Sept.13 to Sept.19

Fu Pei-mei (傅培梅) leafed through the telephone book and jotted down the address of every prestigious Taipei restaurant she could find. She then mailed out her request: “Seeking famous chefs to learn cooking from, high pay.”

A star student from a wealthy family in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Fu never bothered with cooking growing up. After fleeing her hometown at the age of 15 due to the Chinese Civil War, she eventually ended up in Taiwan, where she held a number of clerical jobs in Taipei. She enjoyed office work, especially since the company provided meals.

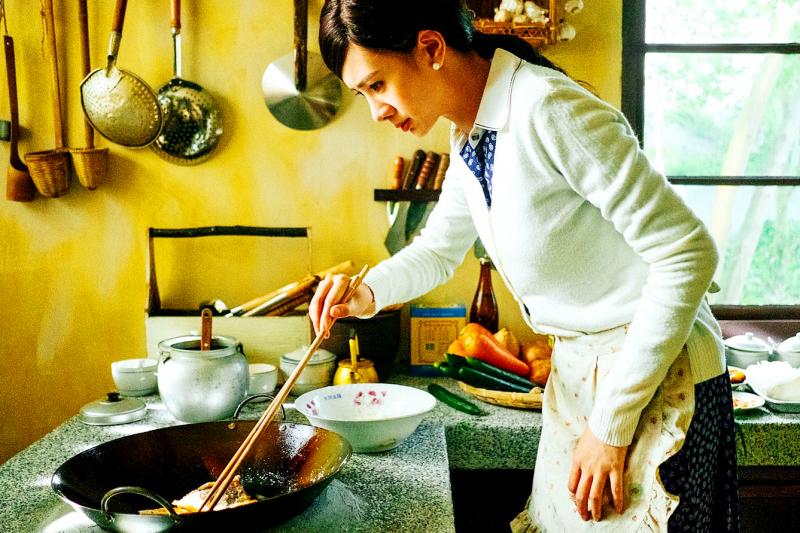

Photo: Wu Chih-wei, Taipei Times

This was the 1950s, however, and Fu soon left her job to marry fellow refugee Cheng Shao-ching (程紹慶), whom she was introduced to on a blind matchmaking date. She described Cheng as a reserved, patriarchal man.

“I was educated in a Japanese school where they taught us that women should be obedient, and I also watched my mother also dedicate her life to serving my father,” she writes in her autobiography, What She Put On The Table (五味八珍的歲月). “So I did not question a lot of the things that happened then. I never considered that perhaps the times were changing, and this mentality may no longer have been acceptable.”

Part of Fu’s duties as a housewife was cooking — but she barely knew how. She attempted to hone her craft several times, but never got around to it until her children were both in school. Cheng was having guests over more often, and it was customary for them to pay the host for food and drink. He criticized Fu’s cooking often, which drove the competitive Fu to seek help from the best.

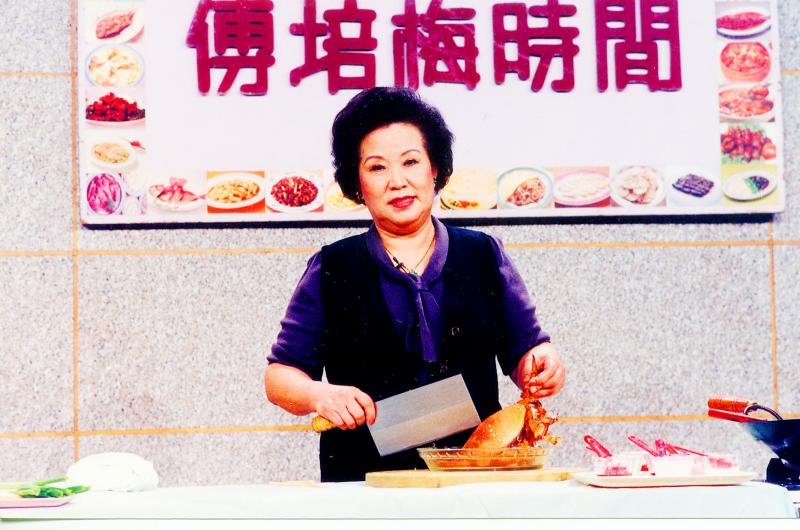

Photo: Chen You-ying, Taipei Times

Several chefs responded to Fu’s message. She learned quickly, and eventually became one of the nation’s most celebrated chefs. In March 1997, she won a Golden Bell Award for her beloved cooking show that was immensely popular in a rapidly modernizing Taiwan.

QUICK RISE

By 1961, Fu had become skilled enough to offer private lessons in the courtyard of her residence. Taiwan Television (台視), the nation’s first terrestrial station, launched a year later, and was recruiting a host for the cooking segment on their Happy Family (幸福家庭) program. Fu had several well-connected students, and one of them got her a meeting with the producer. In December 1962, Fu went on live camera for the first time.

It was a disastrous experience, as Fu realized that she had forgotten her knife right before shooting. She rushed to the station cafeteria and grabbed one, but it was so dull it took her much effort and time to make simple cuts. She went way over her allotted time, and the camera cut off before she could say goodbye to the audience.

Fu thought she had blown it, but to her surprise, the station invited her back the following week after viewers praised her performance. This time, she nailed it with a highly-difficult braised sea cucumber dish.

Two years later, Fu was given her own weekly show, which she also produced. She explored both Western and Chinese cuisines, and invited American guests on special occasions to demonstrate how to roast turkey and make hamburgers.

Fu’s name reached the West after the release of her English-Chinese bilingual cookbook in 1969. She was compared to Julia Child for the first time in a 1971 article by New York Times reporter Raymond Sokolov, who noted that Fu introduced Chinese cooking to America like Child did with French cuisine.

In 1977, Fu appeared on a foreign program for the first time on Japan’s Fuji TV. Attending Japanese school until she was 15, Fu could still speak Japanese. The popular show went on for five years, won several local awards and earned Fu honorary residentship from the government. Over the years, she traveled extensively as part of the government’s early efforts to combat its international isolation through soft power initiatives.

Fu’s last show, Fu Pei-mei Time (傅培梅時間), debuted in 1986, which featured her making five minute-meals five days a week. It was the first time her name was included in the title of her show, and it spawned a cookbook series with the same name. It was stressful to have to perfect a meal in such a short time on live television, but Fu writes that it was immensely rewarding.

A PHENOMENON

Wang Yuan-ju (王源如) writes in the study, “The Fu Pei-mei phenomenon: economic and social changes in 1960s Taiwan” (傅培梅現象: 60年代台灣與社會變遷), that people were increasingly using electric kitchen appliances in the early 1960s to save time. It also became a status symbol in a growing economy, as everyone wanted to have the latest gadget, from electronic ovens to washing machines.

The time was right for Fu’s show, as Taiwan was in the early stages of industrialization and television ownership was on the rise. People also began to live in apartments with built-in kitchens. Many women were working in factories, and needed to cut down their food preparation time at home. Being unfamiliar with fridges, gas stoves and rice cookers, Fu taught them all they needed to know.

Her show was the first in the nation to employ step-by-step, quantified instructions using modern technology. Its ratings soared, leading to a proliferation of similar programs by rival channels.

“Fu was a beloved figure whose warm demeanor and expert lessons helped countless home cooks become more confident in the kitchen — and make delicious traditional meals too,” the description read when Google made Fu its doodle on Oct. 1, 2015 to mark what would be her 84th birthday.

The doodle called her a “leading authority on Chinese cooking” and features two her best known recipes: fried prawn slices with sour sauce (醋溜明蝦) and the Cheng Family meat dish (程家大肉).

Other industry endeavors include designing airplane meals for China Airlines and serving as technical advisor for instant noodle flavoring for Uni-President Enterprises Corp (統一企業).

Fu tried to retire in 1993 on the show’s 30th anniversary, but TTV begged her to stay for several more years. She authored over 50 cookbooks, presenting an estimated 4,000 distinct dishes. In 1998, she was listed among Commonwealth Magazine’s (天下) 200 most influential professionals in Taiwanese history. She died on Sept. 16, 2004.

The entry read: “In those tougher times, Fu Pei-mei always relieved our hunger and worries, and also encouraged us to pay more attention to what we ate and to enjoy life more. In those times of austerity, Fu Pei-mei warmed the stomachs of every Taiwanese.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades