NOV. 1 to NOV. 7

Chiang Si-chang (姜思章) was just 14 years old when he was forcefully conscripted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and shoved onto a Taiwan-bound ship. He didn’t see his family again for 32 years until he smuggled himself back to China via Hong Kong.

Fortunately, his parents and siblings were still alive, but few other fellow veterans had the courage to make the illegal journey. Ho Wen-te (何文德), for example, joined the army at age 17 just to make ends meet. He had no clue that he would never see his parents again.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

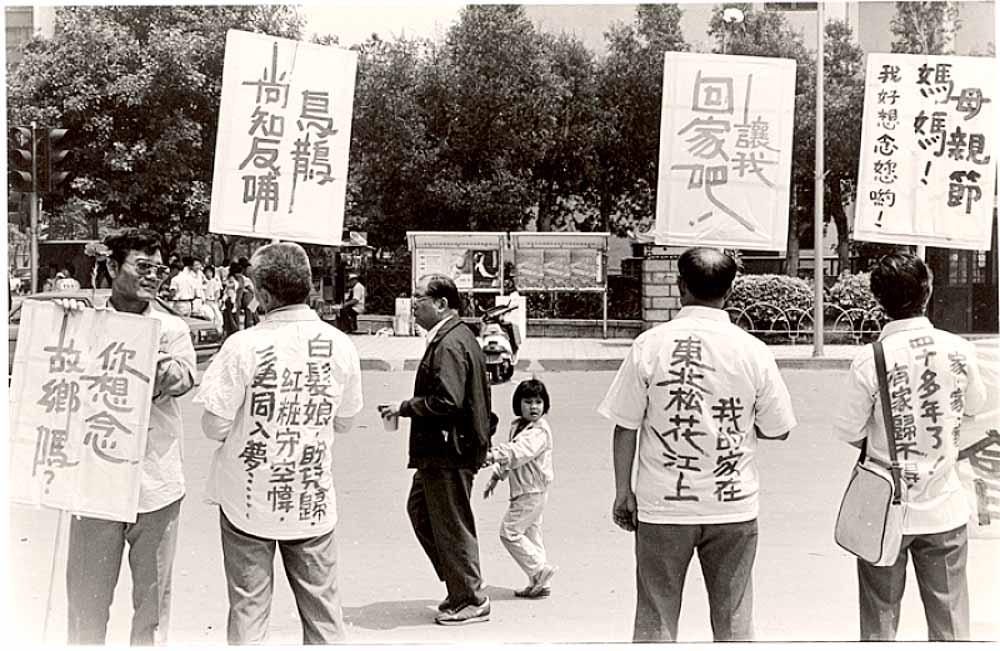

Ho, Chiang and other China-born veterans would later form the Mainlander Home Visit Promotion Association (外省人返鄉探親促進會), whose members took to the streets for the first time in April 1987 to hand out “Missing Home” flyers on the streets of Taipei.

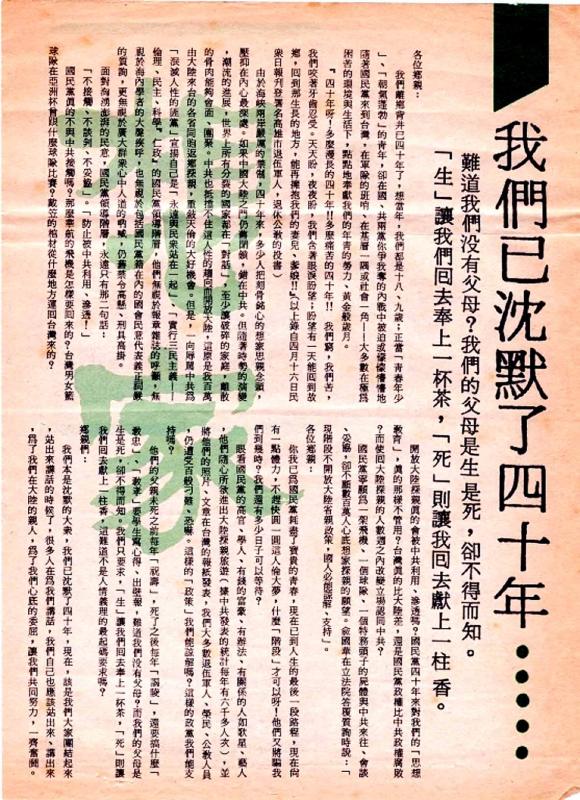

“We’ve remained silent for 40 years,” read the flyer, which was penned by Chiang. “Do we not have parents? We don’t even know if they’re still alive or not. If they’re alive, let us go home to serve them a cup of tea. If they’re dead, let us go home to burn a stick of incense for them.”

For nearly four decades, these soldiers were cut off from their loved ones due to the KMT’s strict no-contact policy with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But as the KMT loosened its iron grip in the 1980s, these soldiers — with the help of the newly-established Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) — decided to take a stand. There were KMT lawmakers who supported the cause too, but ultimately they couldn’t go against their own party’s policy.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Martial law was lifted on July 14, 1987, and in October, the government relented, allowing people to start applying on Nov. 2. The no-contact policy was still in place, so the Red Cross Society of the Republic of China handled the process through its counterparts in Hong Kong.

The rules stipulated that anyone, with the exception of active military personnel and public servants, were eligible if they had up to third-degree blood relatives or in-laws still living in China. The range was quite broad, from one’s parents or children (first degree blood relatives) to a spouse’s great-granddaughter-in-law (the spouse of a spouse’s third-degree blood relative).

Within six months, more than 140,000 people had signed up.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HOME BOUND MOVEMENT

Chiang’s situation was unlike most of the other soldiers who came to Taiwan in 1949, after the KMT lost the Chinese Civil War. He grew up in the Zhoushan Islands (舟山), which were still held by the KMT in 1950. There were as many as 150,000 troops stationed on the islands, but life went on as usual as Chiang prepared for his upcoming exams.

On May 13, 1950, he joined the ranks of one of more than 10,000 male islanders who were forcefully conscripted — many were around his age. After marching for two days, they reached the harbor where they were forced onto a boat bound for Taiwan.

Chiang lost all hope of seeing his family again until 1979, when the CCP offered to establish direct links with Taiwan. The KMT steadfastly refused and ignored Chiang’s petition to allow limited contact with loved ones, so he smuggled into China three years later.

The DPP made this issue one of its main priorities after its establishment in 1986. In addition to letting veterans visit China, the original proposal also sought to allow Taiwanese stranded in China or exiled overseas to return home, as well removing restrictions for Aborigines to freely enter their mountain homelands.

This was later narrowed down to the veterans homebound movement, where Chiang took more of a behind-the-scenes role due to his job as a schoolteacher, while Ho and others fought on the frontlines. Ho had found out a few years earlier that his parents had died, but it only strengthened his resolve to help his fellow veterans get home.

“Since there was no hope of retaking China, it was inevitable that the government would at some point have to let people visit their relatives,” wrote current Legislative Yuan speaker and then-Taiwan provincial consultative council member You Si-kun (游錫堃) in a 2017 article commemorating the 30th anniversary of the occasion.

The group staged its first rally on May 10 at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, wearing shirts with “Missing Home” painted on the front and classical poems expressing homesickness on the back. They held placards that read, “Mother, we miss you so much” and “You forced me to join the army, now let me go home.”

The movement gained widespread support, with KMT lawmakers such as Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康) also joining the cause. The government continued to refuse, noting that it was against national policy and could lead to CCP infiltration under the guise of peace and good relations.

UNFAMILIAR HOMELAND

By August, the KMT showed signs of relenting. On Oct. 15, it officially announced that people could start registering in November and visiting by December, and Ho made the trip in January. Its mission accomplished, the society disbanded a month later.

Around this time, several detailed “visiting relatives in China” guides appeared, which included maps, train timetables and tourist sites in a number of Chinese cities.

The guides urged visitors not to reveal anything about Taiwan’s military, government, economy, education and health system and even scientific discoveries. They also warned people to refrain from espousing any anti-Communist views in China, but most importantly refuse any offer to spy for the KMT, as that could lead to a death sentence by the CCP.

These guides, while extolling the sights and scenery in China with colorful photos, also made sure to paint the country as undeveloped and impoverished.

“Our homeland is our homeland, no matter how poor, backwards and painful the conditions are there, it’s still where were born, and where our ancestors are buried,” one book states.

As some visitors recalled, China’s landscape was still scarred by the disastrous policies of the 1958-1962 Great Leap Forward.

Due to travel restrictions, Ho flew to Hong Kong, then took the train to Guangzhou, then flew to Beijing via Xian before hopping on a train to Hubei Province’s Shiyan (十堰), where he hired a car to take him to his hometown.

His siblings greeted him at the family home entrance, and they hugged each other and cried. Ho was shocked by the gray hairs on his baby sister, who was just three years old when he left. He immediately headed to his parents’ graves and broke down in tears.

“Mom,” he said. “I’m home.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In 1990, Amy Chen (陳怡美) was beginning third grade in Calhoun County, Texas, as the youngest of six and the only one in her family of Taiwanese immigrants to be born in the US. She recalls, “my father gave me a stack of typed manuscript pages and a pen and asked me to find typos, missing punctuation, and extra spaces.” The manuscript was for an English-learning book to be sold in Taiwan. “I was copy editing as a child,” she says. Now a 42-year-old freelance writer in Santa Barbara, California, Amy Chen has only recently realized that her father, Chen Po-jung (陳伯榕), who

When nature calls, Masana Izawa has followed the same routine for more than 50 years: heading out to the woods in Japan, dropping his pants and doing as bears do. “We survive by eating other living things. But you can give faeces back to nature so that organisms in the soil can decompose them,” the 74-year-old said. “This means you are giving life back. What could be a more sublime act?” “Fundo-shi” (“poop-soil master”) Izawa is something of a celebrity in Japan, publishing books, delivering lectures and appearing in a documentary. People flock to his “Poopland” and centuries-old wooden “Fundo-an” (“poop-soil house”) in

For anyone on board the train looking out the window, it must have been a strange sight. The same foreigner stood outside waving at them four different times within ten minutes, three times on the left and once on the right, his face getting redder and sweatier each time. At this unique location, it’s actually possible to beat the train up the mountain on foot, though only with extreme effort. For the average hiker, the Dulishan Trail is still a great place to get some exercise and see the train — at least once — as it makes its way

Jan 13 to Jan 19 Yang Jen-huang (楊仁煌) recalls being slapped by his father when he asked about their Sakizaya heritage, telling him to never mention it otherwise they’ll be killed. “Only then did I start learning about the Karewan Incident,” he tells Mayaw Kilang in “The social culture and ethnic identification of the Sakizaya” (撒奇萊雅族的社會文化與民族認定). “Many of our elders are reluctant to call themselves Sakizaya, and are accustomed to living in Amis (Pangcah) society. Therefore, it’s up to the younger generation to push for official recognition, because there’s still a taboo with the older people.” Although the Sakizaya became Taiwan’s 13th