewhere, too, of detailed medical knowledge — and leads to an especially interesting few pages.

More details now emerge of hauntings and even deaths, both in Taiwan and in the former Japanese puppet-state of Manchuria where the husband’s father had gone to work in the 1930s. The Taiwanese instances appear to focus on Jade Mountain, an area held sacred by the Bunun people, and in the news following the anti-Japanese Wushe Incident of 1930 when the Japanese forcibly re-located the Bunun people to lower elevations (as described in Scott Ezell’s A Far Corner, reviewed in the Taipei Times on April 16, 2015).

Incantations, magical herbs, charms, protective inscriptions, the water in which a child has drowned — this book is increasingly characterized by the flotsam and jetsam of a Taiwanese spirit world. It’s even reminiscent of Macbeth in which occult agencies are everywhere active — something Shakespeare clearly associated with the Scotland of his day.

Gradually the threads are knitted together. Minako is revealed to be the name of a Japanese teenager who went missing on Jade Mountain in 1933, and the missing driver of the abandoned taxi that contained the cassette recorder is shown to have gone there and not returned. The taxi-driver husband, now a widower, decides, after a visit to the priestess he’d encountered earlier, to go to Jade Mountain to investigate.

Meanwhile a sub-plot follows the dead wife’s sister on the track of her husband, working in Beijing, and his suspected mistress there.

This novel cleverly links up details that have their origins in Taiwanese spirit beliefs with the details of modern Taipei life. There’s no question of spirits and ghosts only occupying spooky old buildings — they are living and well, we are led to believe, in every corner and intersection of the contemporary world. This is supported by the author’s familiarity with various brands of technology, from the mechanics of radio to Google Maps. What is extraordinary, however, is that Chang Yu-ko treats the ins and outs of spirit haunting with a very similar kind of familiarity, and perhaps even of belief.

The issue comes to the fore when the social worker who tended the Bunun girl in hospital decides to visit the Lele Hot Springs in the Jade Mountain region, along with her husband. She had researched the 1933 death of Minako in an old newspaper and argues for her haunting of the Bunun girl, despite her husband’s incredulity. Are spirits real or aren’t they? The author remains reticent, instead displaying a detailed topographical knowledge of both Lele Hot Springs and the whole Jade Mountain area.

As the different strands of the tale coalesce horror becomes piled on horror, together with a recurring sense of people being lost. But at the same time there’s an unavoidable feeling that everything’s being manipulated by an astute and educated mind, the author’s. As for this reader, I found myself reading the book faster and faster, unwilling to lay it aside until I’d discovered what was going to happen next, and how it would all end.

This novel isn’t as scary as Squid Game, but then nothing is. (Personally, I see Squid Game as an exercise in the different ways of killing people. Perhaps it should have been banned from the start).

Whisper ends abruptly with a run-down of what “really” happened to set up things as they appear to be in the ghost world. I found this confusing, while understanding the fix the author had got herself into with her multiple narrative threads.

Nevertheless, Whisper is a professionally put together piece of ghost fiction, and recommended to all who like that kind of thing. The translation by Roddy Flagg, incidentally, reads excellently.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has