For a few moments, I thought my day in Douliu (斗六) was going to turn trippy.

Yunlin County’s biggest (in fact, it’s only) city has a population of just 109,000. It certainly isn’t a place where psychedelic counterculture flourishes. A picture dictionary could use an image of Douliu to define the adjective “staid.”

This mind-bending experience, brief but utterly unexpected, came courtesy of a middle-aged man I’d met on the corner of Jhonghua Road (中華路) and Taiping Street (太平街).

Photo: Steven Crook

From the back of a blue truck, the kind of vehicle that’s as common as chopsticks in rural Taiwan, the man and his friend were dealing in garlic from Cihtong (莿桐), a township a few kilometers north of Douliu. The unwashed bulbs looked as if they’d just been pulled from the ground.

He broke open a raw bulb, used a grubby thumb to rub the dirt off a clove, then offered it to me. My mother and my teachers always told me to never accept snacks or drinks from people I don’t know. So naturally I put it in my mouth without hesitation, and began chewing.

“Very spicy, right?” the man said, grinning with unabashed joy as beads of sweat formed across my forehead. My eyes turned watery, and for a second or two I felt like I was swaying back and forth. But I continued to suck the now pulpy garlic. It was, for want of a better word, interesting.

Photo: Steven Crook

We chatted for a minute or two. I gave him answers that seemed to make him happy, and which also happened to be truthful. I’m from England, actually, not the US. No, not much garlic is grown there. And I’m sure no British garlic compares with this remarkably piquant allium.

As soon as I was around the corner and out of sight, I gulped down the contents of my water bottle. If there’d been anyplace where I could have sat down and regrouped, I would have.

Instead I pressed on. I didn’t want to miss any of Taiping Street’s deliciously ornate shop-houses. Most of the buildings that make this thoroughfare a must-see for architecture aficionados date from the mid and late-1920s.

Photo: Steven Crook

None appears to be identical to its neighbor. All have two floors, but some are better maintained — or have been more fortunate during earthquakes and typhoons — than others.

Baroque and neoclassicism are the strongest influences, but whoever designed numbers 134, 136 and 138 was clearly a fan of Art Deco.

The range of embellishments goes from birds to flowers to what look like micro-minarets. At the apex of their facades, several houses have surname crests. Among the family names I recognized were Chang (張), Chu (朱), Chuang (莊), Hsieh (謝), Kuo (郭), Lai (賴), Lee (李), Shen (沈) and Tsai (蔡).

Photo: Steven Crook

Number 51 lacks a surname, but bears the word “Chohatsu” in Latin script. I asked a native speaker of Japanese if they could tell me what this meant. They couldn’t. Was it the name of an enterprise during the 1895-1945 period of Japanese colonial rule?

Is that a rising sun on the front of number 47? And if it is, was it included to celebrate Japanese rule?

Numbers 63, 65 and 67 are among Taiping Street’s most colorful buildings, each being bedecked with what seem to be jiannian (剪黏, “cut and stick”) flowers and animals. This form of art — more usually seen on temple roofs — involves gluing ceramic shards in place to create three-dimensional decorations; these often look impressive from a few meters away, but a bit shoddy when you get close. The first floor of number 65 currently houses a claw-machine parlor.

Photo: Steven Crook

Hoping to get a bird’s-eye look at the old street, I infiltrated the upper levels of Central Mall (中央商場), a sleepy three-story business complex at the intersection with Jhonghua Road (中華路).

From there, I noticed that almost every house now has a metal roof. Originally, the roofs would have been tiled.

THE BEAUTY OF FUCIAN STREET

On a previous visit to Douliu, I’d not had time to explore Fucian Street (府前街), southeast of Taiping Street.

This part of Douliu is looking better than ever. The authorities have almost finished landscaping the canalized stream that Fucian Street crosses, and some intriguing structures nearby have been preserved.

The Memorial Assembly Hall (行啟記念館, 101 Fucian Street), completed around 1927, has a square porte-cochere. The interior is open from 1pm to 6pm, Wednesday to Friday, and from 9am to 6pm on weekends. However, there’s no need to plan your trip to Douliu around these times — the building’s elegant redbrick-and-concrete exterior is more engaging than anything inside.

A very short distance north of the assembly hall, partly hidden from the road by the adorable little house at 43 Fucian Street, I spotted a tumulus-like hillock topped by several rotating air vents.

The first entrance I spotted was sealed, but on the other side there was an open doorway, and inside the lights were on. As I’d suspected, it was a former air-raid shelter.

So the ex-shelter doesn’t flood during thunderstorms, the floor just inside the entrance slopes upward, before sloping down to below street level.

The structure — which doesn’t seem to be marked on any online maps — has been reinvented as a cultural property, but at the time of my visit it was empty save for some folding chairs and a stack of wooden window frames. The latter, I guess, had been salvaged from the adjacent police dormitory, much of which has already been demolished.

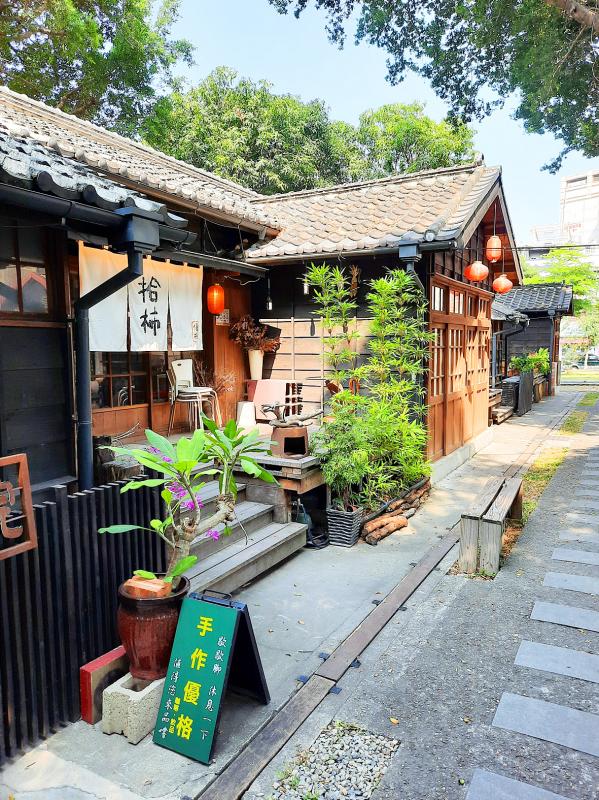

If you’re returning to Douliu Railway Station, it makes sense to detour to Yunjhong Street (雲中街), where there’s a cluster of colonial-era single-story dormitory buildings, not all of which have been restored.

There’s nothing here you won’t have seen elsewhere. One unit has been repurposed as a coffee shop. Another sells arty souvenirs. It’s very pleasant but unsurprising. Ideal if you’re coming down from a consciousness-altering garlic experience.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger