Hong Kong dissident artist Kacey Wong (黃國才) bounces around his spacious studio like a kid in a playground.

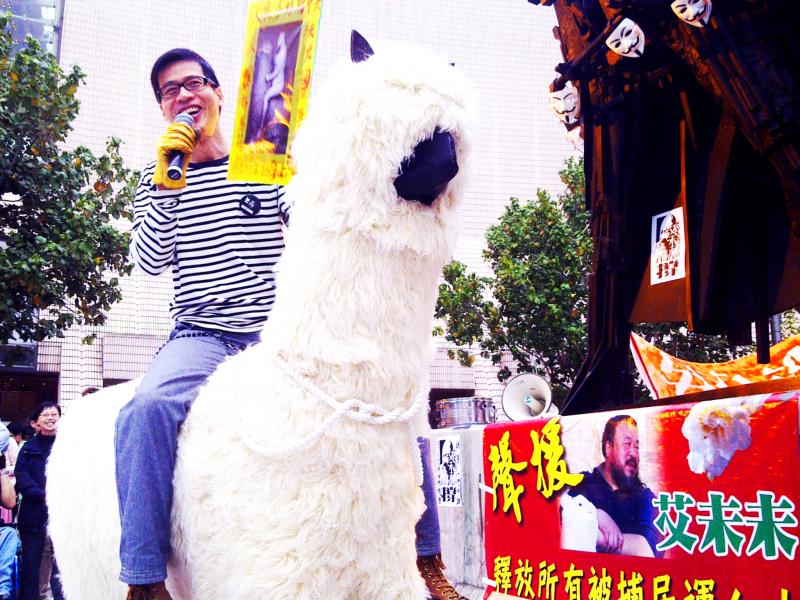

First to a towering cardboard robot, Attack of the Red Giant, which he pulled through the streets during Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement protests in 2014. Then on to the face drawing box used to draw the portraits of protestors the same year. And finally landing on the llama on wheels, created in 2011 after the arrest of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (艾未未).

“It says fuck you, but in a cute way,” Wong said, referring to his satirical artwork, born from the political unrest in the former British colony.

Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong

Fearing imminent arrest back in his native Hong Kong, the 51-year-old artist fled to Taiwan over the summer. With the recent crackdown on political protests, including mass arrests, he has no plans to return to Hong Kong any time soon.

It’s a self-imposed exile, Wong recently explained at his studio on the outskirts of downtown Taichung. Surrounded by fallow rice paddies, the studio houses his collection of sculptures and artwork dating back to the 1990s.

An accordion, tucked away at home, is one of the more sentimental favorites. In 2018, Wong used it to play China’s national anthem while inside a red mobile prison. Sarcastically dubbed The Patriot, the performance piece would assuredly land Wong in an actual prison if performed today. Fellow artist, Edmond Lu (呂志明), a longtime friend of Wong’s, said he hoped Wong would continue to produce artwork that challenges the political status quo.

Photo: John Evans

“[Kacey] said he will never return to Hong Kong,” Lu said in a phone message. Lu is also a former Hong Kong resident who moved to Taiwan several years ago, in part, to pursue artistic freedom.

Wong said he expects other artists and members of “the resistance” — as he calls fellow protesters — to flee Hong Kong for safer, more open-minded societies. Calling Taiwan’s diverse art scene active and refined, Wong said he’s looking forward to freely expressing himself as an artist and living in a functioning democratic society.

“The difference is shocking,” said Wong, juxtaposing Hong Kong’s and Taiwan’s two political systems. “[Taiwan] is what a democratically elected government should look like.”

Photo: John Evans

Wong said he looked at moving to England as well, but instead chose Taiwan for its familiar culture and proximity to his native Hong Kong, adding: “I want to walk around and blend in.”

While Taiwan is similar in many ways to Hong Kong, Wong notices differences too. For instance, Taiwanese are very polite, and then there are the little umbrellas for cell phones and jackets worn backwards while riding a scooter.

He likens himself to Humphrey Bogart’s character in Casablanca. Rick, the movie’s accidental hero, is forced to support the underground movement once conditions become unbearable.

Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong

“I don’t feel like I’m leaving Hong Kong,” said Wong. “I’m returning to an international world.”

POLITICALLY ACTIVE

Born in Hong Kong to parents he calls “politically obedient,” Wong grew up in a period of political freedom prior to the 1997 handover to China. Music from Japanese pop to English punk played from radios, and on the streets breakdancing was the new craze.

“I was a wild, rebellious kid,” said Wong, recalling his days BMX biking through the city and its neighboring hillsides.

In 1993 Wong got a degree in architectural design at Cornell University in rural upstate New York. A year later he returned to Hong Kong to be closer to his family.

His early artwork was less overtly political, focusing on societal issues such as housing and the environment. His piece Paddling Home mocked Hong Kong’s skyrocketing property prices. The floating 1.2 by 1.2 meter micro house featured amenities such as air conditioning and a TV. The price: HK$888,888.

In 2012, Wong took to the streets in his first overtly political artwork, a big pink tank, dubbed The Real Cultural Bureau. It was in protest of the creation of an office to oversee Hong Kong’s cultural affairs, such as museums, galleries and artwork in general. The officials in charge had close ties to the Chinese Communist Party.

Dressed as the director of the cultural bureau, Wong rode atop the cardboard tank handing out fake money as a way of lampooning what he saw as a corrupt political system.

Wong, who likes to describe his move to Taiwan as a period of self reflection, remains politically and artistically active. At last week’s Love for Freedom Calligraphy Art Festival in Taipei, he spoke on the importance of freedom of expression as an artist. On display was his piece, Cocktail Series, a collection of faux Molotov cocktails encased in resin.

And in March, Wong plans on unveiling new artwork at an exhibition in Tainan. The pieces will still be satirical and will certainly retain a political edge, he assured.

Artistic inspiration, Wong explained, doesn’t rely on physical surroundings.

“For me it doesn’t matter where I am,” he said. “But if I stay in Hong Kong, my fate in already written.”

For years Wong had seen friends and fellow artists arrested or detained by police, who he compares to thugs and gangsters. The arrests earlier this year of 53 people, including pro-democracy leaders and former politicians, under a controversial national security law, proved too much.

“That fear [of being arrested] is overwhelming,” said Wong. “You never know if the police will bust down your door at 5am.”

Had he stayed, Wong believes, he would have been arrested on charges of sedition and possibly tortured, followed by at least three years in jail.

This fear of intimidation and arrest still haunts Wong, which he likens to post-traumatic stress disorder. Occasional anxiety and bouts of anger rise up at unexpected times.

‘TODAY’S HONG KONG, TOMORROW’S TAIWAN’

One evening in August, Wong was exploring his new home of Taichung. Walking through a downtown underpass, he was surprised to see the walls lined with colorful notes, posters and drawings, all showing support for Hong Kong.

Known as Taichung’s Lennon Wall, the walls are plastered with sayings such as, “Stand with HK” and “Today’s Hong Kong, Tomorrow’s Taiwan.”

More shocking was when Wong saw a photo of himself. Clad all in black and waving a black flag in a 2019 protest march, Wong stands in the middle of a carless road in part of the occupied zone. Across the photo is written: “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our time.”

“The hair on my arms stood up,” he said. “I was touched but scared. It brings back all those old memories.”

Before leaving Hong Kong, Wong worked on his own neighborhood’s Lennon Wall, first erected in protest of police violence and political corruption. With fear of being snitched on by neighbors, Wong wore a wig to hide his identity as he hung posters late at night.

Protest walls of this type were once commonly seen in Hong Kong, said Wong. Nowadays, though, the posters on the walls have been taken down by authorities.

“The Hong Kong I knew no longer exists,” he said. “It’s an empty shell.”

Now in Taichung, Wong leads a more peaceful life. He visits museums, practices meditation and takes in an occasional movie. He even continues to practice the accordion, taking weekly online lessons from his old teacher in Hong Kong.

For the time being, he’s in a period of self-discovery as an artist. It’s like being in an ephemeral dream, Wong explained, and everyone is made of ash.

“I don’t want to repeat myself,” said Wong, before quipping a new idea for his artwork: “Maybe I’ll do a tricycle with a missile launcher on the back because Taiwan is continually under threat.”

In announcing his move to Taiwan, Wong made a black and white video featuring Hong Kong’s iconic waterfront. The song We’ll Meet Again plays somberly throughout.

Sitting in his Taichung studio, surrounded by his artwork, Wong said he understood the reality and heartbreak of “saying goodbye even though you know won’t meet again.”

Then Wong turned more terse and said: “I didn’t lose Hong Kong. Hong Kong lost me.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual